Julian Randall Talks with Roger

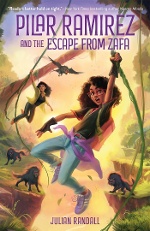

I’m always happy to meet a fellow fan of D’Aulaires’ Book of Greek Myths, and first-novelist Julian Randall, author of Pilar Ramirez and the Escape from Zafa, and I talk below about how he married his childhood passion for mythology and fantasy with a modern tragedy — the murderous Trujillo regime in the Dominican Republic — that brought his family to the United States two generations before him. And he’s a Chicagoan!

Talks with Roger is a sponsored supplement to our free monthly e-newsletter, Notes from the Horn Book. To receive Notes, sign up here.

Sponsored by

I’m always happy to meet a fellow fan of D’Aulaires’ Book of Greek Myths, and first-novelist Julian Randall, author of Pilar Ramirez and the Escape from Zafa, and I talk below about how he married his childhood passion for mythology and fantasy with a modern tragedy — the murderous Trujillo regime in the Dominican Republic — that brought his family to the United States two generations before him. And he’s a Chicagoan!

Roger Sutton: Did you grow up in Chicago?

Julian Randall: I’m from Logan Square, just off Western. I’m originally from there, was out of the city for a year and a half in middle school, came back, did eighth and ninth grade at Parker, Dad lost his job again, had to dip, and finished high school in Minnesota.

Julian Randall: I’m from Logan Square, just off Western. I’m originally from there, was out of the city for a year and a half in middle school, came back, did eighth and ninth grade at Parker, Dad lost his job again, had to dip, and finished high school in Minnesota.

RS: And you came back home.

JR: Yeah, now I’m back — I’m in Garfield Park these days, working on books. This is home like nowhere else is. You must understand that.

RS: I know. I grew up here in Boston, but I went to Chicago for graduate school and then stayed for twenty years. It still feels like home.

JR: Exactly.

RS: So, tell me what it was like to move from poetry to fiction.

JR: It was a fascinating process because everything is both very similar and very different. Learning how to listen to what a poem needed was my first real practice with knowing how to listen to a character, to figure out what a book project may be missing. I don’t necessarily want to call it a growing pain, but that was the first big transition — understanding that for these characters I am the driver of the story, whereas with a poem it’s more about receiving. It’s like the distinction between documentary filmmaking, a nature documentary, say, and stop-motion filmmaking. A poem is about finding the most intriguing angle, waiting for something surprising to happen, and following that surprise, whereas with my story characters, it was more a stop-motion approach. I have to get in there, to be in conversation with them. I have to be moving things around, to nudge them and push them in a way that poetry often doesn’t respond well to. Just finding that medium was definitely fun and a challenge. Poetry-wise, I come from a slam background, so a lot of my early work was done in persona, in this distance between the personal, factual, and performance. The training from that kind of characterization work also helped make the transition less bumpy.

RS: If I’m understanding you correctly, you’re saying that poetry really begins in observation, and with a novel, that’s never going to be enough.

JR: Absolutely, and definitely not. The first couple of novels that I tried to trot myself out on taught me that. You can’t just hope to get it all done in one shot — that was also a big transition point. With a poem, for me, the first draft has to all happen at once, or I can rarely find my way back into it. But you can’t do a novel all in one shot. That would be absurd — it’s a silly thing to try and take on.

RS: I think that’s why I was drawn to book reviewing — my need for instant gratification. I sit down, I write the book review, and I’m done.

JR: I love that.

RS: But you can’t really do that with a novel.

JR: You really can’t. It’s so much about day to day, showing up, creating ritual. I can’t do a poem every day. I’ve tried so many 30/30s, and ultimately end up with, like, three poems I’m really proud of and six haikus I did out of obligation. But writ large, working on this book was a joy. Pilar was like a younger sister who I visited every day to help direct her story.

RS: What did you have at the start of the project? Did you have Pilar? Did you say, “I want to write a fantasy novel”?

JR: That’s a great question. Pilar came about almost as a prompt. My agent, Patrice [Caldwell], had asked me, over the general course of one of our calls, if I had any interest in pitching a middle-grade Dominican-centric fantasy. It had already been on my mind for a while — I had a vague idea about one day wanting to address the questions I’ve had from third grade until basically college, about why there weren’t those types of books for my reading level (or teachers who had read the books that were at my reading level). I had always wanted to do something to that effect, and when Patrice called and asked — I hit her with a pitch in a couple of hours. Pilar, as a general concept, just strolled into my head fully formed. In the weeks that followed, it was a lot of referencing back to what I knew about Dominican mythology and what my mom knew about it. Carmen came next, and then the Galipote Sisters. The concept of El Cuco being in league with Trujillo was there from the onset — I always had my main antagonist and protagonist. Everything else filled in as I was doing more reading, researching, and conceptualizing of this world.

RS: When I went to read up a little bit about Dominican mythology, it was difficult to find English-language sources. I knew about the backward feet, but that was all I came in with.

JR: For sure. It’s definitely one of those things where a lot ends up getting lost if you don’t have an English-language source. I have enough Spanish that I can tell generally what people are saying to me, but I am not a fluent speaker. It meant that a lot of my research had to be counterbalanced by checking with Mom. That was one of the greatest permissions that Patrice and Brian [Geffen], my editor, both gave me. To be accurate to the story I wanted to tell and the traditions I wanted to tell it with, but also to understand that everybody has different understandings of those myths. So I was free to reinterpret the idea of there being multiple ciguapas, for instance. How could a Dominican brujería-influenced and -sourced magic system interact with Zafa, which was more a space of my own creation; and what does that look like in the format of a Dominican middle-grade contemporary fantasy?

RS: You mentioned that you were a big fantasy nerd when you were a kid. What books would you point to as great?

JR: I was a tremendous Artemis Fowl stan as a kid. You can definitely see some corollaries with my work and Eoin Colfer’s reimagining of those creatures — what does a goblin look like? What does a fairy mean? The idea of LEPrecon actually being leprechaun was so huge for me.

RS: Also the snarky humor.

JR: Absolutely. He was the first person I ever read who sounded as snarky as I imagined myself to be in my head. To this day I own all but one of the audiobooks on CD. My parents also had to listen to Artemis Fowl nonstop on a loop, and they liked the books, but they were not as enamored of them as I was. They ended up getting me the His Dark Materials trilogy by Philip Pullman, also on audiobook. That was mind-blowing, and foundational to who I am as a writer. The epigraph he uses from John Milton is one of the first poems I ever read and memorized. I owned the D’Aulaires’ Book of Greek Myths and read that thing cover to cover. My poor mother had to sit next to me while I watched Hercules the animated series and pointed out all the inaccuracies.

RS: We have the paperback in the office, and I stole it. I was like you — I would just read that book over and over.

JR: It is the one.

RS: I still see those gods and goddesses from those pictures.

JR: Absolutely. It changed my life in a huge way. I also want to give a shout-out to the Deltora Quest series by Emily Rodda, which was popular in the early to mid-2000s.

RS: Post–Harry Potter.

JR: Yeah, it was in that time period.

RS: One thing I’m finding so interesting in the most recent diverse books movement is the number of great fantasies. I thought we would see a lot of realism: “Julian writes a coming-of-age story set in Logan Square about real people.” And of course we’re getting those. But we’re also getting these amazing fantasy books. Rick Riordan has devoted a whole imprint to books from underrepresented cultures. What did having a fantasy element in your book, which has some very serious themes — particularly about what happened in the Dominican Republic under Trujillo — give you? What can you do in a fantasy that you can’t do in straightforward realism?

RS: One thing I’m finding so interesting in the most recent diverse books movement is the number of great fantasies. I thought we would see a lot of realism: “Julian writes a coming-of-age story set in Logan Square about real people.” And of course we’re getting those. But we’re also getting these amazing fantasy books. Rick Riordan has devoted a whole imprint to books from underrepresented cultures. What did having a fantasy element in your book, which has some very serious themes — particularly about what happened in the Dominican Republic under Trujillo — give you? What can you do in a fantasy that you can’t do in straightforward realism?

JR: I think my grand attraction to fantasy — and to a certain degree we can say this about all people — comes from being cognizant of and deeply curious about power and its manifestation. From a very young age I wondered: Did I have any power? If so, where does it come from? Can I get more of it? Do I need more of it? What happens if I get more of it? Where do kids get agency and get power from? I also love the idea that in fantasy, power and imagination don’t necessarily have to be opposites. The way power often showed up in my life was very anti-imagination. And because my relationship with the Dominican Republic as a space — I didn’t live particularly close to my tías or my cousins. There wasn’t a hugely thriving Dominican population in Logan Square. And every time that my family tried to go out to the island — literally every time we had a trip that we were about to plan, about to buy the tickets for, year after year, there would be something that would come up, almost always financially related. By and large, there was this constant idea that my relationship with the Dominican community was something I had to imagine. And then to run into this question of politics — as a kid you’re trying to conceptualize: What is a dictatorship? What is genocide? What happened to all the people who disappeared during the Trujillato? Those were deeply personal questions, not just because they were things that happened to my community, but because one of my abuelo’s main incentives for going to America was the understanding that Trujillo’s secret police was coming for him. He needed to make a decision. All of these disappearances — I am inches and luck away from being a completely different person sitting here talking to you, because if my abuelo disappears, I don’t exist.

Fantasy gives me an opportunity to bring together not only our communal myths, but also these personal myths that I had to build up around my relationship with being Dominican, and to play those things out. Fantasy allowed me to explore how power can affect and be inflicted upon a character, Pilar. And Pilar, over the course of the book, is finding her own power and being able to source that, not just in the way that I do as a person in day-to-day life — being able to think and imagine and hold things to be true about myself — but, as she comes to understand it, the actual ability to make those things manifest. I wanted that so desperately as a kid. I wanted so desperately for that to be tied to the magic that I knew that I came from, watching how my mother and her sisters interact with each other, the stories they would tell, this magical rhythm to the way that they spoke. I wanted so badly for there to be a book that captured the way that was magic, as much as the way that a dragon can be magic. No disrespect to dragons.

RS: I also think that in writing your book, you’re strengthening your bond to your Dominican roots, right? There’s a kind of magic in the act of writing.

JR: Yeah, absolutely. When we look at the rich history of Dominican writers — that’s one of the things that’s most exciting about right now, that we’re in this wonderful Dominican writer renaissance, Liz Acevedo, Gabriel Ramirez, Angie Cruz, Lorraine Avila. There are so many wonderful Dominican writers who are coming to the forefront. And of course there’s always Julia Alvarez. And Claribel Ortega — I couldn’t forget Claribel. There are so many wonderful Dominican writers doing stuff right now, it’s been cool to see, above anything else, how the act of writing has bonded me closer to them. And made me closer to my mom. It’s just been such a great experience.

RS: I do think it was pretty nervy to put Trujillo in literal league with the devil. That was a brave thing to do, because you could run the danger of explaining away his evil if you say he’s being controlled by a supernatural source.

JR: That was why it was so important to me to emphasize they were partners. This was a deal that went two ways. Trujillo’s allowing El Cuco to found a prison and make it the source of his power made him more fearsome. In so doing, that also helped Trujillo reify a lot of these myths that he built up around himself. There’s a whole shelf of books behind me that are just books about Trujillo. There are none, by the way, outside of In the Time of the Butterflies, about the Mirabal sisters — nothing nonfiction — that are written in English that I could find. It was very fascinating that most of the things I was able to learn about them I had to learn about through the book about the man who killed them. So much of reading those books was to understand that Trujillo had built up this mythos around him. I should have mentioned this in my fantasy answer — it is kind of hard to imagine doing a book around the impact of his regime that was only predicated on realism. He managed to convince people in his inner circle that he didn’t sweat! I was living in the DR earlier this year. It was February. It was eighty-something degrees. Lies. Lies and propaganda. All that to say that he had built up this idea of himself that he could see all, do all. People would disappear with no recourse, there’s no way to get them back. All of those elements are what allowed him to maintain power for so long. The idea that he and El Cuco are both these hollow figures, deeply evil but also needing each other — I was not trying to undermine the legacy of how evil his actions were, but to show they did not come from someone who was invulnerable. They came from someone who, like all dictators, needed the myth of himself.

RS: Why does that sound so familiar to us in the States today?

JR: I can’t put my finger on it.

RS: What do you think you’ll do next?

JR: A Pilar sequel is in the works — I am ninety percent certain I’m allowed to talk about that. It is the close of the duology. I’m in the edits for the first draft of it right now. It has been so fun and such a challenge. I’ve never had to close a series before — I’ve never written a series before. It’s Pilar’s first time on the island, and a lot of it is dealing with her relationship with the island at a diasporic level. What does this trip mean to her? Also along the way she’s starting to see storm clouds that no one else can see. There’s someone after her, but she can’t necessarily figure out who it is. There’s a lot that I can’t talk about — but it’s definitely been a joy to be working on it. I’ve got a couple of other middle-grade projects that I’m working on developing out the worlds for right now, and I’m really excited about those. There’s a lot that I’m really excited about. This is going to be a good decade for middle-grade and YA. I’m really happy to be part of it.

RS: How are you finding being a part of that as opposed to being in poetry?

JR: It’s been really fascinating. Like I said, I come from a slam background. Because you’re doing more one-off stuff, at events, you can read one piece and you’re good, whereas with nonfiction, fiction, you’re generally excerpting from your work, unless you have all the time in the world to read your book, in which case, great for you. In poetry, you see people publishing individually in different spaces, or if you’re more slam or orally oriented, you see people at open mics over time, and that’s how those relationships grow. Whereas I’ve found that for YA and middle grade, I’m generally able to make more contact and more community with folks after the project I’m working on has already been announced. Both of these are providing me with some really wonderful relationships — it’s just totally super-different. With fiction, I see people when their book is finished. With poetry, I see people throughout the process. I’ll see them at an open mic, and they’ll read something, and four months later I’ll see them at another reading, and they’ll read that thing, but also another thing, and there’s a theme coming together. It’s similar, but different.

RS: I think in slam poetry that process is as much a part of it as the actual text. With the book, you’ve got your book.

JR: There’s a process in poetry. With YA and middle grade, it’s very rare, in my experience, for people to be like, “I’ve got something in the chamber; let me read it to you.” Whereas with poetry, I generally see a lot more folks coming up and being like, “I’m kind of working on this thing; let me see what’s going on with that.” So it’s been fascinating going through it on that end.

RS: Welcome to the new club.

JR: I’m very excited. Thank you.

Sponsored by

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!