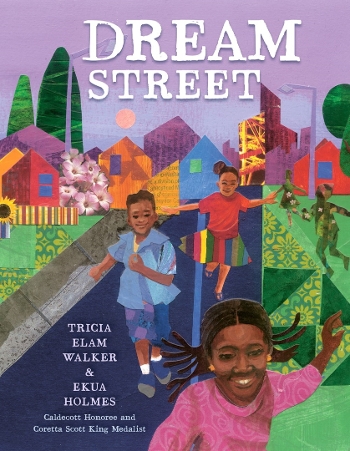

Dream Street, the locale for this breathtaking book of the same name, serves as a garden for growing a thriving community, rich relationships, and strong children who know who they are and what kind of difference they want to make in the world. “Welcome to Dream Street—the best street in the world! Just ask people who live here.”

Dream Street, the locale for this breathtaking book of the same name, serves as a garden for growing a thriving community, rich relationships, and strong children who know who they are and what kind of difference they want to make in the world. The picture book opens with a warm welcome to readers and a second-person address: “Welcome to Dream Street—the best street in the world! Just ask people who live here.” By directing readers to “ask people who live here,” not "there," the speaker invites readers not to observe from a distance but to get an intimate experience of this tight-knit, urban Black community.

Dream Street, the locale for this breathtaking book of the same name, serves as a garden for growing a thriving community, rich relationships, and strong children who know who they are and what kind of difference they want to make in the world. The picture book opens with a warm welcome to readers and a second-person address: “Welcome to Dream Street—the best street in the world! Just ask people who live here.” By directing readers to “ask people who live here,” not "there," the speaker invites readers not to observe from a distance but to get an intimate experience of this tight-knit, urban Black community.

Each double-page spread features a snapshot of individuals both young and older whose names—Biko, Yusef, Azaria, Zion—suggest that Dream Street is a microcosm of the African Diaspora. For some characters, Ekua Holmes creates detailed facial features; for others, none at all. But regardless, the beauty of their blackness shines through. For instance, we meet the five Phillips brothers, each of whom was named for a different jazz musician whose name starts with D. They pose together for their dad’s inspection, “from hats down to shined shoes,” before they go to church. Each one a dapper dresser, the Phillips brothers wear bow ties, striped or plaid summer jackets, and a hat worthy of a jazz musician. These light-colored jackets stand out against the vibrant and variegated patchwork quilt background that features one square with the bell of a silver horn and another with sheet music.

While most of the book concentrates on the children of Dream Street, the adults who appear nurture and focus on young people, whether they are related to those children or not. Mr. Sidney sits on his stoop and reads the newspaper, always modeling the importance of literacy, reading, and staying informed. Dressed “to the nines,” Mr. Sidney wears black slacks, a jacket, fedora, and dress shoes and carries a cane, be it for fashion or necessity, and his dark clothes contrast with the bright yellow steps on which he sits. Dressing this way just to greet and encourage his neighbors shows the respect he has for them and how much he loves living on Dream Street.

Conveying the importance of a different form of literacy, Ms. Sarah, also known as The Hat Lady, whispers stories in her quiet voice to those who come close. And readers who look closely at Ms. Sarah’s image will see that she is literally made of words: collaged painted pieces of newspaper in many shades of brown comprise her neck, her red and orange scarf, and her face, shown in profile. Dessa Rose also wears green clothing made of words. She grows colorful flowering plants and fragrant trees under which she rests with her grandbaby, Little Song, who naps on her chest. Wearing long locks that, like the plants framing the image, took years to grow, Dessa Rose is an Earth Mother figure who, like Mr. Sidney and Ms. Sarah, helps children grow their dreams.

When the children dream of bright futures, those around them help to light the spark and fan the flame of their hopes. For instance, Belle, who wants to be a butterfly scientist (a lepidopterist) when she grows up, catches and releases butterflies near the birdbath in the yard of her great-auntie, Ms. Sarah, The Hat Lady. Belle has learned to study the insects up close without harming them and has also learned a lot about them, such as that each is unique, like snowflakes. Belle’s profile, primarily in warm yellows, has the image of 25 different butterflies on it, with tic tac toe lines imposed on top of the whole illustration. Several of the butterflies as well as a piece of Belle’s shirt are made from newsprint on which the painted-over letters can still be seen. Belle says, “Everything has a right to be free,” an important idea that underlies most of the vignettes: education leads to freedom. This certainly rings true for Zion, a brown-skinned boy who visits the library “to read skyscraper-tall piles of books that take him on adventures around the world.” Literally surrounded by words and graphics that foster dreaming, Zion sits between shelved library books and a big stack of books with beautiful covers that he has chosen and reads an open book on his lap as he sits on a bench made from a world map. Surely, Zion will go far.

The centerpiece of the children’s vignettes, though, is the one about Ede and Tari, two Black girls who create together. Ede makes art while Tari writes, as they sit and lie on the floor, surrounded by their creations, and plan to make a book together some day. Ede prefers found art; she “collects smooth rocks, broken jewelry, leaves and feathers,” which she integrates into her artwork. And Tari “pays attention when new folks come around so she can make up stories about them.” Two pieces of art hang side-by-side on the blue wall behind the girls, and the greens, blues, oranges, reds, pinks, and purples in the art echo the colorful outfits the girls wear. Ede, who sports high-top sneakers, leggings and a short, pleated, tutu-like skirt, draws with what looks like a small twig, green leaves still attached, and Tari wears multi-colored polka-dotted pants, brown and tan saddle Oxfords, and a big pink hair bow — details that point to their artistic personalities. Best of all, the afterword identifies these girls as the creators of this book: Ekua is Ede, and Tricia is Tari. They conclude the note with these words: “As children, we loved what we loved (drawing and writing) and were always encouraged by friends and family. Now we know, and want you to know, that dreams do come true (with lots of hard work along the way)!” The dedications, which come at the end of the book, further affirm the book’s theme: each creator dedicates the book both to her mother and to her aunt, the other’s mother. Walker says her aunt was “small in stature” but was a “strong, forthright mountain of a woman,” who “steadfastly displayed your love and your pride,” while she credits her own mother with teaching her to love and respect words. Holmes labels her aunt “our very own librarian, storyteller, aunt, mother, counselor, encourager, and friend” and thanks her mother who, “against advice,” allowed her to dream of becoming an artist.

Anyone who reads Dream Street will also be glad that these women and this place nurtured the book’s creators. Dream Street is an exquisite work of art that offers tangible evidence of what happens when a village accepts the challenge of raising its children.

[Read the Horn Book Magazine review of Dream Street.]

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!