Tricia Elam Walker and Ekua Holmes Talk with Roger

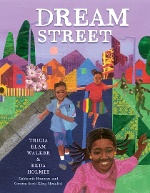

Cousins and friends growing up together in Roxbury, Massachusetts, Tricia Elam Walker and Ekua Holmes celebrate community in Dream Street.

Talks with Roger is a sponsored supplement to our free monthly e-newsletter, Notes from the Horn Book. To receive Notes, sign up here.

Sponsored by

Cousins and friends growing up together in Roxbury, Massachusetts, Tricia Elam Walker and Ekua Holmes celebrate community in Dream Street.

Roger Sutton: It looks to me like this book is literally a dream come true.

Ekua Holmes: Absolutely.

Ekua Holmes: Absolutely.

Tricia Elam Walker: It truly is, because Ekua and I had been talking for a while about trying to do something together, but nothing had materialized. She said to me, “Do you want to look at some of my collages and see what you can do with them?” At first, I was a little bit daunted, because I’m used to figuring out what the story is out of my own head. But I was able to see the stories within her work, because she’s a storyteller. That’s how we created Dream Street. There were collages of different people doing different things, and it all came together — these were people who lived on this wonderful street, one of those streets that reminded us of the way we grew up. She can take it from there.

EH: Much of my work is about growing up in the neighborhood that we grew up in, honoring the people who nurtured us as children, whether it’s the Sunday school teacher, the librarian, or the lady next door. There were characters like that in our life growing up who we appreciated and had fun with and laughed with. To see it all come together in this beautiful story that Tricia created inspires me.

RS: What was it like for each of you to give up part of the control of a book to another person? As an author, you have to leave room for the illustrator. As an illustrator, you have to not crowd out the author. How do you negotiate that?

EH: I trust Tricia and love her — she’s my cousin! Something she does that I find interesting is in naming her characters. They always have interesting names, and sometimes I’m like, “Hmm, I don’t know if I’m feeling that name.” But she understands the characters in a literal way. We were able to exercise that in this project.

TEW: And Roger, you should know, some of those names correspond to people who mean a lot to us. For instance, the little baby in the arms of one of the characters is named after Ekua’s granddaughter, Song. The librarian is named after my mom, Barbara. We worked together on that, wanting to make this book very heartfelt and meaningful to both of us.

RS: I loved when the librarian told the boy that he could be a librarian. Because that was me — I wanted to be one. I’m the same age as Ekua. I don’t know how old you are, Tricia, and I’m not going to be rude…

TEW: I’m just a year older.

RS: So we’re all around the same age. I was growing up not five miles away in Dedham while you guys were growing up in Roxbury. To us it was a different world. Boston, the city.

TEW: Right.

EH: And that’s interesting, Roger, because so many professions have various things associated with them. It’s great to be able to dispel one of those myths by telling this little boy, “Of course you can be a librarian!” I hope that will inspire some other young man who reads the book.

TEW: I often hear about children who were told they couldn’t be a certain thing, either because they are Black or because they are a girl or because they are a boy. It’s time for this to stop.

RS: The book does a great job of encouraging the reader to think: Who do I know, and who could I be like, in my neighborhood, on my Dream Street?

EH: That’s what we want.

RS: It gains because it’s so specific. The fact that everybody does have a name makes them feel like real people. Then the reader thinks: I have real people in my life too. Who’s on my street?

TEW: In the artwork they might see someone they know or someone who looks like their aunt or their grandmother. It could happen through the names: “I have an Aunt Sarah.” It could happen through their profession. A family of five boys. A little girl named Song. There are so many ways for readers to relate to the characters. What is your Dream Street? How is your Dream Street described? Who lives on it?

EH: Is it an actual street, or is it something in your imagination, or something that just lives inside you? I really like the idea that we captured ourselves in there. Our dream was in the dream of this book, and here it actually is.

RS: I have to say, parenthetically, I’m really loving to hear from you both the Boston pronunciation of aunt.

EH: I know, people say “ant,” don’t they?

TEW: When I hear people say “ant,” that doesn’t sound right to me. I guess it is a Boston thing.

RS: How close did you live to each other growing up?

EH: One and a half streets, initially, and then Tricia’s family moved another block away, so two and a half streets.

TEW: We spent lots of afternoons together after school. We didn’t have computers, cellphones, or those kinds of distractions. We could hardly watch television. We were very fortunate in that we had time to imagine and be creative and make these worlds up. Ekua — I can just picture her now, her little self, finding things that I would otherwise think were just junk or something to be thrown away and making creations out of them. Writing down conversations and making up characters — we were doing that at a young age. I remember telling my mom I wanted a story of mine to open like a real book, so she showed me how to sew the pages with neon thread. We were doing these things together, and then we branched off and did other things in our professions for a while, until we came back to our love and our art.

EH: I was asked this question on a panel: “What was the first book with African American characters that you read?” I thought about it and realized it was a book that I wrote myself, about my best friend in school. And Tricia had written a book about a dancer. Our first books were of our own making and our own imagining, which I think is kind of cool.

RS: Do you place this Dream Street in any particular space and time?

RS: Do you place this Dream Street in any particular space and time?

EH: That’s a very good question. I like to think that it transcends time, and space, for that matter, because I feel like there is a Dream Street in each of us. We can create a Dream Street wherever we are by becoming people who follow their dreams or help others. We all have that capacity.

TEW: And I think both of us do that in our work with and for young people. Helping them see they can have similar dreams or figure out their own dreams.

EH: It means a lot, just to have a word of encouragement. In the world still today, there are people who are telling children that they can’t or that they never will. We have to counteract that.

TEW: I hear those stories all the time and I’m always appalled. "A teacher told you that? What?!"

RS: Ekua, you’ve never left Roxbury as a home?

EH: I left for ten months to go to graduate school, and I came running home because I love Roxbury.

TEW: She sure did. Roger, she talked about leaving, and I’m like, "Uh-uh. That’s not going to happen."

EH: Everything I need is in Roxbury. Everything I’ve ever needed is in the city. I can travel the world through my illustrations, through books, and feel just as comfortable in my armchair doing those things.

RS: I’ve realized the only transportation I need is the 39 bus. I live in Jamaica Plain, and it goes everywhere I want to go: museums, Symphony Hall, my office. It’s perfect. Never need to leave.

TEW: What you said, Ekua, reminded me of something about my mom. Like I said, she was a librarian, and she would sit and read — she loved children’s books. Since she always wanted us to read, at first it felt like a punishment because there were other things we couldn’t do, like watch TV. But when I really got into it, I realized I was transported to other worlds, other people’s lives, different places. It expanded my imagination and made me want to do that same thing for readers.

EH: If I remember correctly, Tricia, there was a time when you didn’t have a television in your house. It was unusual — everybody had one in the sitting room, and the fathers controlled what was being watched. But your family didn’t have a TV in the early days.

TEW: That’s right. I had friends who had TVs in their bedrooms, and I thought, Oh my god, that’s wonderful. And my mother was like, "That’s never going to happen, ever."

RS: It’s like the one kid on the block who had a color TV. We couldn’t afford it, but there was always one kid.

TEW: Yeah. We wrote things, we wrote plays. My brother was very into theater and making costumes, and we’d make costumes and act out plays. Sometimes we went to the nursing home…

EH: Yes. And we’d recite poems and sing songs for the people in the nursing home.

TEW: Nowadays there’s a lot of talk in the academic community about service learning. I tell people that serving others was just a part of how we grew up. We knew it was our job to care for our neighbor. You were your brother’s keeper. That idea went through everything in our lives — through our parents, the organizations they were a part of, the churches. On holidays my grandmother would have us kids perform, so we were always thinking: What are we going to do for Thanksgiving? What’s our performance going to be? What song are we going to sing? What poem are we going to read? Creativity was huge.

RS: If we can talk about this without sounding like a bunch of cranky old people, what do you think kids today are missing, in that stew you describe of creativity?

EH: Something I recall very fondly as a young person was being outside. There was a big field behind Tricia’s house, and there were apple trees back there, pear trees. It was a world where you could lose yourself. You could just pretend, because you had so much space and time to do it. Next door there was a huge schoolyard, and behind my house was a very spooky old barn that I used to make up stories about.

TEW: Oh, yeah.

EH: Just being outside and having that freedom without as much adult supervision as kids have today. Also, you couldn’t stay in the house on Saturday. You weren’t allowed. You had to go out. You had to breathe fresh air. You had to make up games. I think that part is missing.

TEW: Having that time, and playing without having a specific game. Freedom, exploration, time to be creative — all of that was there.

EH: Like you said, no television, no computers, no cellphones. Your mind had space. I heard this term the other day, “thinkering,” which is a combination of thinking and tinkering. Kids used to go out and grab some rocks and sticks and cardboard and “thinker” around and create something.

TEW: Also, I feel like there wasn’t as much fear. We certainly were told not to talk to strangers. But people in our neighborhood knew us, looked out for us — sometimes a little too much. I’d come back, and my mother would say, “I know you did this.” Ooh… But we felt freer in that way as well — we weren’t afraid of being out.

RS: I think children are raised with greater fear, partially because maybe it’s a scarier world; we’ve become more protective. But also, all of us, including me, have a much lower threshold for boredom. You’ve got that phone in your hand. You’re never left to your own devices, so to speak.

EH: Right.

TEW: Now you’re never alone. But we were alone sometimes — writing, painting, creating art.

EH: If a question comes up, instead of thinking about what the answer might be: “Just Google it.” Instant definition, instant explanation. And it’s so accessible, it’s probably minimizing our brain size a little bit.

RS: Don’t you hate it when you’re watching TV with people and you see an actor and think, I know that actor from what? And everyone’s trying to remember, but then someone has to whip out their damn phone and say, “I’ll look it up”?

TEW: Roger, that reminds me of an exercise I have my students do. They have to take themselves on an artist date twice a month — to go somewhere by themselves for an hour. Because of COVID, they can do it virtually, but I used to say, “You could go to a restaurant, a movie, a museum — just be by yourself, not on your phone, and see what that feels like.” So many times kids would be like, “But I’ve never gone to the movies by myself. I’ve never eaten by myself. What will I do for a whole hour?” They’re panicked about it.

EH: And I cherish that solitude.

TEW: Right. Then they like it, once they finally do it. They have to write a blog post afterward, and for the most part, they say, "I’m going to do this again."

RS: Ekua, you have a big exhibit right now at the Museum of Fine Arts. I’m curious if you’ve watched any children looking at your pictures.

EH: I have. I also asked the MFA to put out comment books, and there have been messages from children saying they felt reflected in the work. There are other paintings of children in the MFA, but this exhibition seems to strike people in the heart. So many people have written to me about seeing themselves, seeing their families, and feeling an appreciation for the stories I’m sharing. It’s been great watching kids with their parents. A child may be enamored of one particular piece — the parent might be ready to move on, but the child is not finished looking yet. It’s great to see that. We started planning this show before the pandemic, so we’d had a lot more hands-on, interactive elements planned. The exhibit has changed, but I feel like children are my number one audience. They were who I had in mind, and they are definitely coming through.

RS: You made me think of it, because for me a museum is a great place to be alone. Even if you’re with someone, you’re each experiencing the art you’re looking at independently.

TEW: And people go at different paces. I know I do.

RS: My husband has to read all the labels and captions, and I have no patience for that. I just go to the pictures I want to look at.

EH: But if you go to the MFA exhibit, I hope you will read the captions. I worked with teen curators — they were a wonderful group from Boston Public Schools. They each took a book, read it, thought about it, imagined and interpreted it, and it’s their words that form the panels for each of the books. They did a brilliant job. We’re always building bridges, but I think for people who are teachers, like Tricia and myself, we’re building those bridges to the younger generations. This was a great opportunity to do that.

RS: Your book is a great opportunity for building bridges, between children and the adults in their neighborhoods and lives, but also between children and their dreams, as we talked about before. The kid reading can realize that the dreams they have will also create a story.

EH: Everyone has one novel inside them. But it’s also important to me for young people to understand that their story is as important as any of the books they’re reading. And maybe they could share it, in whatever format — writing, illustrating, painting, singing — to take what’s inside of them and bring it out. It’s a form of love, to share your story.

TEW: And self-love. I was in a restaurant once, and this little girl, out of the blue, came up to me with a little stack of folded paper, and said, “Hi, my name is So-and-so, and I wrote this book. It’s twenty-five cents.” I was so astonished. I was like, “I will buy that right now. Can you autograph it for me?” And also I wondered: Who told you? How did you know that you could do this? I was so enthralled. I wanted to meet her mother.

EH: It does seem to me that this younger generation of artists — I’m over here at MassArt — I see that bold embrace of self-expression in a way that is different from my generation. There’s no hesitancy. There’s no overthinking. Instead of, I could never show at the MFA, they’re all thinking, When is my show at the MFA? I love it. I love that confidence. It’s generational confidence, it feels like. They talk about the baby boomers and the Gen-Xers. I feel like there’s an energy about this generation moving through time that’s very, very powerful and confident. I love seeing that.

RS: We’re going to need them to be that, won’t we?

EH: Absolutely.

TWE: True enough.

Sponsored by

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!