Five questions for Nikole Hannah-Jones, Renée Watson, and Nikkolas Smith

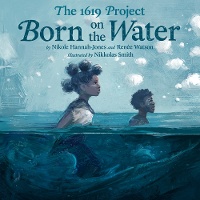

The 1619 Project, developed by journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones, with writers from the New York Times and the New York Times Magazine, debuted in August 2019, marking “the 400th anniversary of the beginning of American slavery.” The project’s goal: “To reframe the country’s history by placing the consequences of slavery and the contributions of black Americans at the very center of our national narrative.” Hannah-Jones won the 2020 Pulitzer Prize for Commentary for her work. Now she teams with CSK Author Award winner Renée Watson and illustrator Nikkolas Smith for The 1619 Project: Born on the Water, a picture book in verse about one family’s ancestry — and many families’ history.

The 1619 Project, developed by journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones, with writers from the New York Times and the New York Times Magazine, debuted in August 2019, marking “the 400th anniversary of the beginning of American slavery.” The project’s goal: “To reframe the country’s history by placing the consequences of slavery and the contributions of black Americans at the very center of our national narrative.” Hannah-Jones won the 2020 Pulitzer Prize for Commentary for her work. Now she teams with CSK Author Award winner Renée Watson and illustrator Nikkolas Smith for The 1619 Project: Born on the Water, a picture book in verse about one family’s ancestry — and many families’ history.

1. How did this project — and this team — come about?

Renée Watson: I was invited to co-write The 1619 Project: Born on the Water by Namrata Tripathi, our editor, and Nikole Hannah-Jones. We had an initial meeting to talk about the vision of the book, and right away I knew I wanted to be a part of it. First, because I respect Nikole’s work so much; and also because so many educators and parents reach out to me asking for resources to help them talk about slavery in an age-appropriate way. So, I was excited about the possibility and knew immediately that there are families and school communities who want and need a book like this.

Renée Watson: I was invited to co-write The 1619 Project: Born on the Water by Namrata Tripathi, our editor, and Nikole Hannah-Jones. We had an initial meeting to talk about the vision of the book, and right away I knew I wanted to be a part of it. First, because I respect Nikole’s work so much; and also because so many educators and parents reach out to me asking for resources to help them talk about slavery in an age-appropriate way. So, I was excited about the possibility and knew immediately that there are families and school communities who want and need a book like this.

Nikole Hannah-Jones: When The 1619 Project first published, and ever since, parents have been asking whether we were going to turn the project into something they could share with their young children. So, from the moment we first began talking about turning The 1619 Project into a book, we knew part of that expansion had to include a children’s book.

Nikole Hannah-Jones: When The 1619 Project first published, and ever since, parents have been asking whether we were going to turn the project into something they could share with their young children. So, from the moment we first began talking about turning The 1619 Project into a book, we knew part of that expansion had to include a children’s book.

I had never written a children’s book and was very keen to partner with an established children’s book author. Kokila recommended Renée. I had long admired her writing and then read everything she’d written that I had not yet read. We met over Zoom and immediately hit it off, and I knew Renée was the perfect partner.

Kokila also sent along a list of potential illustrators and their work samples, and when we saw Nikkolas’s beautiful art, the entire team agreed that he had what it took to bring this book to life.

Nikkolas Smith: I was contacted by Kokila in 2020, and when the team let me know who the authors were and the subject matter, I was immediately on board. It’s such an immense honor to be asked to illustrate a dream project like this, especially one that I have such a strong connection to, being a Texas-born descendant of enslaved people from Central West Africa. After reading the amazing poetry by Nikole and Renée, I painted a few concepts for the book cover and shared them with the group. From that moment on, we knew this team was a great match, and the book came together pretty seamlessly.

Nikkolas Smith: I was contacted by Kokila in 2020, and when the team let me know who the authors were and the subject matter, I was immediately on board. It’s such an immense honor to be asked to illustrate a dream project like this, especially one that I have such a strong connection to, being a Texas-born descendant of enslaved people from Central West Africa. After reading the amazing poetry by Nikole and Renée, I painted a few concepts for the book cover and shared them with the group. From that moment on, we knew this team was a great match, and the book came together pretty seamlessly.

2. To distill the information into picture book form — and in verse! — must’ve been a challenge. What was that process like?

RW: One of the reasons we wrote the book in verse is to give each moment its own container and to help break down such a big story into vignettes to make it manageable for young readers. At the center of our writing process was the commitment to not only focus on the horror but on the people’s humanity. Before we started writing, Nikole and I talked about what we wanted children to feel while reading the book. With each verse, we wrote toward that goal of wanting Black American children to feel seen, validated, educated, and proud. Craft-wise, we determined that repetition would be a way to both anchor our writing and also reinforce themes in the story for the reader. I think having repetitive phrases helped keep our writing in sync.

3. Nikkolas, what type of research and source materials did you use?

NS: There are so many parts of this book related to Ndongo where I had an opportunity to trace the roots of Black joy, ingenuity, education, and fashion back to its most traditional forms. I studied many Angolan/West African history books and referenced a lot of Ouidah, Benin, and Congolese culture — from festive-wear, to religious rituals, to commerce, to astronomy, and more. Nikole’s original 1619 work was also very helpful reference material as I was creating visuals pertaining to resistance and nation-building in the second half of the book.

4. In both text and pictures, the book blends specificity about this family’s intergenerational story with observations about many who were “born on the water.” How did you choose where to place focus?

4. In both text and pictures, the book blends specificity about this family’s intergenerational story with observations about many who were “born on the water.” How did you choose where to place focus?

RW: Because of Nikole’s thorough research, we had a lot of information to pull from when writing the picture book. It was important to balance the personal story of the main character and anchor her to an actual place and language to show the specificity of her identity while also showing her connection to the broader story. Nikole and I were intentional about layering the story with the brilliance, joy, and resilience of the enslaved people. We made sure to focus on moments of history that showed their ingenuity and their will to survive what they were not meant to survive.

NHJ: I agree with Renée. Having both specificity around a single family and people, since we rarely see the specifics of Black American families before they came to America, and a larger story about Black Americans as a people was critical for us. Humanity is in the details, and too often the stories of enslaved people do not get into the individual lives — the pasts and stories and relationships before slavery. That’s why it was so important for us to tell a story that was both broad and personal.

NS: Because so many Black Americans have the same questions about ancestry, and the same connection of the Middle Passage, I felt that it was necessary to let the imagery branch out to reflect a multitude of African features that Black Americans see in themselves today. I find it fascinating that there are tribes in Africa that I can visit today who share specific facial features with me and my family. Every Black person in America can relate to this possibility, and I want each to see a piece of themselves in Born on the Water.

5. Much of the book takes place in the past, but with a strong through line to today. What’s something you hope young readers come away with?

RW: I hope all readers come away from the book feeling empowered to ask questions about their personal history, about American history. I hope they realize that they have a legacy of freedom fighters, artists, and change-makers who left an example of how to stand up for justice. For Black American children, specifically, who may have felt disconnected from their roots, I hope the verses in Born on the Water make them feel seen, validated, and inspired.

NHJ: I do not have much to add to what Renée said here because I agree with it all. I would just emphasize that I especially hope Black children who descend from American slavery will take from this a sense of enduring pride in an origin story that is uniquely ours and of which we should have absolutely no shame.

NS: My hope is that young readers will see a strong and brilliant people reflected in my paintings. I want young Black readers to understand that they can look back on their African ancestry with pride and know that their lineage does not begin with enslavement. I want readers from ages five to one-hundred-and-five to always remember that they can courageously hold America to its promise of justice for all, in the spirit of resistance that countless Black Americans have demonstrated. It is my hope that these paintings will be a constant reminder of that call to action.

From the October 2021 issue of Notes from the Horn Book.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!