An Interview with Ginny Moore Kruse

From 1938 until 1980, the same committee (in various iterations) chose both the Newbery and Caldecott awards. In 1979 the ALSC membership voted to establish separate committees — one for the Newbery and one for the Caldecott. Ginny Moore Kruse, director emerita of the Cooperative Children’s Book Center (CCBC) in Madison, Wisconsin, was a member of the last joint Newbery/Caldecott committee in 1980 and then chaired the first separate Newbery committee in 1981. I spoke with Ginny in early February 2022, over Zoom.

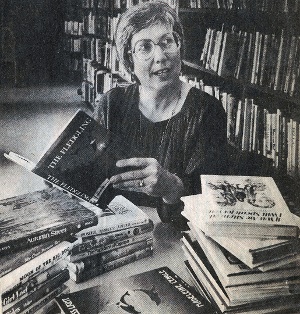

Ginny Moore Kruse in 1980, surrounded by some of the year's Newbery contenders.

Photo: L. Roger Turner for the Wisconsin State Journal.

NINA LINDSAY: Yours is quite a historic perspective! What are some of your memories of that final joint committee?

GINNY MOORE KRUSE: The 1980 Newbery/Caldecott committee chair, Barbara Moody, was wonderful. I remember her talking at the very beginning, when we were introducing ourselves, about the importance of the committee having “peacemakers,” and that we all had that role. We weren’t chosen to be peacemakers, but because we were there, we were expected to be. It wasn’t just up to her to keep the discussions going and to facilitate discussion and so forth, and that was important for me to hear.

NL: That’s such an collaborative way to call everyone to account.

GMK: The way Barbara managed our committee was that we would discuss, say, Newbery books for a while, and then we would have a short break, to stand up and move around. But our real break was then moving on to discuss the books nominated for the Caldecott. Different people who had disagreed with each other were allies now. It was so refreshing and community-building. Two committee members can strongly disagree with each other about most of the Newbery books, but then when they turn the discussion to Caldecott books, they find themselves agreeing more often than not, and previously established alliances shift. People weren’t always automatically in the same camp, as it were. That was extremely important and conducive to good discussions and relationships within the committee.

NL: You essentially got to work on different projects together as a team. With a different set of considerations.

GMK: Exactly. It was such a positive experience.

NL: By the way, how in the world did you and the other committee members manage to do the work of, essentially, two committees?

GMK: I always say that the work always fills the available time, whether you have five hours or fifteen. Also, you have to remember there weren’t as many eligible books being published in those days.

NL: What were some of the differences when you took over as chair the next year, for the separate Newbery committee? Were there advantages? Disadvantages?

GMK: One of the advantages of having separate committees is the obvious one: more ALSC members have the opportunity to serve on a major book award committee. More voices are heard. And that’s a big plus.

Another plus is that I wonder if the honor books have a larger role in the discussion of the separate Newbery committee and the separate Caldecott committee than perhaps they did when the same committee chooses both major awards and honor books. I don’t know whether or not my experience with that is simply my experience that year…but the honor books were very important in the year I chaired the Newbery committee. It gave people who might be disappointed in the outcome of the award decision another opportunity for every other book to be considered, and people had to pull themselves together from being disappointed or ecstatic because the remaining contenders were now competing with each other again. I think it’s a very exciting part of the process, because there’s certainly more than one distinguished book to bring to the public’s attention.

NL: What were some of the circumstances of that first Newbery committee?

GMK: It was such a different time then, in terms of technology and communication. Now, there are so many opportunities online for book discussions and interaction. I came from the CCBC, with its tradition of book discussions, so I had that advantage, but professional book discussion like that wasn’t common back then. Also, our in-person committee meetings were the first time many people were meeting each other, or even knowing anything about each other. So the committee dynamic was different then, we were starting from scratch, as it were. Also, in many instances the people who were on the Newbery and Caldecott committees were in positions where they were in charge of things, where people didn’t typically disagree with them.

Committee members also came from different fields. For instance, the Caldecott committee that year was chaired by Charlotte Huck, who had written a textbook on children’s literature and was a very prominent person in the field of education, not librarianship. So, we had a great variety of perspectives on the committee, but there was a definite difference in experience of evaluating and discussing books and in their comfort level in putting forward opinions.

NL: Knowing you were working with that dynamic, what did you do to facilitate discussion?

GMK: I tried to make sure that every voice was heard, as, in that setting, it could have been quite easy for some people to be intimidated by other members, and giving everyone a voice was really important to me. There were more barriers to equity among the committee members than I realized when I first went into it.

NL: Was it helpful for you and Charlotte to have each other as a partner to turn to who was dealing with some of the same issues?

GMK: Very much so. With the Newbery and Caldecott committees being newly separate, there wasn’t much history to rely on. I think we had a single sheet, each of us, with the terms of the Newbery, the terms of the Caldecott. And we had Bette Peltola’s 1979 Top of the News article, which described the history of the process for the committee. But we did not have a mentor or coach to turn to. After our committees made our choices, the winners had to be notified and the press releases written. Back then, only the chairs called the winners and honorees, not the whole committee. Mary Jane Anderson was ALSC’s executive director, and she said to Charlotte and me, after our committees had made our choices, “Just come to my hotel, and you can make your phone calls and work on your press releases in my hotel room.” So we did, and Mary Jane was on her way out the door, ready to go out to dinner! I can remember her putting on her fur coat and saying, “Have a nice evening, girls!”

So we ordered room service for dinner and got back to work. We were exhausted and just kind of grasping at straws. I can’t recall exactly how it went after that, but I do remember calling Katherine Paterson (the winner, for Jacob Have I Loved) and then the honor book people, Jane Langton (for The Fledgling) and Madeleine L’Engle (for A Ring of Endless Light). I remember those phone calls very distinctly. It was an honor and a pleasure to make them, and my exhaustion disappeared. I will say that it was a challenging experience to develop the press release without my committee. They were uncontrollable in their delight in having made the decision, they were ready to be done, and I had to just use nominations and my discussion notes and try to do my best on my own.

The actual press conference was different then, too. It didn’t happen for another day and a half, and in that time, the award results were leaked — everyone knew, it was kind of “wink wink.” It seemed as if we were just all pretending, and that never felt good to me. As I remember, the Newbery/Caldecott awards weren’t the big deal for ALA that they are now. Now they are really big in terms of the weight they’re given, the media attention. I mean, think of the press conferences now! The room is jammed with people. And not only ALSC awards, but all these awards — all this excellence. And all these excited people! It’s a big deal for ALA.

NL: It is a big deal. What other thoughts about the Newbery would you like to share?

GMK: It’s an exceptionally important award, and I am of the conviction that it’s a literary award, as opposed to a popularity award. I feel very strongly about having an award such as the Newbery in which the achievement of the winner is for that person’s outstanding achievement as a writer. If the book ends up being popular, then all the better. We have so many more discussion groups now than in the past, where people use the books with young readers to find out how they respond. I mean you have a whole range of possibilities for the Newbery. I’m very pleased that ALSC continues to have an award recognizing outstanding writing. It makes a big difference.

From the May/June 2022 special issue of The Horn Book Magazine: The Newbery Centennial.

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!