Caren Stelson and Selina Alko Talk with Roger

The story of the Kindertransport is unusual among Holocaust narratives in that it has a happy ending — for a while. In Stars of the Night: The Courageous Children of the Czech Kindertransport, author Caren Stelson and illustrator Selina Alko explore the hope, heroes, and tragedy of the rescued children, a complex task for a picture book, as we discuss below.

Talks with Roger is a sponsored supplement to our free monthly e-newsletter, Notes from the Horn Book. To receive Notes, sign up here.

Sponsored by

The story of the Kindertransport is unusual among Holocaust narratives in that it has a happy ending — for a while. In Stars of the Night: The Courageous Children of the Czech Kindertransport, author Caren Stelson and illustrator Selina Alko explore the hope, heroes, and tragedy of the rescued children, a complex task for a picture book, as we discuss below.

Roger Sutton: Caren, you were going to tell me a story about your grandson.

Caren Stelson: I sent my son, Aaron, a package with some Hanukkah presents in it and slipped in a copy of Stars of the Night. I thought I had included a note saying, “Put this away for a few years before you read it to the kids.” But my grandson Reid, who’s five, saw the book and said, “Read this, Daddy.” Oh, boy. When I asked how it went, Aaron said Reid had lots of questions. But what moved Aaron most — he was practically in tears — was how affected Reid was by his daddy’s reaction to the book. My son usually doesn’t react that way, so I was really touched. There is something very important about that. Even if children don’t understand the fullness of a story, if their caregivers are reading it and absorbing the power of it, that experience will stay with children. I hope they return to the book, and keep returning to it, and will understand that emotional piece in its fullness when they’re ready.

Caren Stelson: I sent my son, Aaron, a package with some Hanukkah presents in it and slipped in a copy of Stars of the Night. I thought I had included a note saying, “Put this away for a few years before you read it to the kids.” But my grandson Reid, who’s five, saw the book and said, “Read this, Daddy.” Oh, boy. When I asked how it went, Aaron said Reid had lots of questions. But what moved Aaron most — he was practically in tears — was how affected Reid was by his daddy’s reaction to the book. My son usually doesn’t react that way, so I was really touched. There is something very important about that. Even if children don’t understand the fullness of a story, if their caregivers are reading it and absorbing the power of it, that experience will stay with children. I hope they return to the book, and keep returning to it, and will understand that emotional piece in its fullness when they’re ready.

Photo credit (author): Sarah Pierce Photography

Photo credit (illustrator): Good Job Photos

RS: I’m pretty hardened and was reading along with equanimity, but as the end came, and we learned about Nicholas Winton, I started tearing up.

CS: There’s such humanity in this story, both on the part of the children and on the part of Nicholas Winton. I can’t help thinking how this theme ripples through that time period on to today. We still have not resolved these very difficult issues, and it’s up to us to step forward.

RS: Selina, can you share with us how you reacted when you read the manuscript?

Selina Alko: I was deeply moved. I loved the text’s collective perspective; it put me right in those children’s shoes. Growing up Jewish and having lived in Israel for a couple of years, I was familiar with the Kindertransport, although I also knew it was not a well-known part of Holocaust history. As a person who makes children’s books, I thought, wow, this is such a powerful way to tell the story, from the kids’ perspective. That line attributed to the mother of one of the children — “Let the stars of the night and the sun of the day be the messenger of our thoughts and love” — was so deeply powerful, and I connected with the symbolism right away. Almost immediately, I could see how I would illustrate it.

RS: American elementary students are certainly learning about the Holocaust earlier than I did back in the 1960s; I’m guessing, Selina, because you’re younger, you probably had Holocaust education from an earlier age.

SA: Not in public school. I learned about it only through my Jewish world, in Hebrew school and from my Jewish community.

RS: Caren, when did you first start learning about the Holocaust? What did your family discuss?

CS: I don’t know if I can come up with a moment when I first heard about it. It was just part of our family. We have family members who were lost in the Holocaust. There were such silences after the war, among my grandparents and my other relatives. My father fought in World War II as a Jewish officer in the infantry. I feel like I was wrapped in World War II, growing up, because of the silence around it in my family. There’s a deep, heavy silence that kept bringing me back to wondering what really happened. Selina and I talked about this, that if we were in a different place and time, which train would we have been on?

RS: You include that scary detail of the last train. And then, of course, the even scarier revelation later, that most of the parents of these children didn’t survive. How do you address this in words and pictures, in a way for children that is informative and elicits empathy, but doesn’t terrify them?

CS: That’s always a concern when writing about dark times. We need to share history. We cannot forget. How do we share this darkness without having children just close the book because it’s too traumatic? How do we lean into the compassion? I think of Nicholas Winton, his compassion and his actions. He asked: how can we prepare ourselves to act and to step forward in the face of injustice? I hope that’s the conversation that happens when this book is opened in a classroom or on a couch.

RS: Selina, how about you?

SA: A lot of the books that I’ve illustrated over the years have dealt with heavy topics. I feel like kids can handle the truth if it’s presented in ways that soften the blow, with less realism and more metaphorical imagery. My style’s not hyper-realistic; it has a lot of play and whimsy. I use collage, and I build layers. I hope it’s an entry point for kids to connect with the humanity of the story. Even just by looking at the stars and realizing, oh, yeah, we all are part of this universe. Even if they’re safe, they’re reading this story in class and maybe thinking about their own family. Kids will eventually leave home and have to say goodbye to their parents at some point, so it can even be a metaphor for separation, which is important to learn. There are different ways to look at this topic. You can also focus on Nicholas Winton’s heroism and how he did what he did so quietly. Kids can understand that. Oh, this person did such a good thing. He didn’t even tell anyone. We can all do righteous acts if we choose to. We have a choice.

RS: It's interesting to me that you have a happy ending in the middle of the book. The kids are escaping from danger. You worry about them in the beginning because they’re getting on this train without their parents. They don’t know what’s happening. The journey itself is terrifying, but they make it to safety. So you get this “ah, thank goodness” moment in the middle. Which then of course is curtailed by reality later, when they come back to Czechoslovakia as older teenagers and their families aren’t there.

CS: Yes, there’s that sense of relief in the middle; you can take a breath before you enter the next, difficult part of the story. But in the last part, there is resilience in the children and hope that they can go on with their lives and find their paths for themselves, their children, and grandchildren. Selina’s stars on the cover, you feel that swirl of light, of the sun or the stars, and it’s the light that guides us. That’s part of the hope of the book.

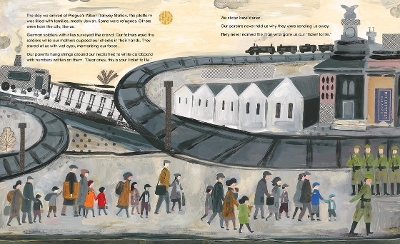

RS: The collage, Selina, sort of gets your fingers into the story as a reader. Because you touch the pages and think, oh, is this a photograph? Is this a quilt? What is this physical manifestation here? And you connect with it. How did you choose what kind of paper to use for the collage elements?

SA: When I was researching and doing sketches, I happened to be in Vancouver, where I’m from. My mother’s best friend’s family escaped from Germany, and she told me her story. I asked if I could look through some of her things. She had this German cookbook, and I Xeroxed some of the pages; in the coffeehouse scene at the beginning of the story, you can see some German words here and there from the recipes. For the train’s windows, I used the see-through part of window envelopes; I was randomly playing around in my sketchbook and came up with that idea. The other motif is the spiral notebook throughout, calling to mind the scrapbook found in Winton’s attic — and also the train tracks. Usually, I try to find some collage materials that relate to the subject matter, but I collect a lot of things as well, ephemera and so on, so there are also some random elements.

From Stars of the Night (c) Carolrhoda Books, an imprint of Lerner Publishing Group.

RS: Caren, would you say that your manuscript was essentially finished before Selina saw it, or did the two of you work together?

CS: The manuscript was really pretty stable by the time Selina received it, but we did do some exciting back-and-forth collaboration. When the art started coming in, I noticed that Selina had color-coded some of the children’s clothing so you could follow them from scene to scene. I thought to myself, I know exactly who those children are. I could name them. I shared that with Carol Hinz, our editor, and she must have told you, Selina, because you put their names in the scrapbook illustration. It was one example of how I knew we were connecting on this story.

RS: She got those kids from your words. Selina, what was it about the text that caused you to create the pictures the way you did?

SA: Even though Caren doesn’t mention any of them by name, I wanted to have some way to identify individual children throughout, so that the reader would have somewhere to look on every page to connect to specific kids. Caren piggybacked on that idea, and then we did a little back-and-forth.

CS: Those colors — orange, red, blues, and green — we can identify those children as they grow, and when we see their families. I just thought that was brilliant.

RS: One thing that amazes me about well-put-together picture books — and this definitely is one — written and illustrated by different people, is how the author has to leave room for the illustrator, and how the illustrator has to find those spaces in the manuscript to serve as her grounding, her inspiration. How does that work?

RS: One thing that amazes me about well-put-together picture books — and this definitely is one — written and illustrated by different people, is how the author has to leave room for the illustrator, and how the illustrator has to find those spaces in the manuscript to serve as her grounding, her inspiration. How does that work?

CS: I think there’s sort of a magic in all that. When I read the quote from Vera Gissing’s mother in Vera’s memoir — “There will be times when you feel lonely and homesick. Let the stars of the night and the sun of the day be the messenger of our thoughts and love” — I knew that was a line I would thread all the way through. I also could imagine, Selina, your picking up on that and we would weave the whole story together, visually and in words, around that beautiful message.

SA: It also takes a smart editor to do a pairing. I think you’re right, it is a certain kind of magic, and I was really honored and flattered when Carol sent me the story. The stars of the night motif was definitely something I could envision almost immediately. But it took a lot of sketching and reading the story over and over again, doing a bit of my own research and so on, to figure it all out.

RS: I think the metaphor about the stars in the sky is also something kids and parents can take from the book and make their own. You’re always separating, one or the other of you.

CS: Even though Selina and I hadn’t worked together before, we had both worked with Carol. We have developed such trust with previous projects that when we came together, it felt pretty seamless. The editor brings a lot of magic to it, too.

Sponsored by

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!