Welcome to the Horn Book's Family Reading blog, a place devoted to offering children's book recommendations and advice about the whats and whens and whos and hows of sharing books in the home. Find us on Twitter @HornBook and on Facebook at Facebook.com/TheHornBook

Treasuring when "nothing happens"

I admit I was immediately skeptical when I received a copy of the picture book Peanut Goes for the Gold by Jonathan Van Ness of Queer Eye fame, with illustrations by Gillian Reid. Though I’ve watched and enjoyed the show with my teenage daughters, I have a healthy suspicion of celebrity-penned children’s books.

I admit I was immediately skeptical when I received a copy of the picture book Peanut Goes for the Gold by Jonathan Van Ness of Queer Eye fame, with illustrations by Gillian Reid. Though I’ve watched and enjoyed the show with my teenage daughters, I have a healthy suspicion of celebrity-penned children’s books.

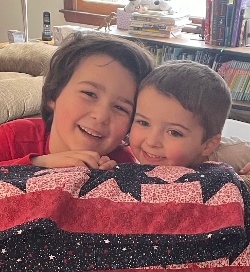

My leeriness was coupled with an outright weariness of anthropomorphic animals (Peanut is a guinea pig) and objects coded as queer, since picture-book publishing seems to prefer such characters to representations of actual queer people. So, when my youngest children, Jesse (5) and Zachary (3), found Peanut in a stack of books in my office and asked me to read it with them, they were decidedly more enthusiastic than I was. Nevertheless, I dutifully turned to my tried-and-true Whole Book Approach questions to begin our shared reading:

My leeriness was coupled with an outright weariness of anthropomorphic animals (Peanut is a guinea pig) and objects coded as queer, since picture-book publishing seems to prefer such characters to representations of actual queer people. So, when my youngest children, Jesse (5) and Zachary (3), found Peanut in a stack of books in my office and asked me to read it with them, they were decidedly more enthusiastic than I was. Nevertheless, I dutifully turned to my tried-and-true Whole Book Approach questions to begin our shared reading:

“Why do you think the endpapers are this color?” I asked, flipping between the yellow endpapers and the jacket art.

“Because it’s gold and the letters on the front are gold, too,” said Zachary.

“Because it’s gold and the letters on the front are gold, too,” said Zachary.

“Is Peanut a pirate?” asked Jesse.

“What do you see that makes you say that?” I responded.

“It’s not what I see,” he explained. “It’s those words ‘goes for the gold.’ Pirates love gold, you know.”

“Yeah,” said Zachary. “Gold treasure.”

“Oh!” I said. “Well, let’s find out if Peanut is a pirate.” We turned to the first page, and I read the first line of text: “‘Peanut has their own way of doing things.’”

“You mean his own way,” Jesse immediately corrected me.

“No, the words say, ‘their own way,’” I told him. “What do you see that makes you say his?”

“I thought the blue shirt,” he replied, revealing how he has been socialized in our cultural context to read the color blue as a visual code for the masculine. Then he added, “But look at the shoes!”

“Those are for shes,” said Zachary, and Jesse nodded.

In the illustration we were looking at, Peanut sports a pair of red high-heeled shoes. They aren’t as high as the shoes Van Ness often wears on Queer Eye, but they are definitely pumps, not flats.

“What do you see about those shoes that makes you think I should say she or her when I read about Peanut?” I asked.

“Those shoes are clicky like you sometimes wear, and you’re a she,” said Jesse.

“Right,” I said. “But isn’t it okay if someone who isn’t a she wears clicky shoes?”

“I guess so,” said Jesse, while Zachary looked on dubiously.

“Well, I think it’s okay,” I told them. “And the book says, ‘Peanut has their own way of doing things,’ which means Peanut isn’t a boy or a girl. A word for that is nonbinary,” I explained. “So, instead of saying he or she or his or hers when we read about Peanut, we say they and theirs.”

“Oh!” said Jesse. “That’s so good for them!”

“Yes!” I said. “That is so good for them. And in real life, the only way to know if someone uses he or she or them or some other way to talk about themselves is to learn from them about what is right and to believe them when they tell you.”

“I believe Peanut,” said Jesse. “I believe them.”

As we continued reading, I appreciated how the text is so matter-of-fact in its use of the singular they. Not only does this approach normalize the pronoun usage, it holds space for readers to discuss values that uphold self-determination and resist false gender binaries. I could see Jesse and Zachary working hard to make sure they used the correct pronouns as we talked about Peanut, incorporating this aspect of human diversity into their emerging worldviews.

A few months later, I received the book, The Little Library by Margaret McNamara, illustrated by G. Brian Karas. As a longtime Little Free Library steward at my home, I was excited to share it with my kids. That excitement was reinforced when I realized that this book, too, features a nonbinary character who uses they/them pronouns. This time, that character is a human--a school librarian named Beck, to be precise. As in Van Ness’s picture book, the text is matter-of-fact in its use of the singular they, and this time, Jesse and Zachary were unfazed by hearing it read aloud.

A few months later, I received the book, The Little Library by Margaret McNamara, illustrated by G. Brian Karas. As a longtime Little Free Library steward at my home, I was excited to share it with my kids. That excitement was reinforced when I realized that this book, too, features a nonbinary character who uses they/them pronouns. This time, that character is a human--a school librarian named Beck, to be precise. As in Van Ness’s picture book, the text is matter-of-fact in its use of the singular they, and this time, Jesse and Zachary were unfazed by hearing it read aloud.

“Oh!” I said once I read a line using “they” to refer to Beck, “the librarian is nonbinary just like Peanut.”

“Yeah, we know,” said Jesse. (Translation: “Big whoop.”)

“Keep reading,” said Zachary.

So I did.

This moment with my kids made me recall Alex Gino’s Stonewall Award speech for their middle grade novel, George, about a transgender girl named Melissa. They delivered it in Orlando in 2016 shortly after the Pulse nightclub shooting, which left forty-nine people dead and fifty-three wounded, most of them queer and most Latinx. In the speech, Gino said,

I have this image that runs through my mind. It takes place ten, twenty, thirty years from now. A cisgender, heterosexual, heteronormative, dudey-dude-bro, football playing, fraternity faithful guy is walking down the street. I mean, Dude-Bro. Total stereotype. Drunk as drunk on PBR at 4 in the morning. And in the other direction, walking towards him, is someone he identifies as trans. And somewhere in his notions and connections of transness, is Melissa’s story. And he thinks of Melissa as a person, and he sees the person across the street, and that real, live, possibly-trans person makes it through the night. And nothing happens. Nothing happens.

It's too early to know if Jesse and Zachary will grow up to be “cisgender, heterosexual, dudey-dude-bro guy[s],” but at this point they seem comfortable with the masculine pronouns assigned them at birth. Thanks to books like those about Peanut and Librarian Beck, they also seem comfortable with the fact that not everyone fits into a tidy cisgender binary, which bodes well for their future real-life relationships and interactions with trans and nonbinary people.

No, Peanut wasn’t a pirate, but the conversation and growth that their story prompted is one I’ll always treasure for the “big whoop”/“nothing happens” attitude it inspired when they met Librarian Beck--and I can hardly wait for them to meet Melissa, too.

For more, click the tags Pride Month and trans/gender nonconforming.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!

Susan Ellingwood

You should be so proud!Posted : Jun 29, 2021 11:10