Profile of 2021 Newbery Medal winner Tae Keller

Tae Keller believes in the power of stories. In When You Trap a Tiger, she explores the stories that we tell ourselves — the ones that shape our identities. What are the stories we cling to and what are those we bottle up, never to see the light of day? How can we be sure that the world sees us — the full story?

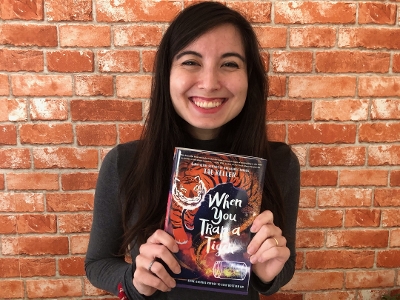

Tae Keller holding her "heart story." [Photo courtesy of Tae Keller.]

Tae Keller believes in the power of stories. In When You Trap a Tiger, she explores the stories that we tell ourselves — the ones that shape our identities. What are the stories we cling to and what are those we bottle up, never to see the light of day? How can we be sure that the world sees us — the full story?

Tae’s story began before she was born, when her grandmother and namesake, Tae Im Ku, moved with her three-year-old daughter, Nora Okja Keller, from Gimhae, Korea, to Honolulu, Hawaii. Her mother grew up to become a renowned author in her own right, winning an American Book Award for her debut novel, Comfort Woman. As a wordsmith herself, her mother recognized young Tae’s talent and took pains to nurture it. And at the Na’au writing school, Tae’s ability to dig deeper, to use imagery to create vivid emotions, continued to flourish.

At age eleven, Tae was featured in the Honolulu Star-Bulletin for her poetry. The newspaper printed Tae’s poem “Halmoni, I Wish You a Pendant” about loving and being loved by her grandmother. Here you will find the first sprinkle of stardust, the beginnings of the idea for When You Trap a Tiger.

I love the way

we turn the lights

low,

cuddle up at night,

tell stories of Korea,

your voice painting

pictures

of ghosts and tigers

in my mind.

Tae sent me the article when we began working on Tiger so that I could better understand her inspiration. In it, young Tae said, “Writing is a way to say how you feel without actually saying it when you’re talking. It’s yours, so you can say your emotions. It’s easier to use words on paper than saying something.” Here the reader glimpses a girl who labels herself as “shy.” A girl who knows she has something important to say and is trying to find the words. This eleven-year-old Tae would remind many readers of Lily, who often feels invisible until she makes a deal with a magical tiger to free her halmoni’s stories and finds her voice along the way.

How many kids have told themselves a similar story? That they are shy, invisible, loud, disruptive, nerdy, or stupid? When these insidious stories take hold, how easy is it to become defined by them — to continue to say “I am X” and never let go, never allow for change?

These are ambitious questions to tackle, but Tae’s writing always asks big questions. Her debut novel, The Science of Breakable Things, features a girl who uses the scientific method to “solve” her mother’s depression. I still sigh in admiration reading the last few lines: “As it turns out, you can’t always protect breakable things. Hearts and eggs will break, and everything changes, but you keep going anyway. Because science is asking questions. And living is not being afraid of the answer.” Tae wants her characters to live. In return, they jump off the page. Her middle-grade voice is like lightning in a bottle — rare and powerful.

But as everyone in publishing knows, second books are hard. Her debut received starred reviews and Best Books of the Year recognition, and we wanted her career’s narrative to be one that continued to build. So what would her next book be? The pressure was on.

In the summer of 2017, Tae asked me to meet her for lunch to discuss her new ideas. It was a beautiful day, so we sat outside at Serafina, a restaurant across Broadway from the Random House office, where you can spot the occasional celebrity but are more likely to run into publishing folks talking books. There, we discussed a few interesting concepts that will surely become future Tae Keller must-reads. But there was one that truly sparkled on that day. Tae sat forward in her chair — the opposite of shy — as she enthusiastically told me her idea for a story about three generations of Korean and Korean American women, who love each other but have stopped seeing each other. The idea sparked when she and her sister were making kimchi with their grandmother — a process that takes hours — and their halmoni filled the time telling stories about growing up in Korea. As the eldest, she had raised her younger brothers largely on her own. Tae and her sister had never heard these stories before. They had thought they knew all there was to know about their halmoni. Suddenly their grandmother was shining in a new light. What other stories from her past were still tucked away?

The “tiger book,” as we called it, was clearly Tae’s heart story. Researching the Korean folklore and history that give this book its depth would also allow Tae to share with the world another piece of herself. And it’s crucial to note that When You Trap a Tiger is not only the 2021 Newbery Medal winner but also the winner of the Asian/Pacific American Award for Literature. Tae did not set out to write a universal Korean American story but rather a deeply personal one, and in doing so she revealed the universal importance of telling someone, “I see you.”

When Tae delivered the first few chapters of the “tiger book,” the main characters were all there in their final forms. Lily, quiet and observant; Sam, angry and frustrated; and their mother, distracted and saddened by the impending mortality of her own mother. Any of the subsequent drafts could have gone to copyediting and been published, but Tae was always striving — she believed the book could be better. As Lily’s halmoni says, “When you believe, that is you being brave.” Tae’s writing is an expression of bravery. She has a natural gift for evocative imagery and voice, and also the courage to not rest on her prodigious talent. Anyone who has had the pleasure of following her on Instagram or receiving one of her fantastic newsletters knows that she is a student of craft.

In truth, she is an editor’s dream author. I considered it my job to simply ask questions. I knew she would always come back to me with an unexpectedly perfect answer. As I pulled on plot threads, she would weave them all back together with aplomb. Her skill at layering themes is nothing short of genius. (And I do not use that word lightly.)

With the powerful phrase “long, long ago, when tiger walked like man,” Tae created her own folklore — the star jar stories sprinkled throughout the book like magical fairy dust. In them, she was springboarding off of Korean folklore, her memories of her halmoni’s stories, and more modern tales. Savvy readers will recognize not just the echoes of “Little Red Riding Hood” but also If You Give a Mouse a Cookie, Goodnight Moon, and Where the Wild Things Are making subtle appearances. In When You Trap a Tiger, all stories are connected, just as all of the characters are craving connection. Joe, the gruff librarian, puts it best. “See, stories are like…water. Like rain. We can hold them tight, but they always slip through our fingers,” he says. “That can be scary. But remember that water gives us life. It connects continents. It connects people. And in quiet moments, when the water’s still, sometimes we can see our own reflection.”

In her writing, Tae has stilled the water, allowing us to see each other, and ourselves.

With this Newbery Medal, the world sees Tae Keller.

She is talented, fierce, and brilliant, and luckily for us, her story is only just beginning.

From the July/August 2021 issue of The Horn Book Magazine: Special Issue: ALA Awards. For more speeches, profiles, and articles, click the tag ALA 2021.

From the July/August 2021 issue of The Horn Book Magazine: Special Issue: ALA Awards. For more speeches, profiles, and articles, click the tag ALA 2021.

Single copies of this special issue are available for $15.00 including postage and may be ordered from:

Kristy South

Administrative Coordinator, The Horn Book

Phone 888-282-5852 | Fax 614-733-7269

ksouth@juniorlibraryguild.com

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!