Seeing Ourselves: Write to Preserve, Edit to Protect

The first time I read a story that featured a Native American protagonist, I was a high school senior. It was a significant experience for me. As an Ojibwe teen, I hadn’t realized my absence in books until that moment. In Stranger with My Face by Lois Duncan, teen Laurie learns she was adopted as a baby and that she is Native American. I was excited and intrigued to dive into the mystery-thriller in which Laurie’s twin sister, Lia, reconnects with her via astral projection.

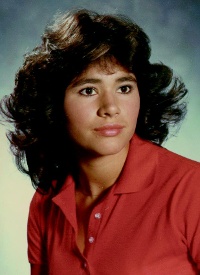

Angeline Boulley as a high school senior.

Photo courtesy of Angeline Boulley.

The first time I read a story that featured a Native American protagonist, I was a high school senior. It was a significant experience for me. As an Ojibwe teen, I hadn’t realized my absence in books until that moment. In Stranger with My Face by Lois Duncan, teen Laurie learns she was adopted as a baby and that she is Native American. I was excited and intrigued to dive into the mystery-thriller in which Laurie’s twin sister, Lia, reconnects with her via astral projection.

My excitement quickly subsided, to be replaced by something unfamiliar and uncomfortable. I didn’t have the words at the time to convey exactly why I felt so disappointed and, even, embarrassed. Now — as an adult with a twenty-year career striving to improve public education for and about Native Americans — I understand that the story lacked authentic representation and perpetuated stereotypes of Indigenous peoples.

Laurie’s adoptive father lovingly refers to her almond-shaped eyes as “alien eyes.” To me, alien means “not of this world.” Yet Laurie’s connections to “Turtle Island” (what many Indigenous people call North America) go back more generations than those of her adoptive parents.

Her adoptive mother explains they didn’t adopt her twin sister along with Laurie because of an inexplicable discomfort when holding Lia, who is later revealed to be malevolent. Stranger with My Face was first published in 1981, three years after the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) was passed to address the widespread removal of Native American children from their families and communities. Children who are enrolled members of — or eligible for enrollment in — a federally recognized Indian tribe are citizens of a sovereign nation. ICWA acknowledges the inherent right of an Indian tribe to its greatest resource: the citizens who will continue their nation. Under ICWA, there are procedures for keeping Indigenous children with their families, extended families, and tribal communities. The idea of splitting up twins because the adoptive mom had a bad feeling reads differently when you’re Native and know how many Indigenous children were cycled through the foster care and adoption systems.

As an author, I can understand using astral projection as a plot device. But I’m less comfortable with the easy explanation that the ability to project one’s spirit or soul into another plane of consciousness is an Indigenous thing; i.e., the “mystical and magical Native.” Not because I’ve never heard about astral projection through Ojibwe teachings but, rather, precisely because I have. The Shake Lodge teachings are not intended for those outside of those ceremonies. While each tribe has different expectations regarding the sharing of Indigenous knowledge — especially pertaining to ceremonial or sacred activities — the use of it as a plot device by a non-Native author writing Native characters remains a huge red flag. (Pun not intended but acknowledged, eh?)

Lia tells Laurie the tragic story of their birth mother, who had been married to the son of the tribal chief yet ran off with a white guy who dumped her after she became pregnant with the twins. Their heartbroken mother used astral projection to search for her lover. The “beautiful Indian maiden” stereotype perpetuates a white-gaze, curated definition of beauty that contributes to the sexualization and fetishizing of Indigenous women. The epidemic of missing and murdered Indigenous women (and girls and Two-Spirit individuals) began long before the creation of the #MMIW hashtag.

Writing a story featuring a character who is Native American is no easy feat. Land mines abound even for authors who are Native and writing from lived experience. I was guided by the mantra, “I write to preserve my Ojibwe culture; I edit to protect it.” I also felt that I should be able to explain my rationale to any citizen of my Tribe for any cultural knowledge I included in my story. Non-Native authors writing a story with a Native American protagonist do not have the same sense of accountability that one does when one’s identity is connected to an Indigenous community.

We Indigenous writers have always had the stories, though not the book deals. Thanks to efforts by We Need Diverse Books, the Kweli Color of Children’s Literature Conference, #DVpit, and others who advocate for writers from underrepresented communities, more Indigenous writers are now able to connect with agents, editors, critique partners, and support groups. These opportunities were crucial for me in strengthening my writing and pitching my manuscript.

My book deal changed my life. I am now a full-time author and public speaker advocating for Indigenous stories from Indigenous storytellers. Because every child and teen deserves to see themselves — and their communities — in the pages of a book, portrayed accurately and with sensitivity, depth, and nuance.

From the May/June 2023 special issue of The Horn Book Magazine: Diverse Books: Past, Present, and Future. Find more in the "Seeing Ourselves" series here.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!