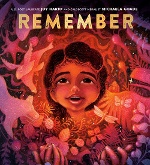

Michaela Goade Talks with Roger

To illustrate a picture book edition of Joy Harjo’s poem “Remember,” from her 1983 collection She Had Some Horses, Caldecott Medalist Michaela Goade faced several intriguing challenges, which we discuss below. I must say that the view of Alaska's Sitka Sound from Michaela’s studio is the finest Zoom background I've seen yet!

Talks with Roger is a sponsored supplement to our free monthly e-newsletter, Notes from the Horn Book. To receive Notes, sign up here.

Sponsored by

To illustrate a picture book edition of Joy Harjo’s poem “Remember,” from her 1983 collection She Had Some Horses, Caldecott Medalist Michaela Goade faced several intriguing challenges, which we discuss below. I must say that the view of Alaska's Sitka Sound from Michaela’s studio is the finest Zoom background I've seen yet!

Roger Sutton: Michaela, tell me how this project got to you, or how you got to this project.

Michaela Goade: Taking on this project was a no-brainer. Sometimes when you’re offered a text, there’s a lot of thinking through the pros and cons. Occasionally a manuscript will find you, and there’s no doubt. That was the case with this poem, which I hadn’t been aware of before. I know it’s been around for a long time and been through some unique forms already, so to become a part of Joy’s beautiful poem in a new form and for a new audience has been a special experience.

Michaela Goade: Taking on this project was a no-brainer. Sometimes when you’re offered a text, there’s a lot of thinking through the pros and cons. Occasionally a manuscript will find you, and there’s no doubt. That was the case with this poem, which I hadn’t been aware of before. I know it’s been around for a long time and been through some unique forms already, so to become a part of Joy’s beautiful poem in a new form and for a new audience has been a special experience.

Photo credit: Sydney Akagi.

RS: Isn’t that your job, as the illustrator?

MG: Of course. When you’re the illustrator of a picture book working with another author’s text, there is a unique alchemy that happens. At the end of the day, you end up creating something that never would have been possible if it were just you working alone. I’ll bring in my own influences. But because Native American culture isn’t a monolith, I often look to the author to ground the visual narrative. For example, in the case of We Are Water Protectors, I looked to Carole’s Ojibwe culture but also tried to represent a multitude because of what Standing Rock represented. For Remember, I leaned into the visuals and the stories and language in a much more personal way than I had in any other book written by an author from different Native Nation. It felt natural because the poem asks us to remember who we are and where we come from, and that’s what I was doing. Joy and I are from different generations, which I think is a neat conversation at play in this book, but also different geographies, different traditions, different cultures. I love the merging of all those elements.

RS: Can you describe what it’s like when you get that moment where you think, aha, here’s my starting point. How do you get there?

MG: Man, if I knew the answer to that, I would save myself a lot of time and frustration! It doesn’t always happen smoothly, to be honest. Sometimes you feel a bit lost for most of the project. For this book, I spent a great deal of time brainstorming and thinking through different starting points. At this stage, it’s creative detective work. I’m researching, taking notes and sketching, trying to connect dots and find common themes. My memorable and pivotal “aha!” moment came as I was mulling over the first few lines and trying to sort out how I might open the story and set the book’s tone. It felt so cosmic, primordial, and as a result — daunting! Joy asks the reader to first remember the sky and stars, and then to remember the moon, and lastly to remember the sun. I realized that the order in which she calls on us to remember those things — the stars, the moon, the sun — is the same order used in traditional Tlingit tales for our Raven creation stories, particularly how Raven brought light into the world. He first releases the box containing the stars, and then the moon, and lastly the sun. When I made that connection, I thought, aha, this is my sign. I’m going to root it in my own Tlingit culture. That felt exciting, but it’s something I hadn’t done before — using an author from another Native Nation’s text and pairing it with visuals inspired solely by my own cultural background. It was a little scary.

RS: How do you do that? Harjo’s poem isn’t abstract, but it’s very universal. You could have pictures from any culture. Carole Lindstrom’s text for We Are Water Protectors was fairly abstract. How do you turn the lack of visual cues into a narrative with illustrations?

MG: I think I gravitate toward those kinds of texts. I love how open they are for interpretation. We Are Water Protectors was rooted in actual historical events, so there was something I could anchor and research, something I couldn’t stray far from. But Remember is so wide open — brilliantly so! But as the illustrator, I recognized that a lot was going to fall to the art to make this a visually relatable and accessible narrative for children. I thought through many different paths. Maybe I could root it in Joy’s Muskogee Nation. Perhaps I could show a few kids from different corners of Indian Country, incorporating different Native Nations and thus hopefully increasing representation. But that felt intimidating, just for the sheer amount of research I would have to do. I am still an outsider to these communities that aren’t my own, so that didn’t feel totally right either. Joy’s poem was inviting me to remember my own origin story, and I felt like the art would need to rise to the occasion in terms of meaning and nuance. I ended up weaving bits and pieces of my life into the art — things I’ve learned and experienced on my own journey toward reclaiming my identity as a Lingít person and artist. I looked to our rich cultural traditions, our stories and language. I looked to personal memory, dreams, and adventures with my family. Ultimately, I hoped to speak to these cosmic themes in a very personal way and make a book that I would’ve loved as a little kid.

Courtesy of Michaela Goade.

RS: But then you still have to do all the work. It doesn’t emerge fully grown.

MG: Right! You’re doing a tough puzzle, and there’s that first move that helps you see the way forward. Of course, you still need to figure out the rest of the details. That’s sometimes where I struggle. I love big picture thinking and loose black-and-white sketches, so the actual painting stage is a time-consuming part of the process for me as I work to bring vision to paper. I never know what the final art is going to look like until the book is almost done!

RS: Was the text set, or was anything changed to turn it into a picture book?

MG: It was fairly set. I think they had to remove maybe one or two lines from the poem to make it fit the page count.

RS: Do you know how Joy Harjo feels about it?

MG: Well, she recently received her author copies and told me that upon first reading, she found herself in tears. That means the world to me! She was wonderful to work with. She wrote this poem decades ago, and it’s been published and presented in different forms over the years. A lot of authors might be more precious about their words, but Joy let me have creative autonomy. She was very open and receptive to my ideas every step of the way. That’s a great gift for an artist, not only to get a text that’s inviting, but also for the author to make you feel like this is your book too. To be welcomed as part of that process is always a gift.

RS: One thing that I think is brilliant about this book is the way you took a text with no specific cultural reference — not to Joy’s nation, not to my Irish Catholic background, not to any one thing — and you particularized it to your own Tlingit background. To me, it’s that individuality of your approach that allows me, who’s not Tlingit or Native, to say, “Oh, yeah, this is a book for me too.” It’s not just a book for someone from Joy’s culture or yours.

RS: One thing that I think is brilliant about this book is the way you took a text with no specific cultural reference — not to Joy’s nation, not to my Irish Catholic background, not to any one thing — and you particularized it to your own Tlingit background. To me, it’s that individuality of your approach that allows me, who’s not Tlingit or Native, to say, “Oh, yeah, this is a book for me too.” It’s not just a book for someone from Joy’s culture or yours.

MG: That’s always the goal, right? To speak to many different audiences. For the books that I work on, being able to speak to both Native and non-Native people is essential. I’ve found the saying — the universal is in the details — to be true and inspiring. When you lean into your own personal mythology, to what makes you you, the more heartfelt, powerful, and authentic your work comes across to the reader. This book speaks to huge all-encompassing themes, but in a personal way, because Joy is asking us to remember our own stories. With every book that I work on, I want Native children to leave the book feeling seen, celebrated, and inspired to explore their own stories. I also want to speak to non-Native children and inspire them to think about who they are and where they come from. The message at the heart of it is that we’re all human. We’re connected to one another and to our different places in the world. That theme is usually at the core of every book that I work on. It’s exciting to explore what that means in new ways from book to book. You make more progress in cross-cultural understanding and bridging boundaries, and I think that’s pretty important work.

RS: Because the book has a “here’s me; how about you?” implied invitation, you could have taken a more amorphous, We Are the World approach. I’ve seen books like that — you change cultures on each page. “This is how Chinese people look at this. This is how Indian people look at this.”

MG: There’s nothing wrong with that approach, but I don't feel it speaks to that deep human need for connection and belonging that I think we all yearn for, no matter where we come from. That’s one of the reasons why I ultimately didn’t choose to include different Native Nations in this book. I’m not from those Nations; I’m not going to know all the nuances and complexities that exist in those cultures. Even for the visual narrative for Remember, I leaned into a more personal experience, yet it’s not really a personal story. The narrative follows a young girl, beginning with this almost ancient primordial tone. Raven brings light to the world, and then we’re introduced to this young girl — we kind of drop in on her as she grows up. Her family drops into the illustrations too. I did try to retain a more universal story of her, getting more into the details of the things around her and the stories around her, versus getting into the nitty-gritty of her actual family life.

RS: You mention formline design in the afterword as the artistic style. What is that exactly?

MG: Formline design, which is also called Northwest Coast Native art, is an ancient, unique, and culturally significant art form that developed along the coast from what we now know as Southeast Alaska, through British Columbia, and into the Pacific Northwest regions. There’s so much meaning imbued in traditional formline. If you look at a totem pole, for instance, the designs used and the way it’s organized tells a story. The panels on traditional houses told a viewer who lived there, whose land you’re entering. Animal crests are very particular to certain clans, so when you see a particular crest in traditional regalia, you know exactly where that person comes from and who their people are. When I was thinking about how I could lend the illustrations more gravity to complement Joy’s powerful and important words, formline seemed like a way to do that.

Courtesy of Michaela Goade.

RS: What technical challenges were you presented with in trying to convey that?

MG: A lot! While I have received some training, I am by no means a formline artist. Traditional formline artists train for years, apprenticing with master artists to learn the craft. You can tell when you look at it. There’s so much balance and confidence in the positive and negative space. There’s protocol and hierarchy in how you compose a design; intentional relationships can be found within every aspect of the image, from the curves to the thickness. It’s very beautiful and complex. Each region has its own unique take on the art form. I’ve learned a little bit over the years here and there, but I’ve never felt confident enough to include much of it in a children’s book. It’s always been important to me that it never feel forced, especially as somebody who doesn’t work closely with formline. Alison Bremner, a talented formline artist and friend, was generous enough to be my formline mentor for this book. She’s an amazing artist, and she helped me refine the shapes and thicknesses of the lines. I know they’re not as perfect as they could be, but I tried hard with the hope that formline artists wouldn’t find it too off-putting! Of course, I’m bringing watercolor into it, so from the beginning I’m merging contemporary and traditional techniques. Joy’s poem talks about listening to the plants and the animals: “Remember the plants, trees, / animal life who all have their tribes, / their families, their histories, too. / Talk to them, listen to them. // They are alive poems.” I’ve never heard formline described as an alive poem, but that is, in my mind, what a lot of these designs are. It made a lot more work; I spent weeks trying to perfect the formline as best I could. I wanted the art to have the layers of meaning that I felt Joy’s text was calling for. I was proud to be able to include that. Formline isn’t right for every book that I work on but it felt right for this one.

RS: Your last three books are all very distinct from one another.

MG: Oh, thank you! That’s a goal of mine because I’m often exploring similar themes. Working with authors from different Nations definitely helps. There’s always something to learn! I’m often learning about new cultures and lands, making connections with the author and finding inspiration from their experiences. Trying new things to better represent the story is important, so that you can help make the best book possible. It keeps me on my toes, helps me feel engaged and evolving as an artist, especially because, like I said, the themes at the hearts of the books I’ve worked on can feel quite similar: land as central to identity, our connections to humans and non-human kin, our relationship to the world around us. How can I explore the importance of these ideas in different ways?

RS: But that’s also you, right? If you read a manuscript, or you read anything, you’re bringing yourself to that. What’s going to jump out at you are the things that matter to you.

MG: Yes, totally. These themes are important to me personally, so whether I’m aware of it or not, that’s what I’ll choose to anchor the visual narrative. That’s part of the joy when you are the illustrator, and again — that magical alchemy! It’s a creative puzzle that keeps you curious. It’s finding your story within the author’s words. As Remember reminds us, we all have our own powerful stories to share with the world, and that’s a beautiful thing!

Sponsored by

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!