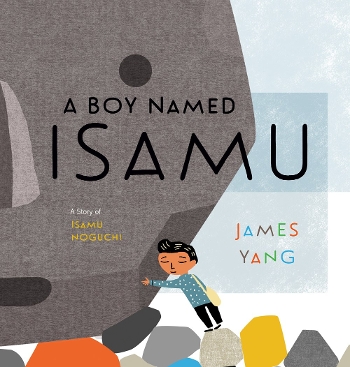

James Yang’s illustrations for A Boy Named Isamu see the world not just as a young Isamu Noguchi might have, but as any young child might. Textiles must be felt, leaves must be collected, sticks must be dragged through the sand, and bamboo must be played like a flute.

One of my earliest memories is of a preschool lesson in which my teacher had a large, clear tub of water and several small, everyday objects. She asked us to guess whether each object would sink or float, and we would watch her place the objects in the water to see if our predictions would be correct. I don’t remember what the specific objects were or even how she explained the science behind what we were seeing, but I remember the sense of wide-eyed wonder, the feeling that some mystery of the universe was being unlocked before my eyes — or rather opening them to an awareness of the wonder to be found in even the most ordinary things. That’s the sense James Yang conveys in A Boy Named Isamu, his picture-book not-quite-biography of the mid-century Japanese American sculpture and landscape artist Isamu Noguchi.

One of my earliest memories is of a preschool lesson in which my teacher had a large, clear tub of water and several small, everyday objects. She asked us to guess whether each object would sink or float, and we would watch her place the objects in the water to see if our predictions would be correct. I don’t remember what the specific objects were or even how she explained the science behind what we were seeing, but I remember the sense of wide-eyed wonder, the feeling that some mystery of the universe was being unlocked before my eyes — or rather opening them to an awareness of the wonder to be found in even the most ordinary things. That’s the sense James Yang conveys in A Boy Named Isamu, his picture-book not-quite-biography of the mid-century Japanese American sculpture and landscape artist Isamu Noguchi.

A Boy Named Isamu is unique in the world of picture-book biographies in that it doesn’t summarize Noguchi’s life or detail one of his greatest accomplishments. Instead, it imagines one possible day in Noguchi’s childhood and how it might have served as later inspiration for the ideas, materials, and shapes that made up his later work. It is also unique in that, though Noguchi is the protagonist here and his design aesthetics undoubtedly inform the illustrations, this is as much a book about young children and how they experience the natural world as it is about Noguchi himself. “If you are a boy named Isamu…” the text begins, “at the market with your mother, it can be a crowded and noisy place.” The text continues in second-person throughout, as young Isamu Noguchi — or you, imagining you were young Isamu Noguchi — wanders from the market to explore and contemplate the textures and shapes to be found in many quiet places.

Though this aspect of the book may not seem particularly relevant to a discussion of Caldecott-worthy illustrations, the choice to write in second-person for a child audience affects the way the reader perceives the illustrations. Reading, for example, the sentence “You toss the grass in the air and watch as the blades scatter in different directions” invites the reader to imagine the texture of the grass in hand and feel the breeze that scatters the blades in a way that observing the story from an outside lens would not. Ultimately, such text propels the audience deeper into the vibrant colors and textures of Yang’s illustrations. The gray stones in particular, of many sizes, shapes, and hues, come to life on the page and beg to be touched. This is especially true in one spread where a large boulder comes alive with facial features under young Isamu’s touch. The organic nature of Yang’s illustrations is even more remarkable when considering that they have been composed entirely digitally and retain many of the crisp lines and high-contrast colors common in Yang’s work, but without sacrificing the complete immersion in the natural world the book gives its readers.

Yang’s illustrations see the world not just as a young Isamu Noguchi might have, but as any young child might. Textiles must be felt, leaves must be collected, sticks must be dragged through the sand, and bamboo must be played like a flute. Though Isamu’s facial features are simple, in Yang’s signature style, small changes in mouth, eyes, and head position convey the full range of emotions Isamu experiences as he engages with his senses. We see wonder, curiosity, pleasure, and serenity play across his face, and, because we are Isamu here in this imaginative world, we feel those things, too. For adults, this experience takes us back to a time when the natural world was brimming with mysteries, but for children, it mirrors their current questions, imaginations, and sensory experiences.

It is this centering of children’s perspectives and their unique ways of engaging with the natural world that feels most relevant in the discussion of whether A Boy Named Isamu is Caldecott-worthy. When considering the Caldecott criteria of “excellence of presentation in recognition of a child audience,” A Boy Named Isamu more than fills the brief.

[Read the Horn Book Magazine review of A Boy Named Isamu.]

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!