From Trend to Norm: How the Last Twenty Years of the Newbery Can Guide Us

Newbery Award titles are among the more visible of books for young readers. As such, they provide the opportunity to explore in microcosm a potential template that can be applied to the entire arena of books for children and teens.

Newbery Award titles are among the more visible of books for young readers. As such, they provide the opportunity to explore in microcosm a potential template that can be applied to the entire arena of books for children and teens.

Newbery Award titles are among the more visible of books for young readers. As such, they provide the opportunity to explore in microcosm a potential template that can be applied to the entire arena of books for children and teens.

My book A Single Shard won the Newbery Medal in 2002. Back then, it was only the second time in the entire history of the award that a creator of Asian heritage won the top prize. (The first Asian winner, also the first person of color to win, was Dhan Gopal Mukerji, for Gay-Neck: The Story of a Pigeon. In 1928!) Twenty years ago — that’s getting close to a full generation. A lot can happen in a generation.

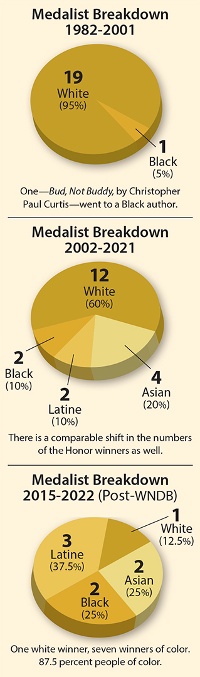

To put that particular time span into context, let’s go back a little further. From 1982 to 2001, twenty Newbery Medals were awarded. Nineteen went to white authors. That’s ninety-five percent. One — Bud, Not Buddy, by Christopher Paul Curtis — went to a Black author.

To put that particular time span into context, let’s go back a little further. From 1982 to 2001, twenty Newbery Medals were awarded. Nineteen went to white authors. That’s ninety-five percent. One — Bud, Not Buddy, by Christopher Paul Curtis — went to a Black author.

Now on to 2002–2021, the ensuing twenty years. Again, twenty Medalists. Twelve white, four Asian, two Black, and two of Latine heritage. Sixty percent white. There is a comparable shift in the numbers of the Honor winners as well.

The numbers clearly demonstrate that things are changing for the better, with Newbery books becoming more welcoming, more inclusive, more loving, of readers from all backgrounds. But wait, there’s more! Looking past the numbers, we can see how the Medal and Honor titles have expanded in scope and possibility. The awarded books by Black authors starring Black characters explore the vast territory beyond slavery and civil-rights narratives. A book about Black hair — boys’ Black hair. A story about a contemporary Black kid at a fancy private school, another about a girl who dreams of foreign travel.

Asian narratives, too, have pushed at the boundaries of what was previously considered their acceptable space. By scanning the list of winners and honor titles, we can trace the evolution from model-minority stories and historicals that were comfortable for white audiences (and I include my own A Single Shard in this group), to contemporary settings and characters for whom ethnicity is identity but not entirety, and a widening circle that goes beyond East Asian foundations to include Southeast Asian and South Asian stories.

Slowly but surely. Deaf representation. An Islamic main character. A contemporary Lipan Apache girl. As Newbery recognition has opened its doors to stories created by those from marginalized communities and centering kindred characters, something else has happened in tandem, to the further benefit of young readers.

A deaf character is the protagonist of Cece Bell’s 2015 Honor Book El Deafo. It was the first graphic novel to receive Newbery recognition. The next year, another graphic novel Honor followed — Roller Girl, by Victoria Jamieson. These two Honors paved the way for Jerry Craft’s New Kid, the first graphic novel to win the Medal, in 2020.

Latine books and authors have claimed a share of the spotlight in more ways than one. Last Stop on Market Street by Matt de la Peña, illustrated by Christian Robinson, was the first-ever narrative picture book to win the Medal (the only previous picture-book winner was the poetry collection A Visit to William Blake’s Inn in 1981). And this year’s Medal title, The Last Cuentista by Donna Barba Higuera, combines Mexican folklore with science fiction. Quick, what was the last science fiction book — not fantasy or speculative — to win the Newbery?! A Wrinkle in Time, in 1963! Almost sixty years ago!

It’s clear that form and genre possibilities have also expanded, to affirm more choices for readers. Not a coincidence! That’s how it works. When we focus on inclusion, equity, and justice, our minds and hearts are opened to further exciting opportunities. And historically, the evidence could not be clearer: whenever a society moves toward greater inclusion, all of its members benefit.

A final number set: Medal winners since 2015 (including the 2022 winner). Eight Medalists total. One white, two Black, two Asian, three Latine. One white winner, seven winners of color. 87.5 percent people of color.

A final number set: Medal winners since 2015 (including the 2022 winner). Eight Medalists total. One white, two Black, two Asian, three Latine. One white winner, seven winners of color. 87.5 percent people of color.

Why 2015? Because it was the first year of Newberys to be awarded after the formation of We Need Diverse Books, which itself came into being on the heels of the Black Lives Matter movement in 2013.

For me, the question now is, how do we sustain the change? What can we do to ensure that the trend becomes the norm — not only with award winners, but throughout publishing?

Hoping for the best is not enough. We have already seen evidence of backlash against this change and what it represents. Change often scares people, and that fear generates the fight reflex: all over the U.S., school districts are removing books in an attempt to keep justice and inclusion off the shelves and out of the curriculum.

I don’t know how it ends, but I know how it begins: by developing a habit I call Front of Mind (see sidebar below). Equity and justice need to be front of mind every day: every choice, decision, opportunity. Our personal and individual choices have the power to change institutions and systems — if enough of us make those choices.

Publishing employees and management. Agents. Teachers and librarians. Booksellers. Trade journals. The media. Bloggers, podcasters, influencers. Parents. Mentors. All of us, but most especially those from the dominant culture: imagine a world where everyone makes personal and professional choices informed by justice and equity.

Here I will use publishers as an example. The publishers that will thrive in the coming years are those eager to make the necessary changes to engage fully with marginalized communities. Publishers embracing this kind of change will produce books that will better serve both young readers and the bottom line. Among the Black, Asian, Latine, and Indigenous populations in the U.S., there was as of 2020 almost five trillion dollars of buying power. LGBTQ+, more than one trillion. Disabled, 490 billion. Not alternative income streams, but new ones.

It is not enough for dominant-culture folks to raise their own awareness. There is no substitute for lived experience. A plethora of data proves that work groups comprising people from different backgrounds outperform less-varied groups. The data bears out common sense: different lived experience = different perspective = different ideas = different solutions. When combined in group settings, the best of those solutions lead to greater innovation and productivity.

Front of mind: publishers need to upend their hiring practices so that the focus is to bring in not a handful of hires each year, but as many people from marginalized backgrounds as possible. Then they need to support those hires with both company policy and personal commitment. Listen. Make choices that diverge from the choices of the past.

The same emphasis on front of mind is needed for everyone who works to connect kids and books. Another example: when a reviewer doesn’t “get” a book, it might well be due to poor writing or an unconvincing story or flat characters. But what if the story is “unconvincing” because the reviewer has no lived experience in the world depicted in the book?

“Quality” in literature is a moving target, not an intrinsic trait. (If you disagree, have a look at the Newberys from the early twentieth century.) The canon of so-called classics has traditionally been determined almost exclusively by those from the dominant culture. When we make it a priority to widen the circle of those defining “quality,” we not only serve more readers, we serve all of them better.

The Newbery Award’s prominence means that, as the community of its caretakers, we bear a special responsibility to young readers. Over the past two decades, and especially since 2015, the award has been sending a message of greater inclusion, expanded possibilities, and more openhearted love. Starting this very moment, each one of us can begin or continue to make choices with inclusion, justice, and equity front of mind, whatever our role in the world of children’s books.

Front of Mind for Daily Life: How to Begin

From the May/June 2022 special issue of The Horn Book Magazine: The Newbery Centennial.

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!