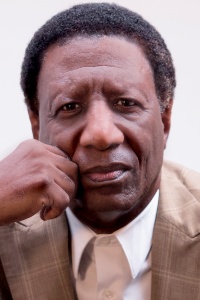

Wade Hudson Talks with Roger

With his wife Cheryl Willis Hudson, Wade Hudson founded the Black children’s publishing company Just Us Books in 1988. In Defiant: Growing Up in the Jim Crow South, Wade remembers his youth in 1950s small-town Louisiana, his academic and athletic achievements, and his initiation into a life of civil rights activism.

Talks with Roger is a sponsored supplement to our free monthly e-newsletter, Notes from the Horn Book. To receive Notes, sign up here.

Sponsored by

With his wife Cheryl Willis Hudson, Wade Hudson founded the Black children’s publishing company Just Us Books in 1988. In Defiant: Growing Up in the Jim Crow South, Wade remembers his youth in 1950s small-town Louisiana, his academic and athletic achievements, and his initiation into a life of civil rights activism.

Roger Sutton: I’ve got to say, Wade, one thing about your book is it felt to me like the town you grew up in, Mansfield, Louisiana, was almost a character all of its own.

Wade Hudson: That’s a good way to describe it, Roger. I never thought of it that way, but you’re absolutely right. I was hoping, as I was writing the book, to be able to capture what it was really like in that small town. And now I’m working on a contemporary novel that takes place in a similar small town, to show what life is like for a youngster growing up in a place like that today.

Wade Hudson: That’s a good way to describe it, Roger. I never thought of it that way, but you’re absolutely right. I was hoping, as I was writing the book, to be able to capture what it was really like in that small town. And now I’m working on a contemporary novel that takes place in a similar small town, to show what life is like for a youngster growing up in a place like that today.

RS: Have you been back to Mansfield?

WH: Yes, a few times. Two years ago, we gathered, my brothers and I. That was really great. I had not been to Mansfield for twelve years or so. My mother and father divorced in the late sixties, and my mother moved to New Jersey. She lived with my wife and I, and my sister who also lives here, for about thirty-five years of her life. We really didn’t have a reason to go back to Mansfield, because all the immediate family lived here — forty, fifty, extended family members. Mansfield has changed, and I shared some of the changes in the back of the book.

RS: I remember you said the demographics of the high school were completely switched.

WH: They built another high school, and another middle school and elementary school, in a different area of the parish, and those schools are predominantly white. Whereas the old white high school, Mansfield High School, is like eighty-eight percent Black. Mansfield Middle School is about eighty-nine percent Black, and it’s the same with the elementary school. It’s still segregated — not as it was back in those days when no Black students could go to the white school, but the communities are still segregated. The area of the city where I grew up is still pretty much a Black community.

RS: One perception that’s changed, at least for me — and obviously, I’m white — growing up, we thought integration was the be-all and end-all to solve all the racial problems in this country. And now people are questioning that. Was that the solution?

WH: There are pros and cons for both. There certainly have been a number of Black people who have taken advantage of opportunities that have come about from being part of an integrated society. And there are others who probably needed more of the nurturing and support that an all-Black community provided. It provided for me — I grew up in an all-Black world. My brother and I were just talking, before you called, and we’re amazed at how well so many of our classmates have fared with their lives, coming from a Jim Crow kind of world where we didn’t have the advantages or the resources we needed in our schools and our communities. Most of us have done very well. Of course, there are others who have not, but I think that’s probably the case for most communities.

RS: And it’s often hard to tell — it’s not usually the homecoming king who becomes the great success in later life.

WH: Exactly. What I hope to have captured in the book is what a major difference it makes feeling loved and supported and getting the proper nurturing from the community and your extended family and your neighbors. Being in an environment where people are looking out for you as you’re growing up. Our parents and the people in our communities recognized that they had to do that. If they did not provide this kind of attention and love — sometimes love that’s sort of overbearing — many of their young folks would not make it. In fact, too many didn’t, even with all the love and support. But without that care, you really had no chance at all. In writing this memoir, it gave me a greater appreciation for those people I grew up under and with. I’d had a lot of questions about why people in my community were accepting of things such as not being able to vote or go where they wanted. Why accept that? In trying to find answers, it led me to become an activist. Trying to find answers, and then, with those answers, trying to do something about the situation of the world I inherited.

RS: It seems that even prior to becoming an activist you were a news junkie.

WH: Oh, yeah.

RS: You loved the paper.

WH: Yeah. I think that was the writer in me. I read everything I could get my hands on, and I started writing when I was very young, elementary school. I was looking for more knowledge, more information to help inform the world that I was living in. But I also wanted to know what it was like beyond Mansfield. What were kids my age doing in New York, in Hong Kong, in Berlin? What was their living style like? I was always curious. So I did a lot of reading. I followed the news. My grandfather and my father did as well. There’s a scene in the memoir when I’m about eleven years old, and I’m sitting with my grandfather, who was a news junkie too. He listened to the radio — that’s where he got his news. We used to sit on the porch, a little kid and an older man, just talking about world events. Some of the adults used to say I was older than my age.

RS: Well, it seemed for a while there you might have become a preacher.

WH: I think I was being groomed to be a preacher. It’s what the adults saw in me — my love and appreciation for people. I had — still have, I think — a big heart, and people recognized that. I was a giving person. Given the religious grounding that people in my community (and Black people in general) had, preaching was the profession they recognized was most needed in the community. Teaching was also valued, but many of the civil rights leaders and the freedom fighters of slavery were preachers. Frederick Douglass, Sojourner Truth. Richard Allen, who started the AME Episcopal Church, was a preacher in his twenties and became an ordained pastor before he was forty.

RS: Sometimes it seems to me like the psalms are all about justice.

WH: Yeah, achieving justice, but also about living a good life. The struggle was obviously about justice, freedom, equality, and all of that. But what was also put forth for us to look at and analyze was living a life of worth and value — even if that life was still hampered by Jim Crow and you really couldn’t achieve the freedom you knew you deserved. It’s a twin approach to living, fighting for freedom but also being a good person. There’s an old saying in the Black church: “May the work I’ve done speak for me.” That includes fighting for freedom, but also doing good deeds for those around you. Those were both major in our community.

RS: After Jackie Woodson published Brown Girl Dreaming, I asked her how much she had to check her memory. She basically said: "All the time."

WH: Same here. I remember incidents and people very well, but I have a problem with dates. I am blessed to have my brother, who’s a major character in my memoir — he’s a year and a month younger than me — so I could always call him up, and he could always provide that perspective. He was instrumental in helping me to write this memoir. What I also tried to do was give historical background, what was happening during the time that I was growing up and coming of age, and what impact those events and those tragedies had on me at the time. Those incidents — the four little girls being killed in that church bombing in Birmingham, Emmett Till, the Little Rock Nine integrating Central High School — I saw those stories on the news. I followed them in newspapers and magazines. They had an impact on me and how I saw myself, and also how I saw the people around me. Mansfield was so segregated and so much under the control of the white power structure, there really wasn’t any major movement for freedom there until after I went to college.

RS: I remember you saying in the book that the first time you saw a white child wasn’t until you were in junior high.

WH: Actually, my first time facing violence because of my color happened when I was on my way to town, going a route that I’d never gone before. I ran into these three white boys, who threatened to beat me up. They were looking for some other Black guy, and they thought I knew where he was. Again, our communities were pretty much self-contained. From time to time we’d think of going downtown where the stores were, to buy clothes and things like that, but other than that, all of our time was spent in our own community. We had our own corner stores, cleaners, churches. There were two worlds. There was a Black world, where I grew up, and there was a white world, that I knew very little about.

RS: How does that compare to your own children’s childhood?

WH: It’s very different. My son and daughter both went to predominantly Black schools, because East Orange, where we live, is eighty-five percent Black. We moved to this area in 1974 which, at the time, was maybe forty percent Black. Over the next ten years it quickly turned into a predominantly Black city. So our kids grew up in a mostly Black school system. But many of our friends, in publishing, and I was a playwright, too — the kids were exposed to people of different cultural backgrounds and different ethnicities. Their upbringing was very different from mine and my wife’s. Cheryl grew up in Portsmouth, Virginia, in a similar all-Black community, all-Black world, all-Black school system as well. Both my son and my daughter went to state colleges in New Jersey. My daughter went to Douglass at Rutgers, and my son went to Rowan University. Both of those schools were majority white, so they had interactions with people of different ethnicities and cultural backgrounds. But they also have benefitted from the close family ties that aided me, the extended family structure that’s there to support them through our community, and also through our church. Our church became, for us, more like the Black community in Mansfield was for me, and for my wife, where she grew up. Our kids still benefitted from a strong Black cultural support system.

RS: Even though theirs is a completely different era and a much more cosmopolitan setting.

WH: Exactly. It’s a much different world. The world that I grew up in — those experiences that helped mold me and pushed me to what I chose to do in my life — have become even more important as I sat down to write the memoir. All of it just came back as I was writing. I started to actually relive some of the experiences. And as I said earlier, I have gained greater appreciation for those people who I grew up under and who supported and loved me. I think I’d taken that for granted over the years, because I was more focused on finding my way and making my contributions without completely understanding how the contributions that they had given to me have enabled me to do what I do.

RS: But kids are naturally egocentric, right? You don’t think about the love surrounding you much, even while it’s supporting you and helping you along your way. You just expect it.

WH: That’s right. You assume that it should be there, so you take it for granted. But as you get older, and particularly as you have kids yourself, you start to understand how important it is to have a really solid foundation on which you can stand. And unfortunately, Roger, there are a lot of people who have not had that kind of support, that kind of grounding, that kind of foundation. Many of them struggle and are not able to achieve what they could if they’d had that support in place to undergird them. That’s one of the reasons my wife and I are focused on publishing books, because we want to reach those young people as well. It’s so important to value your past, the good and bad. Recognize the bad without duplicating it. Lift up the positive, because the positive helps point you to a better future. It’s important for young people to understand that they are connected to something of value, something important, as a foundation that even goes beyond their own personal families. It goes back to generations before their parents and siblings. It goes back to all those freedom fighters, Black folks who fought for freedom, who fought for a better life, who tried to open doors, and did in many ways. We owe a debt to them, as our parents pass on the baton to us coming forward. It’s a danger if you feel disconnected and like you’re just floundering out there. That’s a scary way to live one’s life.

RS: Certainly books are one way that you can give a kid an anchor. I see a direct line between Wade as an inquisitive child, Wade as a college activist, and Wade as a children’s book publisher. Do you see that line?

RS: Certainly books are one way that you can give a kid an anchor. I see a direct line between Wade as an inquisitive child, Wade as a college activist, and Wade as a children’s book publisher. Do you see that line?

WH: Yes. I think there’s a through line through most of my experiences and my endeavors in life. Writing this memoir helped me understand that connecting thread. It really does go back to Mansfield. Being inquisitive and wanting to know more about Black history, about the Black experience, and Black contributions to this country and to the world, helped me connect to an even larger family, in addition to my family and my people in Mansfield. That has given me an even greater motivation to move forward, because I recognize that I have ancestors who have a long history and a rich heritage, too, that’s passed onto me. The Black history, the Black culture — I’m obviously also benefitting from the history and culture of this country and the world, so being able to connect all of that is really crucial to feeling positive about oneself and having the aspiration and the spirit to believe you can do it. You can look back and see where others have done it too. It doesn’t mean that you’re going to be successful in everything, but having some success means that other successes are possible. If you believe that there has been no success, why would you think that success is possible?

RS: What do you think young Wade would have done, had there been the comparative wealth of Black history and Black literature for young people that you and Cheryl are helping to bring today? What if those books had been in your library?

WH: You know, I think about that a lot. It’s really a difficult question to answer, because I didn’t have them, so I had to find ways to find my humanity in the books that were available. It took work. But there are places where you can find yourself, even though you may be reading a book about a different life experience, a different culture. There are ways in books that humanity becomes common, but you have to work to find that. The culture or the setting of a particular story I sort of see as having clothes, and when you pull the clothes off — most of us have bodies and arms and legs. We may have different skin tones, or different language, but we all have basically the same body. We’re all human beings. Even those books that demeaned people who look like me, even watching movies growing up that portrayed Black people as buffoons, Stepin Fetchit and those characters that were recycled over and over again in the old movies that used to play on television late at night that I used to watch — Gone with the Wind, for example. I enjoyed that movie, but at the same time, I felt offended by it. There was a pleasure in seeing the story unfold — that’s the way I connected with it. I need to think more about your question. Would I have become the kind of activist that I became, if I’d had those books? If I’d had those books, I think it would’ve meant that my community would have been different.

RS: Everything would have been different.

WH: I certainly wish that I had, and I think I would really have embraced writing more fully when I was younger if I had known, for example, that Richard Wright had written Black Boy, that Langston Hughes and James Baldwin had written their wonderful bodies of work. None of those writers’ books were available to me when I was growing up. It wasn’t until I left home and went to college that I was introduced to all these great writers and these wonderful books.

RS: You made me think about a stereotype about boy readers. We say: “Boys don’t like to read.” But — it was reviewer Betty Carter from Texas who taught me this — boys don’t like to read what we want them to read. You were a huge reader, but you weren’t finding the stories you wanted in books. You were finding them in other places.

WH: That’s exactly right. I think that’s the case for most boys. My wife and I talk to young people a lot. I pay particular attention to boys, and particularly Black boys. What people tend to do is tell them what they should read without taking the time to figure out what they like to read. Oftentimes the books kids choose to read — we say these books are not literary. They’re not worthy. We kill their interest in reading. They just give up. We force a book on them that they don’t want to read, and they just sit there and look at the cover, and we wonder why they don’t read. When I was growing up, boys liked to read comic books. They read sports magazines. We’ve learned a whole lot more now than we knew then, those of us who teach and those of us who interact with young people — we should have encouraged them to continue to read those books, but to introduce other books along with them, rather than making it an either-or proposition. Superman and Batman and all those comics that were around when I was growing up — whether you were a Black or white boy, you identified with the characters. Sports biographies were really big back in the day. I read about Babe Ruth and Rogers Hornsby and those celebrated baseball players, and football players too. Very few were written about the Black players. I love baseball, so I connected to them through baseball, and I wanted to read those books about how they played the game, what they did when they were growing up, so I could maybe try to do what they did. Whether they were white or Black, it didn’t matter. It would have been more meaningful if I had a book about Hank Aaron, but they weren’t there when I was growing up. They are now. But again, the connection was I love baseball.

RS: “I love baseball; the guy in this book loves baseball — we have a connection.”

WH: That’s exactly right. Educators are starting to understand that you have to really connect with boys where they are, and then bring them along. The learning styles for boys are different than girls, particularly at a much younger age. Boys like to run and jump and throw, and they’re fidgety.

RS: Speak for yourself. I was a little bookworm, Wade.

WH: I was too. I was both. I was very engaged in playing and stuff, but I would always break away and find a book or watch some program on television that was of interest to me, while the other guys were out playing. I guess you would consider me a pseudo-bookworm, or a pseudo-nerd. At that time, no one really called you a nerd. A lot of the boys that I would call “incorrigible” — they honored guys who were smart. They would come to us when they needed information about something. When my son was growing up, it was different for him. The guys at school would put pressure on him if he made good grades, because it made them look bad. If he had a book in his hand, “Aw, man, put that book down.” But that wasn’t the way it was when I was growing up. I don’t know if you’re familiar with W. E. B. Du Bois’s Talented Tenth theory.

RS: Yup.

WH: Black people were looking for the smart guys — and girls, too, but mostly guys — to be among the Talented Tenth that would lift the race. They pushed us. They honored us. In high school, they honored all of us who made the honor roll. We had to stand up in assembly as they called our names. In the book, I share that there was a scholastic rally — if you won first or second place in the district competition, then you went to the state competition. Those of us who won first place or second place, we got standing ovations, and we were like kings and queens for a period of time because of our academic excellence. That started to change. I know for my son it wasn’t like that. For girls, now there are more Black girls who go to college, more Black women who now are professionals. The way Black boys were raised when I was growing up has changed to a large degree. I don’t think we have that same sense of community. There’s support, but it’s not as acute as it was.

With integration and having achieved some degree of success as Black people — many of us have become part of the middle class, and you see athletes and movie stars doing well, making a lot of money — that success, and having had success, tends to make you think that we’ve made it. When we were growing up, we knew we hadn’t made it, and we knew that there were few opportunities for us. If we were to survive, if we were to make it, if we were to have — as they would say back home — a halfway decent life, you needed to pull together to do that. You had to pull together. There was no other way. You couldn’t make it on your own, no matter how talented you thought you were — you needed other Black people to assist you and to be there for you. We knew that even if you achieved a small degree of success, chances are, at some point you’re going to fall back down. If you’re out there by yourself, then you’re alone. There’s nobody there to catch you. That’s the whole sense of community and banding together.

I finished a picture book manuscript that’s going to be published in 2023 by Calkins Creek. It’s called The Founding Mothers and Fathers of Black America. What I’m attempting to do in this book is to show how the Black community actually came about, and why it came about. During the beginning of slavery, as you know, Black people came from different ethnic groups in Africa, speaking different languages. But when they came here, it was their Blackness that was the common denominator. Those who were enslaved and those who were not enslaved did not have the same rights as white Americans in colonial America. They recognized that for them to make it, they had to establish their own. They had to support each other. They came from different cultures and spoke different languages and had different understandings about the world around them, but if they were to make it, they had to pull together. That’s why they had to form Black America, establishing their own churches and their own businesses, those who could.

RS: And their own publishing houses.

WH: Their own publishing houses, exactly. Recognizing the history. And it’s not just for Black people to know their history. It’s for all of us. One of the problems for most of us is that we know so little about folks whose life experiences are different from our own. The more that we learn about each other and our experiences, the histories of other people who make up this wonderful mosaic of America — if you don’t know what a person’s gone through, how can you really know them? Or if you don’t see them as fellow human beings, how do you have empathy for them when they’re going through some troubling times? You referenced books early on — I think that’s why books are so, so important. When I was participating in protests around the George Floyd shooting, I saw white kids from South Dakota and North Dakota and places where there are no Black people protesting. I started wondering how many of these young people have read books written by Jason Reynolds or Kwame Alexander or Jacqueline Woodson and others that have opened their eyes to those experiences that are different from their own. And because they did, they are now able to empathize with people who don’t look like them.

RS: I think you’re right.

WH: Those books are making a difference, particularly for young people. That’s where the hope for me really is. Most young people are more open and accepting and caring than the young people when I was growing up.

Sponsored by

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!