The CCBC's Diversity Statistics: New Categories, New Data

This is the fourth column in a series examining statistics gathered by the recently expanded database of the Cooperative Children’s Book Center (CCBC), a research library of the University of Wisconsin–Madison School of Education. Previous columns can be found at hbook.com/tag/ccbc.

This is the fourth column in a series examining statistics gathered by the recently expanded database of the Cooperative Children’s Book Center (CCBC), a research library of the University of Wisconsin–Madison School of Education. Previous columns can be found at hbook.com/tag/ccbc.

Since 1985, the CCBC has kept track of children’s books we receive by and about Africans and African Americans; in 1994 we also began counting books by and about Asians and Asian Americans, Latinxs, and Indigenous peoples. Beginning in 2018, thanks to a new database we created, the CCBC expanded the range of collected data to include representations of LGBTQIAP+ identities, disability, and religion. (Thanks to Uyenthi Tran Myhre, in 2019 we made Pacific Islander a separate category; it had until then been erroneously included in the Asian category. Additionally, Kay Tarapolsi’s feedback helped us to make decisions about the best way to track books by and about Arabs and Arab Americans, which we are beginning to do this year.) The COVID-19 pandemic may have set us back in our initial compilation of the CCBC statistics for 2019 books, but it also comes with a silver lining: extra time to dig into the numbers.

The new data is eye-opening and interesting in its own right, and it also provides a means for us to parse books in greater detail. Being able to come at the data from multiple angles makes it easier to identify books featuring characters with a greater variety of intersectional identities.

So what does the data tell us? (All analysis based on information in our database as of October 2020 for trade books from U.S. publishers.)

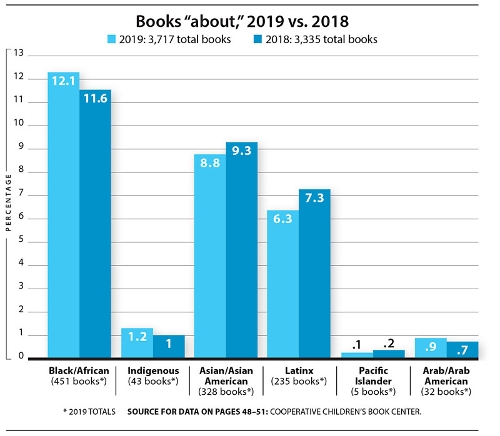

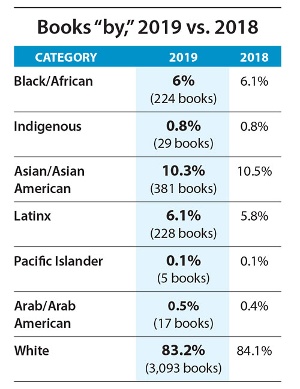

In 2019, we received 3,717 books from U.S. publishers. (In 2018 we received 3,335. Percentages from 2018 are included for comparison.)

Who and what were those 3,717 books about? For a book to be counted as “about” a specific category, a primary character, significant secondary character, subject, topic, and/or setting must fall under the specified category. For example, all of the following would be counted in the “Latinx” category: a novel with a Cuban American primary character (Sal & Gabi Break the Universe by Carlos Hernandez), a book whose characters come from various Central American countries (The Other Side: Stories of Central American Teen Refugees Who Dream of Crossing the Border by Juan Pablo Villalobos), and a nonfiction book about a paleontological dig in Argentina (Titanosaur: Discovering the World’s Largest Dinosaur by José Luis Carballido and Diego Pol, illustrated by Florencia Gigena). A single book may be counted in more than one category.

Who and what were those 3,717 books about? For a book to be counted as “about” a specific category, a primary character, significant secondary character, subject, topic, and/or setting must fall under the specified category. For example, all of the following would be counted in the “Latinx” category: a novel with a Cuban American primary character (Sal & Gabi Break the Universe by Carlos Hernandez), a book whose characters come from various Central American countries (The Other Side: Stories of Central American Teen Refugees Who Dream of Crossing the Border by Juan Pablo Villalobos), and a nonfiction book about a paleontological dig in Argentina (Titanosaur: Discovering the World’s Largest Dinosaur by José Luis Carballido and Diego Pol, illustrated by Florencia Gigena). A single book may be counted in more than one category.

Although these categories are broad, within each book’s database record we take note of additional ethnic and cultural details. For instance, a book about a Filipinx character (My Fate According to the Butterfly by Gail D. Villanueva) will be reflected in our Asian/Asian American category, and its internal record will note that the primary character is Filipinx, and that the story takes place in the Philippines, so the book will come up on a search for either of those terms. (Additionally, this book has an “LGBTQ Family” diversity subject, while its database record specifies that the primary character’s father has a male partner.)

Although these categories are broad, within each book’s database record we take note of additional ethnic and cultural details. For instance, a book about a Filipinx character (My Fate According to the Butterfly by Gail D. Villanueva) will be reflected in our Asian/Asian American category, and its internal record will note that the primary character is Filipinx, and that the story takes place in the Philippines, so the book will come up on a search for either of those terms. (Additionally, this book has an “LGBTQ Family” diversity subject, while its database record specifies that the primary character’s father has a male partner.)

Who wrote and illustrated those 3,717 books? The numbers below represent the number of books that were written and/or illustrated by at least one individual who identifies with the specified category. We use many methods to determine this information, including author/illustrator bios, publisher and author/illustrator websites and social media accounts, and interviews, and by asking the authors and illustrators themselves how they identify. We also occasionally consult content specialists, including people who are actively involved with the Coretta Scott King and Pura Belpré Awards. Again, a single book or creator may be counted in multiple categories.

***

A common question we get is whether our statistics can be used to determine how many books are #OwnVoices. The answer is no, these numbers alone cannot determine the extent of #OwnVoices. The “by” and “about” relationship is too variable to make direct correlations from these numbers to trends in #OwnVoices. The way individuals interpret #OwnVoices may vary, but the term is often tied to more culturally specific identity and experience than is captured in these broad categorizations.

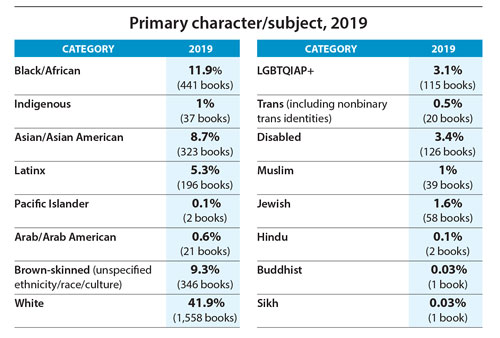

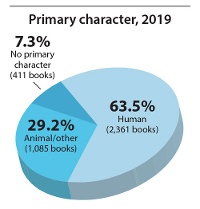

We now also track details about primary characters (or, in the case of nonfiction, subjects) specifically, including race and ethnicity, gender, disability, sexual orientation, and religion. Additionally, we now track whether characters are human, animal, or other (for example, a truck). A single book may fall into more than one category, and not all books have primary characters.

The numbers in the pie chart below represent the percentage and number of books with at least one primary character or primary subject of the specified identities.

***

The CCBC recently launched a redesigned website (ccbc.education.wisc.edu) with more advanced search capabilities. Visitors to the site are now able to curate lists of books based on the CCBC’s diversity statistics and the aforementioned categories. It is our hope that the additional categories and details in our statistics will make diverse books more accessible to those who are searching for them. A separate search on the website will be limited to titles we have recommended.

What does all of this mean? Our numbers continue to show what they have shown for the past thirty-five years: despite slow progress, the number of books with BIPOC creators and protagonists lags far behind the number of books with white main characters — or even those with animal or other main characters.

We are excited, though, about the many terrific books that are being written, books that offer deeply authentic depictions of characters and subjects across a vast array of identities. We are heartened to hear from researchers and educators who are now able to use the new CCBC website to access lists of books by and about people of multiple identities. And we are pleased to see more books that explore the intersectionality of identities.

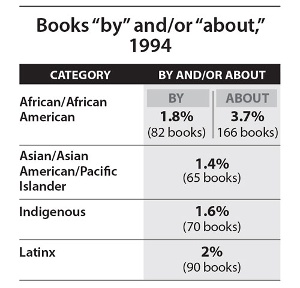

Finally, I’ll leave you with a look back at the statistics from 1994, when we first expanded our data to include four broad racial groups. (These numbers include a small number of books from non-U.S. publishers, and in 1994, we did not separate “by” numbers from “about” numbers, except in the case of books by and about Africans and African Americans.)

Diversity remains a central component of all the work done at the CCBC. In our everyday services to teachers, librarians, students, and others, we are reminded time and again that all young people benefit from books that authentically and positively represent the vast diversity of the world. As we compile our statistics, we hope to continue to see that diversity increasingly reflected in children’s and young adult literature.

From the January/February 2021 issue of The Horn Book Magazine.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!