Race in fairy tales

There really are no valid excuses in my mind why more adaptations shouldn't be intentionally multiracial, particularly because fairy tales (by nature) have been proven to stand the test of time (and they're also required to be taught in school curricula across the country).

I grew up in the 1970s, when the lens on fairy tales turned academic and feminist. It was a time when fairy tales were being examined and critiqued for remaining wedded to their their antiquated gender roles--the recurring ideals of strength and adventure belonged to the realm of men and boys, and those of beauty and the need for rescue to women and girls. As a young feminist, this fresh and intelligent way of re-examining and interpreting old stories resonated with me, and I felt enlightened.

However, I was still drawn to fairy tales. Their epic themes of sorcery, betrayal, innocence, and revelry continued to capture my soul. I am easily enchanted by a talking mirror, a wolf in granny clothes with a dubious plan, eggs that beg “ Take me!”, etc. Threaded throughout the stories, too, were reassuring examples of redemption, loyalty, trust, and other virtues that I admire.

Eventually, I learned to read these stories more conscientiously when I was sharing them with students and, later, my own children, by highlighting female acts of bravery, ingenuity, and problem solving. I figured out how to tweak a line or two in the text that disrupted the gender stereotypes without actually altering the heart of the story. This made reading fairy tales something I could do in good conscience, mostly. What I could not adjust or tweak, however, was how overwhelmingly Caucasian fairy tales remained.

Most of the fairy tales embedded in the American vernacular are of European origin, and thus typically describe "European" features, hair, complexion, and landscape. In his versions of Rapunzel and Rumpelstiltskin, Paul O. Zelinsky includes medieval scenery and uses the illustrative, golden lighting seen in old Italian and French Renaissance paintings. I savor his books, and for me his technique works because it places the tales into the context of period pieces.

However, there really are no valid excuses in my mind why more adaptations shouldn't be intentionally multiracial, particularly because fairy tales (by nature) have been proven to stand the test of time (and they're also required to be taught in school curricula across the country). Over the years, several such fairy-tale adaptations have became favorites. Mufaro’s Beautiful Daughters by John Steptoe and The Talking Eggs by Robert D. San Souci and Jerry Pinkney both have smart, beautiful, and intelligent Black characters from cover to cover. Rachel Isadora’s Rapunzel and Hansel and Gretel are beloved to me. The Rough-Face Girl by Rafe Martin and David Shannon is often cited as an "Algonquin Cinderella." I love this story and the evocative illustrations that go with it; referencing it as a Native American version of Cinderella, though, seems Eurocentric. While there are similarities between the two tales, who is to say which came first?

By the time my daughter was born we had a stack of go-to tales that we read over and over again, curled up in our oversized, rose-covered armchair. When she was in kindergarten she asked me, “ Why are most of the people in my fairy tales white?” My daughter is biracial and identifies as Black. I was not surprised by her question, but stuck on how to address it thoughtfully. We decided that day that we had the power to change what we did not like. I told her that illustrators make decisions about what characters look like, and that we could be the masters of our own favorite stories.

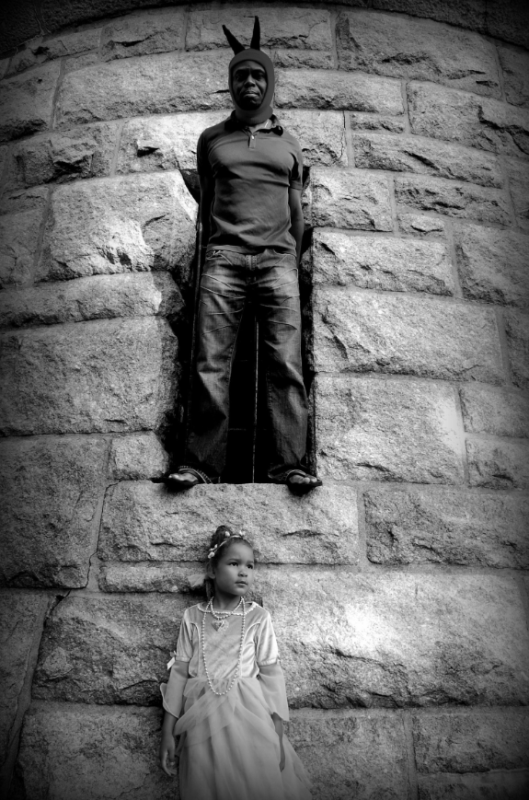

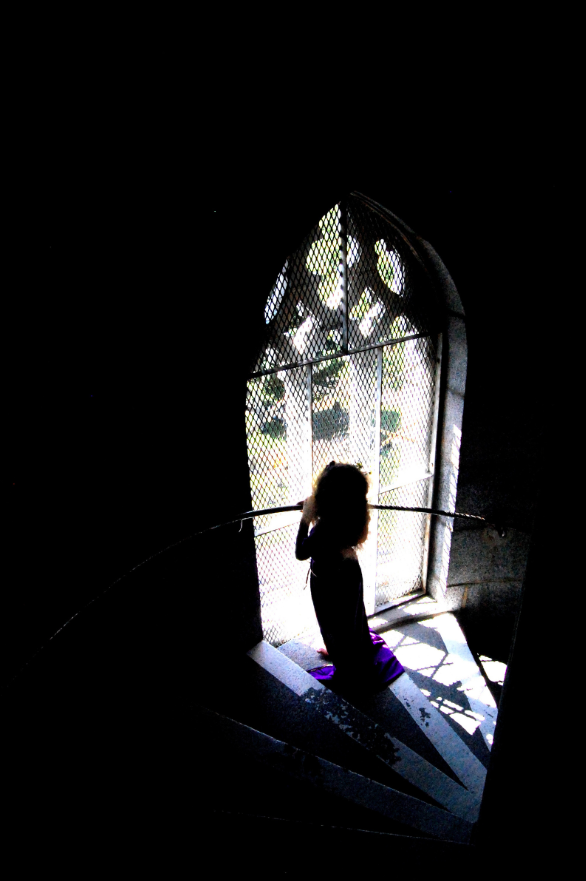

As a photographer, I had a tool to use in order to place my daughter directly into the stories as the main character. Over the next few months we collaborated on our own illustrative versions of several fairy tales. I intentionally used minimal props, as I hoped a balance of restraint and expression, so prevalent in these redolent tales, would come through naturally. A large piece of red felt, wildflowers picked beyond the walking path inside of Mt. Auburn Cemetery, an old hat that belonged to my son, and a Goodwill find or two were all we used. The most obvious prop was a spinning wheel, which believe it or not, I borrowed from my mother.

Doing this work together provided us space to have several deep and sometimes painful conversations about the lack of imagery of girls of color, particularly Black girls. I wanted to place her directly into the role of protagonist so that she would feel the enchantment of being center stage. Beauty is a commodity in fairy tales, and while I like to downplay that aspect of them, I do want her to know that beauty lives within the features of all ethnicities, and not only the Caucasian ones. Too frequently that is all she sees reflected back to her in children’s literature, media, and magazines. I never intended for this project to be a full body of work, or even to show it to anyone. I was just interested in showing my daughter that resistance could be beautiful and creative. Looking back at it now that she is older, I hope that it serves as both a talisman and a lasso, reminding her that she is protected by the magic inside of her and can harness the means to create change.

To see more of my Fairy Tale images or my two long-term projects that also deal with issues of visibility go to kristen-emack.format.com

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!

Kristen Joy Rmack

Thank you from the bottom of my heart Gail.Posted : Jun 13, 2018 11:35

Kristen Joy Emack

THANK YOU Elissa!Posted : Jun 10, 2018 12:22

Kristen Joy Emack

Thank you for your meaningful comment Shirley. Means a lot.Posted : Jun 10, 2018 12:21

Gail Mulcahey

You have been a fantastic mother since the day Niko was born. Your children mirror your kindness, love, drive and spirit.Posted : Jun 09, 2018 11:14

Elissa Gershowitz

Shirley + Kristen, you are both such wonderful inspiration and provide so much support for all of our families.Posted : Jun 08, 2018 09:21