2022 CSK Author Award Acceptance by Carole Boston Weatherford

I am grateful to the Coretta Scott King Book Awards Jury and for the support of Lerner Publishing Group and Carolrhoda Books, my editor Carol Hinz, art director Danielle Carnito, my agent Rubin Pfeffer, and my publicists Lindsay Matvick and Vanesse Lloyd-Sgambati. Most of all, I am blessed that I got this last chance to collaborate with Floyd Cooper.

I am grateful to the Coretta Scott King Book Awards Jury and for the support of Lerner Publishing Group and Carolrhoda Books, my editor Carol Hinz, art director Danielle Carnito, my agent Rubin Pfeffer, and my publicists Lindsay Matvick and Vanesse Lloyd-Sgambati. Most of all, I am blessed that I got this last chance to collaborate with Floyd Cooper.

I am also indebted to my mother, who wrote down my first poem after I recited it on the ride home from first grade. And to my father, a printing teacher who used my early poems as typesetting exercises for his students, allowing me to see my work in print — long before the dawn of the digital age. My parents’ affirmations helped me to endure both doubt and rejection as I grew into my gift.

As a child in the 1960s, I encountered few books with characters who looked like me. My elementary school teachers introduced me to the poetry of Langston Hughes, and my eighth-grade English teacher to other Harlem Renaissance writers. As a Black student at an exclusive private school, I was deeply moved by Countee Cullen’s poem “Incident,” in which a white boy calls a Black boy the n-word. But when I turned in my research paper about Cullen, my English teacher suggested that I had plagiarized. He was skeptical that a Black transfer student from public school could write an A paper. That slight left me determined to amplify missing voices that had been muted, marginalized, or muzzled.

Last but not least, I am grateful to my children, Caresse and Jeffery, whose arrival in the late 1980s introduced me to a new crop of children’s books. I read picture books by John Steptoe, Jerry Pinkney, Brian Pinkney, Nikki Grimes, Faith Ringgold, E. B. Lewis, Patricia McKissick, James Ransome, and Floyd Cooper. Their presence hinted that there might also be room for me in children’s publishing.

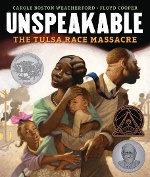

However, it was the late Tom Feelings, author and illustrator of The Middle Passage, who sowed the seed for Unspeakable when he shared with me his illustrations for a proposed and still-unpublished book about lynching. I later learned of an alleged lynching in my family’s lore. I decided to tackle the subject, but eventually shifted the focus from my own family’s loss to a greater tragedy: the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921.

However, it was the late Tom Feelings, author and illustrator of The Middle Passage, who sowed the seed for Unspeakable when he shared with me his illustrations for a proposed and still-unpublished book about lynching. I later learned of an alleged lynching in my family’s lore. I decided to tackle the subject, but eventually shifted the focus from my own family’s loss to a greater tragedy: the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921.

For more than seven decades, the Tulsa Race Massacre was all but erased from history. When the government finally mounted an investigation in 1997, most survivors of the massacre were long gone. Their voices were never heard, their stories never told, and their losses never measured. The Tulsa Race Massacre Commission confirmed what the Greenwood community had always known. A white mob, undeterred and in some cases deputized by local police, destroyed the Greenwood community, home to Black Wall Street. The violence left an estimated three hundred dead and nearly nine thousand homeless.

Unspeakable is a lamentation to that place. The book is a testament to the African Americans who built Black Wall Street and to the victims, survivors, and descendants of the Tulsa Race Massacre. Together, Floyd and I give voice to the victims and the survivors whose stories were never told and whose losses may never be fully measured.

Among those descendants was Floyd Cooper. I didn’t know that when I first messaged Floyd about a book idea. Our September 2018 exchange went like this:

Me: Hi Floyd. This just came to me: you and I should do a PB on Black Wall Street. I envision a book-length poem, perhaps starting with “Once upon a time.” I won’t be able to draft until January. What do you think?

Floyd: OMG. I must do this. I was born and raised in Tulsa, OK, near the intersection of Greenwood, Archer, and Pine streets.

Me: So, it’s a go. Once upon a time in Tulsa.

And so, Floyd and I set off. With research from the Tulsa Race Massacre Commission, the Greenwood Cultural Center, the Tulsa City-County Library, and Tulsa and Oklahoma historical societies, I took a forensic approach to storytelling. Readers are immersed in the reconstructed crime scene — the Greenwood of Black Wall Street’s heyday. There were barbershops, beauty salons, two newspapers, two movie theaters, over twenty churches, dozens of restaurants and grocery stores, fifteen Black doctors, six private planes, and the largest Black-owned hotel in the entire nation. Floyd’s cinematic art channels his grandfather’s memories and conveys this nostalgic panorama.

In 2018, the 2021 centennial of the massacre was not on my mind. Nor was any sense that this book would not only be Floyd’s crowning achievement but also among the last he would see published.

Carole Boston Weatherford and Floyd Cooper.

Photo courtesy of Carole Boston Weatherford.

Unspeakable focuses on a difficult subject and may seem an unlikely title to be celebrated. Yet, Unspeakable was the most honored book of the 2022 Youth Media Awards and has garnered more accolades than any other book in Lerner’s history.

But that is no guarantee that Unspeakable will be used in schools. Not in a climate where legislatures are demonizing critical race theory, banning anti-racist books, and deputizing citizens to police school curricula and to decide what other people’s children can read and learn.

A truth-teller like myself, Floyd would be appalled that books like Unspeakable are at the center of the culture wars over whose history gets told and who gets to tell it.

Viola Fletcher, the oldest living survivor of the massacre, was just seven years old in 1921. But the violence seared her memory. In May 2021, Mother Fletcher, at age 107, testified before Congress.

I will never forget the violence of the white mob when we left our home. I still see Black men being shot, Black bodies lying in the street. I still smell smoke and see fire. I still see Black businesses being burned. I still hear airplanes flying overhead. I hear the screams. I have lived through the Massacre every day. Our country may forget this history, but I cannot. I will not.

Nor can we let future generations forget. If children of the past could be victimized, then children today can at least learn to empathize.

By documenting history, Unspeakable links past racial violence to present-day attacks on Black lives. Hatred persists. But with each generation, hope is born anew, as is the yearning for justice.

During the fleeting formative years, we must pour every good thing that we can into our children to foster healing from historic trauma and to empower them to question injustice and to speak their own truth.

That is my life’s work. Sometime before conceiving Unspeakable, I sensed that I was building a historical cycle of narratives centering African American resistance, resilience, remembrance, and remarkability. I came to call my brand of nonfiction “Black Testament.” I carved out five categories: testaments to tradition; testaments in tribute; testaments of trials and trauma; testaments of triumph and transformation; and testaments to train up a child.

I hope this honor means that more children will read Unspeakable and choose hope over hate.

Since poetry brought me here, I’m going to close with a poem.

We’re Still Here

Drummers, dancers, masks and spears.

Musket fire! White men near.

Ancient kingdoms — Ndongo, Kongo —

Portugal pillaged long ago.

Bantu people, spoils of war,

Mined for rock salt and for tar.

Accepting Jesus Christ as Savior

Did not spare them from enslavers.

Traded, kidnapped, gone as ghosts,

Coffle trudging toward the coast.

Dungeons, castles, prisons, forts

Jailed the captives by the port.

The exit, “Door of No Return”;

For Africa, to always yearn.

Port of Luanda, 1619;

No words for the horrors seen.

Artists, healers, storytellers,

Genius nothing short of stellar

Herded out of barracoons,

Crammed below the deck like spoons.

In the belly of the ship,

Tribal chants still on their lips.

Middle Passage, waves of sorrow.

Hoping just to brave tomorrow.

Moans of misery, right and left,

Nightmares of disease and death.

Herded on deck twice a day.

The Motherland, so far away.

Beans and rice for nourishment.

Bid to dance to keep up strength.

The sea a grave, for one in five.

Only four in five survived.

British pirates, brutes so bold,

Stole the captives from the hold.

Pirates off of Mexico,

Cargo of “black gold” in tow.

Sixty Africans combined

On the Treasurer and White Lion.

Tempest raging, rations short,

Captain steers to Jamestown’s port.

Food and victuals, human cost:

“Twenty and odd,” most names lost.

A few days later, thirty more

Arrived upon the colony’s door.

Indentured, charter generation

Bartered in an unborn nation.

Gradually the Africans saw

Enslavement harden into law.

First to fall in the Revolution,

Short-changed by the Constitution,

Counted as three-fifths a man,

We bore the burden, wore the brand.

Seven hundred thousand enslaved

In a land our hands had made.

We raised tobacco, rice, and grain,

Indigo, cotton, sugar cane.

We cleared the forests for canals,

Built the White House and capitols.

Woodwork, patchwork, iron gates.

What crafts didn’t we create?

Importation, finally banned,

But not the right to own a man.

Driven, whipped, chained and penned;

Treated more like beasts than men.

Revolts, uprisings, mutineers.

Armed with truth, we persevered.

Slavery — borne of planters’ greed —

Spreading like a stubborn weed.

Forced labor filled the planters’ tills;

Fueled New England textile mills.

Some shed the shackles, disappeared,

Fled to freedom, clear of here.

Worth two thousand bucks a head,

Some in bondage, masters bred.

The auction block, our dire fear.

Families torn, but we’re still here.

Free blacks trod an uphill road

Blocked by ever-changing codes.

When the Civil War broke out,

Three million enslaved, most in the South.

Bloodshed — more than hearts could bear.

Republic ripped by slavery’s snare.

Emancipation Proclamation.

Hallelujah! Liberation!

Two hundred thousand, some once chattel

Joined the fight, the bloody battle.

Lee surrendered. War was won.

Finally, Jubilee had come.

But freedom was not full or fast;

A people, pegged as second class.

Strivings, struggles, streams of tears.

We may weary, but we’re still here.

Sharecroppers never getting ahead.

Countless lynched or left for dead.

Discrimination ruled the day,

Showed no signs of giving way.

Sick and tired of being oppressed,

Six million moved up North, out West.

But fortune wasn’t waiting there.

Just more closed doors and no fair share.

American dreams, African heart;

We drew upon our gifts and smarts.

Though mourning kin who died in chains,

Our push toward progress never wanes.

Come marches, sit-ins, freedom rides.

Conscience, justice on our side.

Great feats, proud firsts, new frontiers,

Barrier-breaking pioneers.

Ancestral spirits are with us still.

They are breath as we scale this hill.

A past so rich against great odds.

Whose hand uplifts? Most surely God’s.

Our legacy, four-hundred-plus years.

Forty million strong and we’re still here.

Yes! We’re. Still. Here.

* * *

Today, I stand on the ancestors’ shoulders. I did not dream that I would have staying power in this industry, let alone recognition. I did not dream that I would work with so many gifted illustrators, let alone my own son, Jeffery Boston Weatherford. I am blessed beyond my dreams. And I am still here.

Carole Boston Weatherford is the winner of the 2022 Coretta Scott King Author Award for Unspeakable: The Tulsa Race Massacre, illustrated by Floyd Cooper and published by Carolrhoda, an imprint of Lerner. Her acceptance speech was delivered at the annual conference of the American Library Association in Washington, DC, on June 26, 2022. From the July/August 2022 issue of The Horn Book Magazine: Special Issue: ALA Awards. For more speeches, profiles, and articles, click the tag ALA 2022.

Single copies of this special issue are available for $15.00 including postage and may be ordered from:

Single copies of this special issue are available for $15.00 including postage and may be ordered from:

Kristy South

Administrative Coordinator, The Horn Book

Phone 888-282-5852 | Fax 614-733-7269

ksouth@juniorlibraryguild.com

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!