In Memoriam: The Great Ed Young

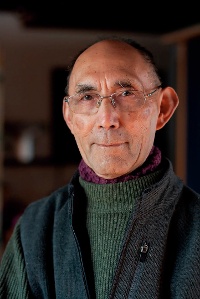

The first time I saw the great Ed Young (1931–2023), I felt awestruck by his presence. Tall, angular jaw, prominent ears that looked like they listened. He exuded calm and grace. There was often a deep chuckle ready to break out, as if, to him, life itself was wry.

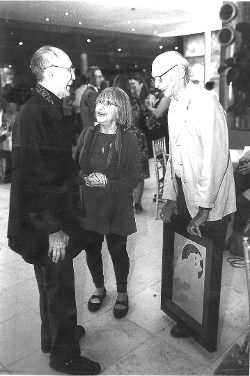

The first time I saw the great Ed Young (1931–2023), I felt awestruck by his presence. Tall, angular jaw, prominent ears that looked like they listened. He exuded calm and grace. There was often a deep chuckle ready to break out, as if, to him, life itself was wry. [Photo © Gina Randazzo]

The first time I saw the great Ed Young (1931–2023), I felt awestruck by his presence. Tall, angular jaw, prominent ears that looked like they listened. He exuded calm and grace. There was often a deep chuckle ready to break out, as if, to him, life itself was wry. [Photo © Gina Randazzo]

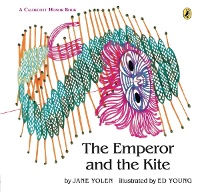

I first met Ed at a New York Times Best Illustrated luncheon in the late 1980s, which he was attending with his Philomel art director Nanette Stevenson. This esteemed creator, first published by Ursula Nordstrom at Harper & Row and then mentored by Philomel founder and editor in chief Ann Beneduce, had created several memorable picture books by the time I joined the company in 1985. One written by Jane Yolen, the paper-cut masterpiece The Emperor and the Kite, had won him the first of his two Caldecott Honors in 1968. I was awed by his presence and wondered, as the person who was slated to take Ann’s place when she soon retired, what I could bring to him and his books that he didn’t already have.

As editor, Ann had international as well as national outreach during her over twenty years at World Publishing, then Crowell, then Philomel. Her professional relationships with her artists — including Eric Carle, Tasha Tudor, Mitsumasa Anno, and Ed Young — were legendary. I, on the other hand, at that time was not even a professional editor. I was a writer, albeit a published writer of picture books, and a teacher, with perhaps an innate but not trained sense of design. I didn’t kid myself: I had a lot to learn.

As editor, Ann had international as well as national outreach during her over twenty years at World Publishing, then Crowell, then Philomel. Her professional relationships with her artists — including Eric Carle, Tasha Tudor, Mitsumasa Anno, and Ed Young — were legendary. I, on the other hand, at that time was not even a professional editor. I was a writer, albeit a published writer of picture books, and a teacher, with perhaps an innate but not trained sense of design. I didn’t kid myself: I had a lot to learn.

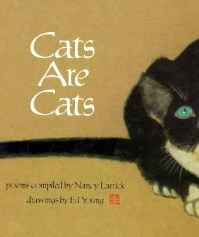

The manuscript for Cats Are Cats, an anthology of cat poems gathered by the respected librarian Nancy Larrick, came across my desk shortly after Ann left the company. I bought the manuscript, feeling that Ann would have, and knowing that Ed Young could do a beautiful job of illustrating it. His longtime art director, Nanette, and designer Martha Rago agreed, and they each poured their own artistry into the book to wonderful effect.

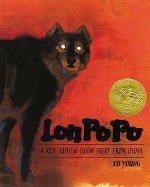

After the success of Cats Are Cats, we were searching for another project for Ed. He had previously illustrated stories written by other people, including Ai-Ling Louie, who wrote Yeh-Shen: A Cinderella Story from China. One day I held Yeh-Shen, with its powerful framed illustrations, and asked Ed: do you know other Chinese tales that you yourself could tell? As masterful as he was in illustrating stories someone else had written, he had not yet written one himself. I shared my confidence that day that he could do it. I had received handwritten notes from him and listened to him speak. Why not select and adapt his own tale, giving it the cadence, rhythm, and pacing of his own storytelling voice? This felt like a turn in the road for Ed and for our new artist/editor relationship, and it undoubtedly prepared us for work on his 1990 Caldecott Medal–winning Lon Po Po: A Red-Riding Hood Story from China.

After the success of Cats Are Cats, we were searching for another project for Ed. He had previously illustrated stories written by other people, including Ai-Ling Louie, who wrote Yeh-Shen: A Cinderella Story from China. One day I held Yeh-Shen, with its powerful framed illustrations, and asked Ed: do you know other Chinese tales that you yourself could tell? As masterful as he was in illustrating stories someone else had written, he had not yet written one himself. I shared my confidence that day that he could do it. I had received handwritten notes from him and listened to him speak. Why not select and adapt his own tale, giving it the cadence, rhythm, and pacing of his own storytelling voice? This felt like a turn in the road for Ed and for our new artist/editor relationship, and it undoubtedly prepared us for work on his 1990 Caldecott Medal–winning Lon Po Po: A Red-Riding Hood Story from China.

* * *

As I came to understand, Ed’s storytelling art had an inherent sense of play, of puzzle, of surprise, all of which he brought to that first collaboration of ours, Cats Are Cats, and continued throughout our work. (An earlier Philomel book, Bo Rabbit Smart for True: Tall Tales from the Gullah by Priscilla Jaquith and illustrated by Ed, may have been the first time I fully recognized that spirit in play.) I titled my 2011 Barbara Elleman Research Library (BERL) Lecture at The Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art “The Picture Book as an Act of Mischief,” and that is what I discovered in Ed Young and his art: he was a mischief maker.

He had played on the rooftop of his childhood Shanghai home with his two brothers, creating whole games in imaginary worlds. His U.S.–educated engineer father had played with his sons and daughters, teasing and puzzling with them. From Ed’s childhood, from his relationships with his brothers and sisters, from the way he lived, traveling as a young man from Hong Kong to Los Angeles to Chicago to Manhattan, always taking new life into himself, whether attending school to be an architect, or working in advertising, or sketching animals in Central Park, he was into artistic mischief. It gave him the opportunities for his art that he wanted.

Ed welcomed his editors — even new ones — into his workspace, the second floor of the wood-beamed barn behind his Hastings-on-Hudson, New York, house. After climbing the ladder into this space, I was awed by the objects stacked in barrels, crowded onto shelves, “throwaways” gathered in his studio for reasons Ed would not even know sometimes for years to come: scraps of wrapping paper, cardboard sheets, discarded metal. Ed was frugal, from his difficult, sometimes wanting years in China, but these objects were not throwaways in his eyes. They were his paintbox of colors and textures.

* * *

Lon Po Po, which features three Red Riding Hoods — Shang, Tao, and Paotze — rather than one, was the perfect playground for him artistically and for him to tell his first authored story. The book’s creators were a triumvirate. Nanette, the gifted art director, would partner with him on the illustrations and design. But I had a new responsibility: if Ed was going to believe in his voice, I had to encourage his using it, then protect and value it. I suggested that he take the version of the story he had found and rewrite it on a piece of paper in his own words. I wanted him to catch the lilt and nuance of his own Chinese words and expressions in his retelling. I could hardly wait to “hear” his story! The result was astounding. It reflected Ed’s newfound and confident voice.

Lon Po Po, which features three Red Riding Hoods — Shang, Tao, and Paotze — rather than one, was the perfect playground for him artistically and for him to tell his first authored story. The book’s creators were a triumvirate. Nanette, the gifted art director, would partner with him on the illustrations and design. But I had a new responsibility: if Ed was going to believe in his voice, I had to encourage his using it, then protect and value it. I suggested that he take the version of the story he had found and rewrite it on a piece of paper in his own words. I wanted him to catch the lilt and nuance of his own Chinese words and expressions in his retelling. I could hardly wait to “hear” his story! The result was astounding. It reflected Ed’s newfound and confident voice.

The combination of his sense of play in art and the subtle choice of words that partnered with his translation created a remarkable book in Lon Po Po — and a remarkable dedication by Ed. “To all the wolves of the world for lending their good name as a tangible symbol for our darkness.” He introduces the wolf traditionally enough at the beginning, its silhouette a living landscape of a predator, then bookends this silhouette at the end of the book — same landscape, same wolf, now battered and defeated by the three Little Red Riding Hoods.

But there is an ambiguity to Ed’s wolf. A reader can best sense this when the three Red Riding Hoods climb a tree so they can pluck ginkgo nuts to tempt the wolf now pretending to be their grandmother, their Po Po:

Now the children pulled the rope with all of their strength. As they pulled they sang, “Hei yo, hei yo,” and the basket rose straight up, higher than the first time, higher than the second time, higher and higher and higher until it nearly reached the top of the tree. When the wolf reached out, he could almost touch the highest branch.

But at that moment, Shang coughed and they all let go of the rope, and the basket fell down and down and down. Not only did the wolf bump his head, but he broke his heart to pieces.

I could hear Ed’s voice.

Ironically, in the art, the girls become the wolf themselves as Ed turns branches of the tree, then the bucket they are carrying to hold the ginkgo nuts, into the predatory eyes of the wolf, the trunk of the tree his long nose. Suddenly, to the reader, the threat appears to be coming from the wolfish girl-laden tree itself!

Ed had a voice, he had the words, undeniable artistic mastery — and he always had an idea you could believe in. For Seven Blind Mice, he returned to his studio of found objects to tell a witty version of the Indian fable “The Blind Men and the Elephant.” There is an understated quality to his text, as seven colorful and rambunctious mice scurry over parts of a curious “something” that turns out to be an elephant, allowing the tale to end with a “mouse moral”: “Knowing in part may make a fine tale, but wisdom comes from seeing the whole.”

Ed had a voice, he had the words, undeniable artistic mastery — and he always had an idea you could believe in. For Seven Blind Mice, he returned to his studio of found objects to tell a witty version of the Indian fable “The Blind Men and the Elephant.” There is an understated quality to his text, as seven colorful and rambunctious mice scurry over parts of a curious “something” that turns out to be an elephant, allowing the tale to end with a “mouse moral”: “Knowing in part may make a fine tale, but wisdom comes from seeing the whole.”

The handsome story, supported by Ed’s brilliant design, was extraordinarily whole in itself: poignant and resonant with simplicity. Once again, in 1993, he won a Caldecott Honor. He wrote of the telling in this book: “A Chinese painting is often accompanied by words. They are complementary. There are things that words do that pictures never can, and likewise, there are images that words can never describe.”

Do I believe using his own voice changed Ed’s use of and belief in words? Yes, I do. He seemed to grow comfortable writing about patches from his life, and he often chose books to illustrate, such as Wabi Sabi by Mark Reibstein, because of the spare, haiku-like rhythms. I contend that because he had begun to write stories himself, he understood words more intimately both in writing and reading.

* * *

The relationship between artist and art director is fundamental in the creation of a fine picture book. What, then, is the colleagueship between artist and editor? The editor, always looking for the original and appropriate story to publish, runs alongside the artist in search of the powerful story. In Ed’s case, the artist looking for the “found” material in his world includes words in that search; resonant words that reflected their “now” but that retained the echoes of earlier stories, and for him, extraordinarily rich Chinese culture.

|

| At the 2017 Carle Honors Gala: Ed Young, Patricia Lee Gauch, and Gauch's husband, Ron, holding art gifted by Ed. Photo credit: Johnny Wolf |

The world of Ed Young may have begun on the rooftop of his Shanghai house, in the world of his play, but it grew. He allowed it to grow, he encouraged it to grow. He chose friends and poets and family who understood his play. He understood the rich publishing partnerships that had been created in making a book and was grateful for them for a lifetime.

At the 2017 Carle Honors Gala, where he was honored as the artist of the year, presenter Jack Gantos described Ed’s work: “He consistently brings an eye for beauty, integrity, and innovation, and sets an inspiring example for young artists through his books.” To which Ed, standing at the podium thankful for these words and surrounded by the publishing audience, said, “I had no idea what I would talk about [tonight], except to thank the people who brought me here.” Being honored himself, it was two editors whom he, in turn, chose to honor. Both Ann and I were there that night. We were surprised, delighted, never forgetting for a minute that the only artist being honored by the annual Carle award in the room was the great Ed Young, the creator of books for all ages — art and words — bridge to his Chinese culture, who brought an “eye for beauty, integrity and innovation” in story to the world of children’s books. The prince. The master.

From the March/April 2024 issue of The Horn Book Magazine.

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!