So far, neither of us has successfully championed a graphic novel that has earned so much as an honor. But, this time, we submit two titles that we not only love but think have the potential to earn that coveted Caldecott gold or silver.

Two voices are always better than one, so we’re excited to co-author this year’s CaldeComics post (à la Elisa Gall and Jonathan Hunt).

We first became CaldeBuddies while we were at Simmons University together, each of us maxing out our library cards at the Boston Public Library’s Faneuil Branch in order to run our own modest Calling Caldecott bracket. After we both graduated, we nurtured a Google doc in which we would write our thoughts about each year’s slate of picture books. All to say, having both of our names on this byline feels both inevitable and also wonderfully surreal. We can’t wait to dig in this year, together.

So far, neither of us has successfully championed a graphic novel that has earned so much as an honor. But, this time, we submit two titles that we not only love but think have the potential to earn that coveted Caldecott gold or silver. This year, more than any other, we also want to acknowledge the number of top-notch graphic novels published outside the United States that are, unfortunately, ineligible.

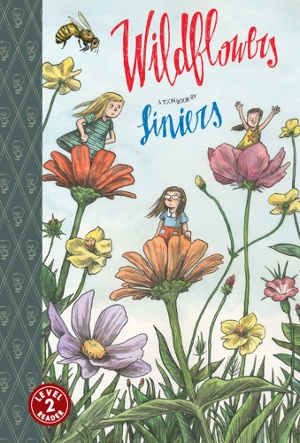

Wildflowers b y Liniers

y Liniers

NIKI MARION: I love a story ending that makes me want to reread it immediately to catch all of the details hiding in plain sight, and Liniers’ Wildflowers absolutely has this effect. The final two spreads of this early graphic reader completely retexturize this story’s setting and scope, and what readers believe is an elaborate, fantastical island is perhaps much closer to home. The book’s penultimate spread features a montage with alternating bordered and borderless panels. The bordered panels contain key items from earlier illustrations: a toy plane in the exact position of the crashed jet, a bag of popcorn, a stuffed gorilla. The borderless panels are portraits of lush, exuberant wildflowers—dwarf red cosmos, zinnia, rose of sharon*—three flowers, three girls, three imaginations. The final bordered panel shows these flowers in the background, just across the grass from other discarded toys. The fantastical island is ... made-up?

As readers complete the page-turn, they then see the girls running across a field of negative space, fully transitioning readers into the true(?) setting of this story: the sisters’ very own backyard. But in the bottom right-hand corner of the final image, a wildflower with a smiley center at once calls back to the smiling flowers that appear at the book’s onset and hints at the unlimited magical potential of playing in the great outdoors. That Liniers gracefully accomplishes this reveal in just two spreads with very little text at all is truly marvelous.

*[My best friend, Hannah, is a botanical hero and helped me to guesstimate what wildflowers Liniers included. She also informed me that butterflies love all three of the featured blooms, so it’s no wonder our friend Bill the butterfly shows up right at the end!]

ALEC CHUNN: I’ve heard a few different people draw comparisons between Wildflowers and Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are — and for good reason. Both books utilize similar framing techniques to blur the lines between reality and make-believe. Most often the illustrations completely break out of the panels when the sisters imagine something for the first time. The boldest example of this is the double-page spread depicting the dragon crawling through the trees, one claw just barely crossing the gutter, toward the girls. The layout brilliantly creates tension. But without the book’s expert pacing it wouldn’t have nearly the impact that it does. The small panels on the previous page home in on the sisters’ snippets of conversation, making the page-turn feel loud and explosive even though the dragon doesn’t utter a single sound.

Pacing also contributes to the book’s “and it was still hot” moment — the moment that makes readers rethink the narrative and question what’s real and what’s not. That moment, which Niki homes in on above: the single smiling flower outside the house. If the Real Committee could consider text, too, the realization that Bill the butterfly really exists is another contender. Either way, these delightful surprises offer a double-take on the previous spread’s reveal. Careful readers may notice clues all along — such as the two striped red lines on the fantasy sign that call to mind notepaper — and these details encapsulate the criteria of “excellence of pictorial interpretation of story, theme, or concept.”

ALEC & NIKI: One of these small details the Real Committee is going to need to look especially closely at, however, is the representation of the gorilla. Thanks to Edith Campbell’s research, “Why a gorilla?” or “Why a monkey?” is a question we now ask every time we encounter an anthropomorphic simian in books for young readers. Is the gorilla merely a toy? Or, intentional or not, is it a racist stand-in for a Black character? It's an important point to consider when awarding one of the highest honors in children’s illustration.

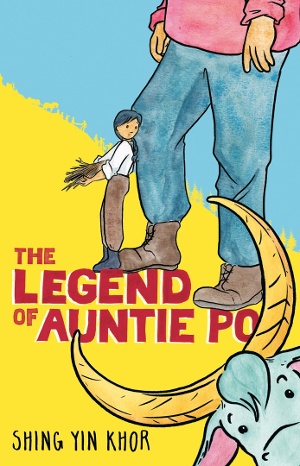

The Legend of Auntie Po by Shing Yin Khor

The Legend of Auntie Po by Shing Yin Khor

NIKI: There are so many striking elements to marvel over in Shing Yin Khor’s breakthrough graphic novel. For one, Khor works in digital pencils with hand-painted watercolors — yes, hand-painted — which they often use to tint the gutter. This inspired choice can make the sequential art feel warm and cozy or extremely tense, depending on how it impacts the negative space within the panels. One wordless double-page spread illustrates both extremes. In the spread’s top third, Bee stands in profile facing a seated Mei, who holds her knees and avoids Bee’s eyes. They each perch on top of a column of three panels, separated by the gutter; visible brushstrokes of pigmented black ink bridge (yet confirm) the gap between them. Khor, however, colors the rest of the space in between the panels, which show Bee only on the left page and Mei only on the right, in a golden hue, signaling the friends’ nascent reconciliation in the final panel before the page-turn. This is just one of many sequences made spectacular by Khor’s use of the entire page.

Khor also hand-letters the fonts used throughout the book. Even the Cantonese characters were handwritten by Khor’s mother! Now, Alec and I count hand-lettering as art to be considered by the Caldecott committee. Whether the Real Committee does or not is up to them. But the mastery is in the details, especially in this book.

Additional ingenious feats of small design, such as repurposing panel edges in adjacent illustrations (Khor reimagines a panel bottom as a kitchen rack from which to hang pots and pans), work overtime to elevate the visual narrative.

ALEC: The fact that Khor’s mother hand-lettered the Cantonese characters still gives me goosebumps. Connection to family is clearly evident in this book, as the dedication goes out to Khor’s father. I absolutely love the spread Niki describes, because it also exemplifies Khor’s brilliant use of silence in this book. While readers would miss a lot of context without all the dialogue (a potential ding depending on how the Real Committee interprets the criteria), Khor’s visual storytelling chops make for plenty of wordless moments that get readers to slow down and sit with key moments. There are giggles, there are tears, and there is wonder. No words needed.

I was also transfixed by all the campfires in this book. It could be the way the warm colors stand in stark (and beautiful) contrast to the cool of the night. But the campfire is also a gathering place, a storyteller’s pulpit. Mei first introduces Auntie Po at a campfire, her likeness appearing in a speech bubble before words explain her story. This technique of using an image in a speech bubble is later repeated in one of my favorite moments. After tragedy strikes, young Henry tells Mei he sees Auntie Po saving his dad. After hearing all of Mei’s stories, he finally believes Auntie Po to be real. The panels show Henry with the version of Auntie Po depicted throughout the book. But when Henry retells the story a few pages later — alas, not at a campfire — the Auntie Po image that appears in the speech bubble is brown-skinned like him. A closer reading — notice the familiar pink bonnet and orange outfit — cues that Henry’s Auntie Po bears some resemblance to his own mother (if it isn’t her altogether). This pivotal sequence is not just about believing or seeing yourself reflected in legend but perfectly encapsulates the book’s theme of the power and legacy of stories as they change “when we share them with new people.”

NIKI & ALEC: Though there’s never a shortage of amazing picture books to consider, we hope that the Real Committee will discuss one or both of these graphic novels. Are there any graphic novels you’re cheering for?

[Read the Horn Book Magazine reviews of Wildflowers and The Legend of Auntie Po.]

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!

Tenisha McCloud

Sometimes a gorilla is just a gorilla. Just because Edi says something is true doesn't make it so.Posted : Nov 24, 2021 04:42