Say it in verse

Poetry can be a powerful way for people to express complex emotions, and that’s certainly the case in these four recent middle-grade verse novels about the timely subjects of COVID-19, structural racism, the plight of refugees, women’s health and education, and mental illness.

Poetry can be a powerful way for people to express complex emotions, and that’s certainly the case in these four recent middle-grade verse novels about the timely subjects of COVID-19, structural racism, the plight of refugees, women’s health and education, and mental illness. See also our Five Questions interview with the New Yorker’s poetry editor Kevin Young about his picture-book debut Emile and the Field. During National Poetry Month in April, catch up with our reviews and click the tag Poetry.

Worst-Case Collin

Worst-Case Collin

by Rebecca Caprara

Middle School Charlesbridge 384 pp. g

9/21 978-1-62354-145-3 $17.99

e-book ed. 978-1-63289-922-4 $10.99

Ever since Collin’s mother died in a car accident, he has worked hard on instructions for what to do in a variety of disastrous situations. His orange notebook is filled with tips, such as these for surviving being buried in an avalanche: “Note where gravity carries your saliva. Dig in the opposite direction.” He misses his mother’s “morning smooch attacks” as well as the way she kept his brilliant mathematician father’s hoarding tendencies under control: “Without someone to keep / Dad’s collections in check, / layers accumulate / like…sedimentary rock formations.” As the condition of the house deteriorates, it becomes harder for Collin to keep himself clean and to find food. Fortunately, he has two close friends in Liam and Georgia, who don’t know about his father’s mental illness but are unfailingly supportive and help him feel normal. The verse novel pinpoints Collin’s grief over his mother’s death, his resulting anxiety, and how he copes with a father he loves but cannot rely on, using short, authentic phrases that home in on his feelings: “I can’t decide / if I should laugh / or barf.” The inclusion of several concrete poems adds impact, one of the most impressive being a poem in the shape of a house crammed to the brim with words. It’s a touching and believable story of getting through to the other side of a terrible time, with Collin’s practical survival advice sprinkled throughout. SUSAN DOVE LEMPKE

Samira Surfs

Samira Surfs

by Rukhsanna Guidroz; illus. by Fahmida Azim

Intermediate, Middle School Kokila/Penguin 416 pp. g

6/21 978-1-9848-1619-1 $17.99

e-book ed. 978-1-9848-1620-7 $10.99

“Water can trick us,” believes eleven-year-old Samira, recounting how the river had swallowed her grandparents as her family fled persecution in Burma. As unregistered Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh, mired in poverty, resented by locals, and under constant fear of deportation, Samira’s family lives in the shadows. Selling snacks on the beach to support her loved ones, Samira feels the acute loss of home, family, and community. As she befriends other girls like her, and they learn to surf in secret, her relationship to water changes from trepidation to exhilaration. When she decides to take part in a surfing competition, Samira must navigate stringent gender norms; happily, the girls band together to uplift one another. Interspersed with black-and-white sketches, the spare verse contrasts Samira’s carefree past and her present-day reality. Exploring fear and freedom in equal measure, the author presents a complex picture by relating the historical oppression and political exclusion of the Rohingya with Samira’s trauma and the challenges of resettlement. Samira’s ability to be both “grateful and angry” gives her a multifaceted personality that draws readers’ empathy. Samira’s story (one of few that highlight the plight of the Rohingya refugee community; see also the 2019 picture book The Unexpected Friend) is a testament to how inner courage and the spirit of sisterhood can help brave any storm. SADAF SIDDIQUE

Burying the Moon

Burying the Moon

by Andrée Poulin; illus. by Sonali Zohra

Intermediate, Middle School Groundwood 112 pp. g

10/21 978-1-77306-604-2 $19.99

e-book ed. 978-1-77306-603-5 $16.99

In this powerful verse novel, Latika loves school, but she knows that when she turns twelve she will be forced to quit. The reason? Toilets. In her rural Indian village there are no toilets; women and girls must relieve themselves in fields after dark to avoid “shame.” As she approaches puberty, she wants to “stop time / to stay a little girl” so she can continue her education without the complication of menstruation. When an engineer from the city installs a water pump for the village, Latika breaks the taboo and tells him about how the issue affects women’s health and girls’ access to education. Latika gives voice to something unspeakable and risks censure, but her bravery forces change and lasting improvement. She no longer wishes to “bury the moon” for the light it shines onto a supposedly shameful act but learns instead to view its light as friendly and useful. Emotive illustrations throughout employ deep, rich black and blue hues with bold accents in pinks and purples, accentuating the moonlight. Short poems allow for a powerful exploration of a variety of social issues, all linked to access to toilets and yoking together contradictory elements (fragile but strong; fearful but brave). An appended author’s note explains that toilet access is a global problem affecting over four billion people. JULIE HAKIM AZZAM

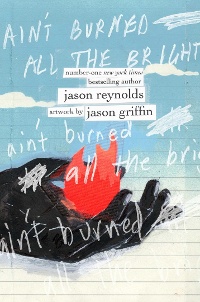

Ain’t Burned All the Bright

Ain’t Burned All the Bright

by Jason Reynolds; illus. by Jason Griffin

Middle School Dlouhy/Atheneum 384 pp. g

1/22 978-1-5344-3946-7 $19.99

e-book ed. 978-1-5344-3947-4 $10.99

Reynolds’s introspective narrative poem, with a young man at home during quarantine as its speaker, shares the stage with Griffin’s emotive collagelike illustrations done in Moleskine notebooks and reproduced on the pages to make it look like a real teen’s journal. The first-person text is presented in three parts, or “breaths.” In “Breath One,” the narrator says he’s “sitting here wondering why / my mother won’t change the channel // And why won’t the news change the story / And why the story won’t change into something new.” Along with concerns about the world outside, he thinks about his father coughing behind closed doors, his sister talking about protests, and his brother lost in video games. When the wonderings get to be too much, the narrator reminds himself to breathe “in through the nose // out through the mouth.” By the end of “Breath Three,” the narrator realizes that his “oxygen mask” for living through this uncertain time is the people he loves and the moments they share. The poem and images create an authentic-sounding adolescent narrator trying to grapple with the confusion and fear of the double pandemic (COVID-19 and systemic racism) he is facing. The book ends with a conversation between the two Jasons about their collaborative process for creating this work during the pandemic. NICHOLL DENICE MONTGOMERY

From the March 2022 issue of Notes from the Horn Book.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!