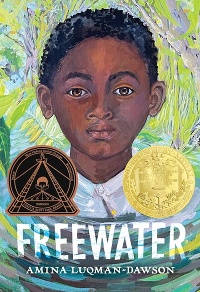

2023 Newbery Medal Acceptance by Amina Luqman-Dawson

I’ll begin with gratitude. Thank you to the Newbery committee for recognizing Freewater. You read my work, connected with it, and judged it worthy, regardless of my debut status. To Laura Schreiber, the editor who plucked Freewater from an ever-flowing river of manuscripts. Laura immediately had vision and excitement for it. Thanks to James Patterson and JIMMY Patterson Books for beginning my journey.

I’ll begin with gratitude. Thank you to the Newbery committee for recognizing Freewater. You read my work, connected with it, and judged it worthy, regardless of my debut status. To Laura Schreiber, the editor who plucked Freewater from an ever-flowing river of manuscripts. Laura immediately had vision and excitement for it. Thanks to James Patterson and JIMMY Patterson Books for beginning my journey. To publisher Megan Tingley, executive director of school and library marketing Victoria Stapleton, and Little, Brown Books for Young Readers — you have been the perfect landing home for Freewater. You have treated me and Freewater with a care and respect that were essential to this extraordinary outcome. Thank you.

To Alexandra Hightower, my editor. Fate brought us together. Freewater was meant to be in your capable hands. To Kathi Appelt and to We Need Diverse Books, the wonderful organization that brought us together. Thank you, Kathi, for treating me as a fellow writer from day one. I appreciated you as a mentor, and I cherish you even more now as a friend. Thank you to my agent, my advocate, Emily Van Beek at Folio Jr. Your phone call changed my life. I am forever grateful to my cheerleading family: to my mother, who planted the writing seed in me; to my son, Zach, for inspiring me. To my husband, Robert, my rock and most ardent supporter, who believed without question that this was possible.

It also feels appropriate, given that I am before an audience of librarians, that I thank my favorite childhood librarian at Leland R. Weaver Library in South Gate, California. She was fierce. She was Black, Afro-Latina to be precise. She’d speak to me in English and in the next breath turn to another child and speak in Spanish. It was like magic. I wanted to learn that trick. She wore two-piece suits with three-inch heels that could be heard rapidly swishing on the library carpet. There’s been some debate in my family as to her name. I’ve been saying it was Ms. Carmelita, my mom says it was Ms. Marlena. But I rarely had to say her name because she would just appear during our library visits, excited, as if we were in a Prada or Louis Vuitton store on Rodeo Drive and I was her customer. What are we looking for today? she’d ask, then pull a book that she thought might suit my taste. And if I even slightly crinkled my nose in boredom or disapproval, she’d say, Oh! Not that one, and off we went to another book. Then she would disappear, and I would be left to explore.

I learned from her. Certainly, not what to read. Instead, she taught me that I had the power to read anything I wanted. Regardless of what anyone thought, even her, what I read was my choosing. That’s what makes the library sacred.

It’s why in today’s book-banning climate, claims of librarians “grooming” children are utterly ridiculous and dangerous. Any child searching the stacks of a library is there for the freedom to choose. It’s that freedom that scares book banners — not librarians. I thank my childhood librarian and I thank today’s librarians, who have been put on the front lines of this book-banning assault.

I’ve been asked several times whether I worry about the impact of book banning on Freewater. I find it an interesting question. Part of the danger of this book-banning assault is that it skews and distorts discussion. A ban implies that our children’s lives have been awash in literature and learning about the banned topics, such as LGBTQIA+ and African American experiences (in my particular case) and the nation’s history of slavery. It tilts discussion away from our historical shortcomings and forces us to fight for the bare minimum, the right to exist — to merely have our books on a library shelf or in a classroom.

I’ve been asked several times whether I worry about the impact of book banning on Freewater. I find it an interesting question. Part of the danger of this book-banning assault is that it skews and distorts discussion. A ban implies that our children’s lives have been awash in literature and learning about the banned topics, such as LGBTQIA+ and African American experiences (in my particular case) and the nation’s history of slavery. It tilts discussion away from our historical shortcomings and forces us to fight for the bare minimum, the right to exist — to merely have our books on a library shelf or in a classroom.

When I contemplate how Freewater will be received, I think of it less about book bans and more about the people I had in mind while writing it. The solitary Black child sitting in a classroom with prickly hairs on their neck as they listen to a lesson on slavery. About the teacher feeling awkward and unsure standing before students. About Black moms and dads, like myself, living our busy lives with a nagging thought that we need to find a way to share these stories with our children. I think of my childhood self, fearing this topic regardless of how important I knew it was. I think about all American children. I think about the discomfort and avoidance adults often carry regarding the nation’s history of slavery and the unspoken ways we transmit those feelings to our children.

But our response to this topic is not by chance. We are not fully to blame. The nation’s system of enslavement was engineered so that I wouldn’t be here to speak about it nor have you here to listen. Slavery’s engineers and supporters were resolute and complete in having the voices of enslaved African women, men, and children erased from history. If you feel a disconnect, a blank space, a silence between you and the enslaved people who helped build this nation, know that this feeling is by design. Enslaved people and even free Blacks who lived in the South were banned from learning to read and write. No quill and ink were allowed to enslaved people to note the day’s horrors, gifts, love, and loss. As a writer, each time I consider this, I find it almost unfathomable. No journal could be kept, nor letter written to share one’s life experiences. To be caught attempting to learn to read often meant physical harm or even sale away from one’s family.

From the universe of stories held by over ten million enslaved people, precious little survived. The stories reside within the families of their descendants through oral traditions. There are recorded narratives, memoirs of those who escaped and survived and more. Each word, each story is precious. I am forever grateful to the elders, the historians, and artists who have maintained and shared this history. Without them I would not be here. Still, what of the millions of voices lost and silenced?

Let’s not forget that within the silence, engineers of slavery placed distortions about who enslaved people were — lazy (which I find particularly incredible), of lower intelligence, and more. These lies and distortions were so powerful that they still seep into how their descendants and all Black people are cast today.

So, what do we do with this mess of a legacy surrounding slavery? A legacy of silence, distortion, lies, feelings of disconnect and fear. We destroy it. We leave a better legacy behind for our children. Never fear, there’s good news. Although ugliness and greed may have built this, beauty and art can end it. At least it can help. I’ve been asked more than once why, given the fascinating history behind Freewater, I hadn’t chosen to write a nonfiction book instead. I’m a storyteller. I lured the reader in with a lesser-known history — maroons. Enslaved people who escape and manage to live secret and clandestine lives in the wilderness. It’s super-cool history. However, I’m really in the business of restoration — restoring voices of silenced enslaved people, injecting life and experiences where they have been erased. In Freewater, it’s the children who really do that work. Little kids, both formerly enslaved and free, each with their own personalities and ways of seeing the world. We hear their hopes and fears and watch them make mistakes, and we listen to them tell their stories. Their journey seeps in between the cracks of our fears and discomfort. And creates a bridge across disconnected space.

Between you and me, my hope is for something even grander. It’s for the nation’s enslaved ancestors to find a place in our historical imagination. Exalted figures live in our historical imagination. Despite how problematic some of them may be, they are embedded in us. You may not even know they’re in you until I mention them. The cowboy — instantly, we see John Wayne. Settlers of the West — we see Laura Ingalls Wilder in her “little house on the prairie.” The princess. We know what she looks like. We know she lived long ago in a place far, far, away. These images are so powerful that although they live in our past, we still assign value to them today. The cowboy is still heroic, the princess is still who little girls want to be for Halloween. It’s beyond time to expand our imaginations, to be more thoughtful and inclusive. What of the enslaved child? Our historical imagination is where my enslaved characters are meant to reside. In a place where instantly, when we think of them, we know to be inspired and awed by their role in history. That is the goal. That’s the hope.

So, I return to the Newbery committee with my deepest gratitude. Today, we live in a space where, again, we are witnessing literary voices, particularly Black and LGBTQIA+ voices, being erased from our libraries and classrooms. I believe Freewater is the right book at exactly the right time. It’s a book about restoring voice and connection to those who have been silenced and erased. What’s more befitting than shining a light on a work that shows that this struggle is not new, and this assault can be defeated? Thank you.

Amina Luqman-Dawson is the winner of the 2023 Newbery Medal for Freewater, published by JIMMY Patterson Books, an imprint of Little, Brown and Company. Her acceptance speech was delivered at the annual conference of the American Library Association in Chicago on June 25, 2023. From the July/August 2023 issue of The Horn Book Magazine: Special Issue: ALA Awards. For more speeches, profiles, and articles, click the tag ALA 2023.

Single copies of this special issue are available for $15.00 including postage and may be ordered from:

Single copies of this special issue are available for $15.00 including postage and may be ordered from:

Horn Book Magazine Customer Service

hbmsubs@pcspublink.com

Full subscription information is here.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!