More Than a Footnote: Challenges for BIPOC Nonfiction Authors

For as long as I can remember, I have had three loves: jazz, poetry, and history. Those passions merged in my 2000 nonfiction title The Sound That Jazz Makes — a manuscript that was rejected more than a dozen times. The book’s first review was so negative that I cried. But then it won the Carter G. Woodson Book Award from National Council for the Social Studies — my first national honor. I had arrived!

For as long as I can remember, I have had three loves: jazz, poetry, and history. Those passions merged in my 2000 nonfiction title The Sound That Jazz Makes — a manuscript that was rejected more than a dozen times. The book’s first review was so negative that I cried. But then it won the Carter G. Woodson Book Award from National Council for the Social Studies — my first national honor. I had arrived!

For as long as I can remember, I have had three loves: jazz, poetry, and history. Those passions merged in my 2000 nonfiction title The Sound That Jazz Makes — a manuscript that was rejected more than a dozen times. The book’s first review was so negative that I cried. But then it won the Carter G. Woodson Book Award from National Council for the Social Studies — my first national honor. I had arrived!

Or so I thought. Subsequent pitches to editors and book reviews that I have received have confirmed for me how exclusive and subjective gatekeepers can be and how race figures into publishing outcomes.

This is evident even in rejection letters from publishers. My picture-book biography of African American stock car racing champion Wendell Scott, Racing Against the Odds, got multiple rejections. I was baffled until one editor replied — and I paraphrase — that NASCAR and African Americans are like oil and water; they don’t mix.

This is evident even in rejection letters from publishers. My picture-book biography of African American stock car racing champion Wendell Scott, Racing Against the Odds, got multiple rejections. I was baffled until one editor replied — and I paraphrase — that NASCAR and African Americans are like oil and water; they don’t mix.

When I pitched my manuscript of Before John Was a Jazz Giant: A Song of John Coltrane, I was excited by an editor’s initial interest. Later, I notified her that I had an offer and, as a courtesy, invited a counteroffer. “I’m not familiar with his music.” She declined.

When I pitched my manuscript of Before John Was a Jazz Giant: A Song of John Coltrane, I was excited by an editor’s initial interest. Later, I notified her that I had an offer and, as a courtesy, invited a counteroffer. “I’m not familiar with his music.” She declined.

The most stinging rejection of all, though, dismissed my proposed subject as “a footnote to history.” From then on, I vowed to rescue Black stories from the footnotes and the margins.

For me, this work is political. So, I educate editors and teachers about my subjects’ significance and assure adults that children are not too tender for tough topics.

My books about systemic racism provoke questions among readers. “Who made that stupid rule?” a boy asked after reading Freedom on the Menu: The Greensboro Sit-ins. Another student’s question referred to African Americans as “colored,” a term that fell out of favor in the 1960s. Such inquiry sparks much-needed cross-generational and cross-cultural conversations. When adults provide access to BIPOC books and foster an anti-racist climate, critical literacy can come naturally for children.

My books about systemic racism provoke questions among readers. “Who made that stupid rule?” a boy asked after reading Freedom on the Menu: The Greensboro Sit-ins. Another student’s question referred to African Americans as “colored,” a term that fell out of favor in the 1960s. Such inquiry sparks much-needed cross-generational and cross-cultural conversations. When adults provide access to BIPOC books and foster an anti-racist climate, critical literacy can come naturally for children.

So, imagine my disappointment when I discovered — after an unpaid, bookstore-arranged school visit before six hundred students — that the school’s library had just one of my fifty-some books. The librarian said that she couldn’t afford to buy everything. I hoped that she had at least bought books by my contemporaries or my predecessors.

The Black deans of nonfiction — James Haskins and Walter Dean Myers — have gone on. To continue their legacies, BIPOC creators like myself serve as mentors — through Kweli, We Need Diverse Books, the Highlights Foundation, or informally — to develop new BIPOC creators.

Yet, even as new BIPOC talent emerges and BIPOC subject matter gradually expands, white creators still get far more than their share of the market for nonfiction books about BIPOC. The business of equity remains unfinished and urgent.

The long-overdue #OwnVoices movement decries the historical omission, distortion, and appropriation of BIPOC narratives. But the movement has not deterred white creators from writing outside their culture, with permission or not.

My experiences are not anomalies, nor am I alone in this fight. I ally with other BIPOC nonfiction creators who center true stories that matter to our communities and to our country.

I asked some of my award-winning peers — a.k.a. my idols — to bear witness to the challenges, inequities, and opportunities that confront us individually and collectively. Their concerns ranged from the industry’s deficits in BIPOC representation and its discomfort with harsh historical truths to its dismal marketing expectations for BIPOC books. Here are some of their insights.

So much BIPOC history is little known, says Traci Sorell, author of the nonfiction picture book We Are Still Here!: Native American Truths Everyone Should Know. BIPOC narratives “are critical parts of our national identity,” she stresses, and “integral to our shared citizenry.”

So much BIPOC history is little known, says Traci Sorell, author of the nonfiction picture book We Are Still Here!: Native American Truths Everyone Should Know. BIPOC narratives “are critical parts of our national identity,” she stresses, and “integral to our shared citizenry.”

Poet Nikki Grimes, whose latest work of nonfiction is the picture-book biography Kamala Harris: Rooted in Justice, adds, “We have so many stories that are difficult, that reflect cruelty, discrimination, and injustice. But they are stories that need to be told.” Grimes wonders, though, “How can we get across the message that we are all of equal value if our books are only marketed to the people of our own group?”

Poet Nikki Grimes, whose latest work of nonfiction is the picture-book biography Kamala Harris: Rooted in Justice, adds, “We have so many stories that are difficult, that reflect cruelty, discrimination, and injustice. But they are stories that need to be told.” Grimes wonders, though, “How can we get across the message that we are all of equal value if our books are only marketed to the people of our own group?”

What’s needed, says Kelly Starling Lyons, whose most recent nonfiction title is the picture book Dream Builder: The Story of Architect Philip Freelon, is “a new understanding of history. African American history is American history. It’s not niche.”

What’s needed, says Kelly Starling Lyons, whose most recent nonfiction title is the picture book Dream Builder: The Story of Architect Philip Freelon, is “a new understanding of history. African American history is American history. It’s not niche.”

“Having others determine the marketability of my history is troubling and underscores the need for better representation in all areas of publishing,” says Lesa Cline-Ransome, author of the historical fiction picture book Overground Railroad, among many other titles.

“Having others determine the marketability of my history is troubling and underscores the need for better representation in all areas of publishing,” says Lesa Cline-Ransome, author of the historical fiction picture book Overground Railroad, among many other titles.

Underrepresentation puts an undue burden on BIPOC creators. “Having to offer up explanations…to those outside my culture,” says Cline-Ransome, “can feel like I am having to defend or justify my use of language or culture.”

Yet, as Sorell laments, “We continue to see white people getting published to share our stories, which read like they are written for other white people and not for young people from the communities represented.”

To make matters worse, white-authored BIPOC nonfiction can erode BIPOC creators’ opportunities. Don Tate, author-illustrator, most recently, of William Still and His Freedom Stories: The Father of the Underground Railroad, found this out the hard way. In a common publishing scenario, one of his books was almost killed after a similar book beat his to press. “It especially hurt,” he said, “that the author of the other book was white. In a perfect world, the race of an author would not be a consideration. But we don’t live in a perfect publishing world.”

To make matters worse, white-authored BIPOC nonfiction can erode BIPOC creators’ opportunities. Don Tate, author-illustrator, most recently, of William Still and His Freedom Stories: The Father of the Underground Railroad, found this out the hard way. In a common publishing scenario, one of his books was almost killed after a similar book beat his to press. “It especially hurt,” he said, “that the author of the other book was white. In a perfect world, the race of an author would not be a consideration. But we don’t live in a perfect publishing world.”

Far from it. The Census Bureau estimated that, in 2018, only about one half of the children in the U.S. and in America’s schools were white. Statistics show that the industry needs to catch up, says Sorell. “With publishing staff over eighty percent white, the industry is way behind where it must be to provide books that our young people need and want.”

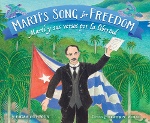

Student access to BIPOC books is crucial, says Emma Otheguy, author of the bilingual picture-book biography Martí’s Song for Freedom / Martí y sus versos por la libertad. “Most children have books only if their public institutions buy them,” she states. “When school districts subtract book purchasing from their budgets, BIPOC kids, authors, and books are the first to lose out.”

Student access to BIPOC books is crucial, says Emma Otheguy, author of the bilingual picture-book biography Martí’s Song for Freedom / Martí y sus versos por la libertad. “Most children have books only if their public institutions buy them,” she states. “When school districts subtract book purchasing from their budgets, BIPOC kids, authors, and books are the first to lose out.”

And no one wins.

From the March/April 2021 issue of The Horn Book Magazine.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!

Kamalani Hurley

Thank you for this post, Carole, for saying what needs to be said out loud. As a Native Hawaiian, I, too, have difficult stories of my indigenous community that need to be told. From Capt. Cook, through the annexation of our native government and statehood to today, our stories have been told by non-natives in their non-native point of view. I feel for those wonderful writers discussed in this post who continue to be marginalized, but I have hope that if we keep at it and not be disheartened, we will be heard. As our great king Kamehameha I once said to his young warriors at the start of a decisive battle, "I mua e na poki'i. A inu i ka wai 'awa'awa." We, too, must move forward and drink of the bitter waters; we must be strong and and not let anything discourage us.Posted : Oct 29, 2021 12:01

Penelope Librarian

Writing is one of the most difficult of professions for writers of all colors. Most writers of any color have day jobs they should not quit, even if after they have published for the first time or won a book award. I have been to enough librarian conferences and breakout sessions to hear that the experiences of Ms. Weatherford and the people she quotes are extremely common across all racial groups, including white writers. Published authors have trouble finding a home for their next kidit nonfiction book. Manuscripts that they love will languish. Books published do not find their audience well enough. Books are published only with a single publisher making an offer on it, and no counter offers. Books get preempted by other books on the same subject, while some hot or vogue subjects infuriatingly seem to have a million books about them because there seems to be an insatiable appetite on the subject matter, and why can't adults just steer kids to other topics? The existence of an inferior book from 10 years ago may deter a publisher from publishing a new book that the author is sure is better. Books are rejected for what seem like stupid rationales, and the author never knows if that is the true rationale or the editor is just blowing smoke at them. Libraries do not carry more than a few of an author's books, or maybe just the most famed one, even if the author has won awards. In this age of #ownvoices, publishers are pushing writers of color to write about subjects and people in their identity groups, so they can put an #ownvoices tag on their Twitter posts. Having other determine the marketability of history, subject matter, approach, or anything else is irritating, because the author is sure they knows better, though the author is in the business of writing and the publisher in the business of publishing and marketing. I have been to enough conferences and breakout sessions to have great respect for writers. They have a hard professional life.Posted : Apr 02, 2021 04:05

KT Horning

Thank you so much for this excellent article. I've read it three times now just to absorb it all. The reasons the author cites for rejections are heartbreaking, and speak to the importance of diversifying -- and supporting -- editorial and marketing staffs in the children's book industry. We see so many picture-book biographies every year about BlPOC figures that are written by white authors and illustrated by BIPOC artists. These get counted as #OwnVoices -- but are they really? Would BIPOC authors choose to write about the same subjects as white authors do? Please let's bring these stories from the footnotes and margins into the forefront.Posted : Mar 22, 2021 09:15

Christine Taylor-Butler

This is such an important topic. THANK YOU Carol for speaking our truths so eloquently, Seems to be we've all been shouting from the mountain top on this issue for decades. Over the last 20 years I've seen all of my Black editors leave their jobs at large publishers. Lack of support, lack of compensation, lack of credit for their substantial contributions. All of them have many BIPOC authors and illustrators on speed dial and most of us would work with them on projects in a heartbeat. But the default in the industry is white gatekeepers. None of the publishers has even considered that the fastest way to ramp up diverse initiatives is to hire back the experienced editorial directors who don't need a "translator" to understand the manuscripts and don't need to be taught a production schedule.The majority of children born in the US are now BIPOC. We will not see substantial change in this industry until those in the gatekeeping system (agents, editors, book buyers etc.) look like the children we write for. I'll add that diversity doesn't count if the publisher has to count the janitorial staff to claim they have critical mass.Maybe it's time we rallied behind publishing houses that are both BIPOC owned AND employ editorial directors and staff that look like us. Just Us Books, Reycraft Books, Move Books to name a few are small but have been willing to see our experiences as broader than the stereotypes that drive the industry. For now, the struggle is real.Posted : Mar 22, 2021 01:16

Joyce Uglow

Thank you for this much-needed, frank post.Posted : Mar 19, 2021 09:18