Happy Anniversary: All-of-a-Kind Family

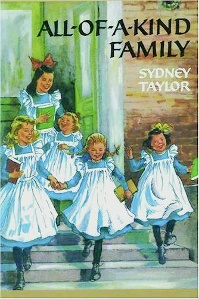

All-of-a-Kind Family by Sydney Taylor, illustrated by Helen John, was published by Follett in 1951, the first in a series of five novels. Taylor became the namesake for an award administered by the Association of Jewish Libraries for books for young people that “authentically portray the Jewish experience.” Here, Schneider reflects on All-of-a-Kind Family’s significance on its seventieth anniversary.

For women of my generation, specifically Jewish women, it’s difficult to convey the impact of Sydney Taylor’s book series about five Jewish sisters living on the Lower East Side of Manhattan in the early twentieth century. The five episodic illustrated novels about Ella, Henny, Sarah, Charlotte, Gertie, and their family were in a unique category of my childhood reading because the characters were Jewish like myself, but that was far from their only value. If it were, the books would be merely an artifact of Jewish American culture; in fact, children who are not Jewish have also been enthusiastic readers of the All-of-a-Kind Family series. The stories were a vividly imagined world into which I, and many others, entered again and again.

The first book in the series, All-of-a-Kind Family, was published in 1951, a few years after the Holocaust. The close-knit immigrant communities described by Taylor in homage to her own childhood, well before that tragedy (she was born in 1904), were also rapidly changing. There were unmistakable points of contact between my experiences growing up in 1960s Long Island as a grandchild of Jewish immigrants from Poland and those of Taylor’s characters. Her rich descriptions of Jewish religious practices and community life were striking additions to the range of experiences I encountered in my reading.

The first book in the series, All-of-a-Kind Family, was published in 1951, a few years after the Holocaust. The close-knit immigrant communities described by Taylor in homage to her own childhood, well before that tragedy (she was born in 1904), were also rapidly changing. There were unmistakable points of contact between my experiences growing up in 1960s Long Island as a grandchild of Jewish immigrants from Poland and those of Taylor’s characters. Her rich descriptions of Jewish religious practices and community life were striking additions to the range of experiences I encountered in my reading.

Jewish holidays play a large role in All-of-a-Kind Family — much as Christian holidays featured prominently in many other favorite books of my childhood, such as Little Women, which memorably begins with “Christmas won’t be Christmas without any presents.” The All-of-a-Kind Family series was based on the calendar of the Jewish year, featuring not only Chanukah and Passover but also the important festivals of Sukkot, Simchat Torah, and Purim. By describing holidays that were not just treated as compensation for the absence of Christmas, Taylor proudly acknowledged that being Jewish was different. Her vivid scenes featuring customs that would have seemed exotic to most Americans, such as dancing joyously through the synagogue with Torah scrolls or the raucous excitement of Purim, were true innovations in mainstream American publishing. For the first time, they were there, and positively portrayed, for everyone to see.

However, children do not enter into the lives of literary characters only when these are embodiments of their own ethnic, religious, class, or immigrant identities. Just as non-Jewish children might enjoy reading about Jewish holidays, Taylor’s books were valuable to me because that world complemented, but did not replace, the other classics, which I also embraced.

Even chapters less driven by explicitly Jewish content alluded to cultural realities common among immigrants and children of immigrants. The chapter “Sarah in Trouble” is specific to the All-of-a-Kind sisters’ experience in an immigrant family, with its focusing on rigid codes about food, which were common in first-generation homes. The sequence of dishes was so important that the girls had memorized it as a chant, beginning with “No soup / No meat…” and culminating in “No penny.” Conflicts between children and adults in other classics, such as Anne’s stubborn denial of an apology to Marilla’s insensitive friend in Anne of Green Gables, might be just as enthralling to readers from any number of cultural or socioeconomic backgrounds, but Sarah’s insistence that she would “choke” if forced to consume her mother’s delicious soup held particular resonance for children and grandchildren of immigrants.

Some differences between the more mainstream classics and Taylor’s books were more subtle but were still evident to me as a child. In Little Women’s “Castles in the Air” chapter, the four sisters discuss visions of their respective futures. Although these dreams may not be entirely realistic, they are a clue to the breadth of possibilities in their imaginations. Meg, for instance, hopes for a life of luxury with “plenty of servants.” Amy longs to create art in Europe; her ambition is fulfilled later in the novel. In contrast, the tenement-dwelling girls of All-of-a-Kind Family, in the privacy of the room that all five share, anticipate more modest prospects. In the chapter “Who Cares If It’s Bedtime?” Ella and Sarah “built their imaginary house,” choosing colors and detailed furniture arrangements. The theme of this conversation might seem sadly narrow, compared to studying in Europe or achieving great wealth, but in the context of the time it is both realistic and moving. The limitations of their living space, as well as the role of their mother as a skillful homemaker, influenced the girls’ ambitions. Acquiring and decorating a nicer home reflected women’s hope of upward mobility in many Jewish immigrant families. I identified with all these quirky and determined girls’ emotional conflicts and wishes, and the social challenges they faced, regardless of the similarities or differences in our backgrounds and circumstances.

In fact, the abundance of interaction between the Jewish characters and their non-Jewish neighbors in the All-of-a-Kind Family books furthered this sense of connection. Few children’s books before Taylor’s included Jewish characters at all, while some of the classics revealed unthinking moments of antisemitism. (In Anne of Green Gables, it is a manipulative Jewish peddler who sells Anne the dye that turns her hair green.) All-of-a-Kind Family and its sequels sent a hopeful signal about coexistence in America, presenting non-Jewish characters who became as close as family members to their Jewish friends. Characters such as Miss Allen, the “library lady” who goes out of her way to encourage the children of Jewish immigrants, and Charlie, the “handsome, blond, and blue-eyed” young man with a secret past who shows up in Papa’s junk shop, represent a change (albeit in a somewhat idealized way) from life in Europe, where Jewish-Christian interactions were often marked by hostility and violence. Shared celebrations of the Fourth of July and mutual interest in one another’s holidays emphasize the commonalities of life on the Lower East Side. This vision also allowed non-Jewish readers to comfortably identify with Jewish characters whose Christian neighbors were allies, not threatening adversaries.

This contrast between past and present (i.e., when the books first appeared) was part of the key to their success. Rather than emphasizing the singularity of Jewish life, the All-of-a-Kind Family books assured Jewish readers that, in fact, they did not have to choose between identifying as American or as Jewish, in an era when Jews still occupied an ambiguous and sometimes fragile place in American life. After World War II, Jewish Americans increasingly became more educated and financially secure, and many moved to suburban areas. At the same time, the trauma of the Holocaust had sent to America survivors whose recent experiences would seem to negate the optimism of Taylor’s books. I remember having a dual sense of the books’ relevance and the ways things had changed, even if I would not have used those words to describe my feelings. Today’s Jewish readers may feel distant from that era of significant progress toward acceptance in America, yet also feel continuing vulnerability. Rising antisemitism reminds us of its relevance.

Taylor’s introduction to the original edition of her first book contains this hopeful statement: “Here is a happy, human, satisfying story that girls and boys — and grown-ups, too — will love to read again and again.” (Sadly, I remember the books as almost exclusively read by girls.) Ella, Henny, Sarah, Charlotte, and Gertie were not merely nostalgic constructions meant to fill a void in children’s literature for Jewish readers. They took their place alongside all the other memorable characters who sought to find a distinctive place for themselves within their family, community, and the larger world.

Today’s readers may appreciate the books less as a reflection of their own experience, but with a new sense of curiosity. For those of us who read All-of-a-Kind Family close to its original publication, it confirmed our connection to a receding past and validated a Jewish present and future in America. Now that future has arrived, and All-of-a-Kind Family still resonates, thanks to Sydney Taylor’s compassionate and detailed picture of Jewish American life.

From the November/December 2021 issue of The Horn Book Magazine.

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!