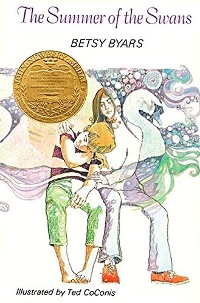

1971 Newbery Medal Acceptance by Betsy Byars

During the past few years I have on occasion found myself in front of a classroom or in a library trying to talk to children about writing books. I have never been a success at this. For one thing, I have learned that questions come in twos. If one child asks, "When did you start writing?" then the next question is going to be, "Wow, how old are you?"

During the past few years I have on occasion found myself in front of a classroom or in a library trying to talk to children about writing books. I have never been a success at this. For one thing, I have learned that questions come in twos. If one child asks, "When did you start writing?" then the next question is going to be, "Wow, how old are you?"

Or there will be no questions. Not one child can think of anything to ask, and I know that the important thing to children is not what I say, but what they say. The afternoon is a success if the child can walk out of the room saying to a friend, "Hey, did you hear what I asked?" Finally, on a slow afternoon, one child thinks of a question. "How long did it take you to write The Summer of the Swans?" Even before I give my answer another hand goes up. "How long did it take you to write The Midnight Fox?” Now a bolt of electricity goes through the room. Everyone has a question. The children are all but leaping into the air to be called on, because they are aware that there are twenty-eight children left and only six books. In moments like this I always feel that any writer worth his salt would at least have written enough books to go around.

Or there will be no questions. Not one child can think of anything to ask, and I know that the important thing to children is not what I say, but what they say. The afternoon is a success if the child can walk out of the room saying to a friend, "Hey, did you hear what I asked?" Finally, on a slow afternoon, one child thinks of a question. "How long did it take you to write The Summer of the Swans?" Even before I give my answer another hand goes up. "How long did it take you to write The Midnight Fox?” Now a bolt of electricity goes through the room. Everyone has a question. The children are all but leaping into the air to be called on, because they are aware that there are twenty-eight children left and only six books. In moments like this I always feel that any writer worth his salt would at least have written enough books to go around.

But, as of January, these difficulties are over. If the questions get personal or the afternoon is dull, I can say, "And now I'm going to tell you what it was like to win the Newbery Medal."

I get instant silence, rapt attention. I have already learned that no detail is too small or insignificant to be included. I can tell where I was standing when the phone began to ring that Tuesday morning. I can tell what I had on, what I thought when I picked up the phone. Even my first word in that fateful telephone call — "Hello" — seems strange and prophetic.

In fact, I have learned that there is no way to make a bad story of it. I admit to you, for example, that my part of the telephone conversation that morning was frankly disappointing for a person who had just won an award for words. I could not think of anything to say.

And I admit that when I hung up the phone that morning and turned around, absolutely bursting with this tremendous news, it would have been more dramatic if there had been someone there to share it with, other than two dogs and two cats. Still, you would be amazed at how pleased dogs and cats look when you turn to them and say, "Listen, I just won the Newbery Medal."

I would like to be able to tell you exactly how The Summer of the Swans was written, because I myself like nothing better than to hear writers tell how they happened to write their books. Often this is the best part. And long after I have forgotten details of character and plot, I can remember that a specific book was written in the shade of an olive tree by a wheat field in Umbria with a number-two pencil.

But I am like Jerome K. Jerome. He was asked how he wrote one of his books, and he said that actually he could not remember writing the book at all. He was not even sure he had written it. All he could remember was that he had felt very happy and pleased with himself that summer and that the view of London from his window at night had been beautiful.

I am like that. I know I wrote The Summer of the Swans, because two of my daughters claim it is the size of their feet that plays an important role in the story, and also I have a three-inch-high stack of rewrites that could not be explained in any other way. But all I really remember about that winter is that I felt enormously fine, that none of the children had the flu, and that the West Virginia hills had looked beautiful when they were covered with snow.

Since I cannot tell you exactly how The Summer of the Swans was written, I will tell you how I write in general, and perhaps you can imagine the rest.

I write in four stages. In the first stage I mainly sit around and stare at a spot on the wall or at my thumbnail. This is a difficult stage for a writer who has children. Anytime my children see me sitting there staring at my thumbnail, they come running over with skirts that need hemming and blouses that need ironing and baskets of dirty clothes.

I can protest for hours that I am working, that I am writing a book in my head, but they will not believe me. And the situation will end in bad feelings when one of the children says, "You just don't want to wash these clothes!" And, of course, there is no denying that.

The second stage is the best. At some point in this "head writing" I become gripped with enthusiasm. There is nothing like my enthusiasm when I first begin writing. People who have seen me in this stage would never ask, "How do you find time to write?" because it is obvious there is no time for anything else. I can hardly wait to get to the typewriter in the morning. I have even awakened in the middle of the night, glanced at my desk, and wondered if it would disturb my husband if I got up and typed quietly in the dark.

The third stage comes so gradually that I almost do not notice it, but soon the words which have been flying out of my typewriter in paragraphs, now start coming out in sentences. Then they start coming out in phrases, then one by one, and finally they do not come out at all.

I look on this as a desperate situation, requiring great personal discipline. This is what works for me. I say to myself, "All right, today you are either going to have to write two pages or you are going to have to defrost the refrigerator." Sometimes I do decide that the refrigerator is the lesser of the two evils. Sometimes I clean closets and wash cars, because writing at its worst is bad indeed. Sooner or later, however, I will find something that is worse. After all, there is always the attic.

The last stage is the longest and the most trying. It involves reading what I have written and trying to make something of it. I have never read a manuscript in this stage without becoming aware again of the enormity of the gap which exists between the brain and a sheet of paper. I just do not know how it is possible to have something in your mind which is so hilarious you are all but chuckling as you write, and then when you read it over, it is completely flat.

Or, there is a scene in your mind which is so sad, so touching, you can barely see the typewriter keys through your tears. And when you read it back, you find it is as touching and as moving as a recipe for corn bread.

I do not know how this happens, but I do feel that the gap be tween the brain and a sheet of paper is at least as formidable as the generation gap. And whenever I read statistics on the number of books published in a month or a year, I never think of all those books. I think, "That many authors conquered the gap this year!" And I am impressed.

In this last stage I always ask my children to read my manuscript, even though they are my severest critics. They are not in the least tactful about what they do not like, either. If they find, for example, their interest is lagging, they draw a small arrow in the margin of the manuscript, pointing downward. A small, downpointing arrow in the margin of a manuscript can be starkly eloquent. It can say more than a thousand words. In my most terrible and haunting' nightmares, I open a magazine or a newspaper to read a review of one of my books and find that the review consists of a great blank space, no words at all, and in the center of the space is a small arrow — pointing down. The possibility is enough to make one tremble.

Five years ago on the night before my son's eighth birthday he was enormously excited because he was getting a bicycle. Sleep was impossible and he kept coming in my room where I was working at my desk to tell me how much trouble he was having falling asleep.

Finally in desperation he said, "You know, maybe it would help me get to sleep if I read some of your failures."

I asked after a moment if there was any particular failure that would induce sleep better than the others, and he named one. I opened my failure drawer — I had never thought of it as being that before, but in an instant that was what it had become — and handed it to him. He read for about three minutes, yawned, went into his room and fell fast asleep. It was a humbling moment.

And I tell you about it because perhaps if you know I have failures that can anesthetize a child in three minutes, then you will know how very much I mean it when I say, "Thank you."

Betsy Byars is the winner of the 1971 Newbery Medal for The Summer of the Swans. From the August 1971 Horn Book Magazine.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!