Jesús Trejo and Eliza Kinkz Talk with Roger

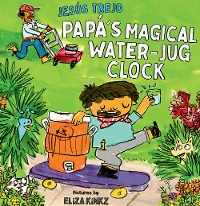

In Papá’s Magical Water-Jug Clock, standup comedian–turned–picture book author Jesús Trejo and animator-turned-illustrator Eliza Kinkz bring a funny but heartfelt story from Jesús’s childhood to vibrant life.

Talks with Roger is a sponsored supplement to our free monthly e-newsletter, Notes from the Horn Book. To receive Notes, sign up here.

Sponsored by

Astra Books for Young Readers

In Papá’s Magical Water-Jug Clock, standup comedian–turned–picture book author Jesús Trejo and animator-turned-illustrator Eliza Kinkz bring a funny but heartfelt story from Jesús’s childhood to vibrant life.

Roger Sutton: Jesús, how did you go from standup comedy to writing a picture book?

Jesús Trejo: Because my parents both worked long hours and couldn’t afford childcare, I basically grew up in a library. I want to go on record saying this: Librarians were my first influences in life. I became enamored with storytelling and writing, and I got into standup comedy. I’ve been doing it now for going on seventeen years.

Jesús Trejo: Because my parents both worked long hours and couldn’t afford childcare, I basically grew up in a library. I want to go on record saying this: Librarians were my first influences in life. I became enamored with storytelling and writing, and I got into standup comedy. I’ve been doing it now for going on seventeen years.

Author photo credit: Frankie Leal.

RS: I would imagine that the demands of a standup routine (I’ve watched a bunch of yours on YouTube; you’re very funny) and a picture book are different.

JT: Believe it or not, there are a lot of similarities. I’ve spent most of my adult life trying to write jokes: setup and punch, a story. As a standup comic, you strive to get the ultimate five-minute set, something you would see on The Tonight Show or The Late Late Show. For comedians, that’s the ultimate showcase where the world gets to see us in a five-minute set. I think a children’s book is a lot like that. There’s a lot packed into just a few pages. You need to tell a story. You need some humor. You need to hold people’s attention. Even though it’s a short period of time, you can lose people’s attention quite easily. I felt like the transition was very similar. They have a lot in common, and I felt like it was natural, going from one to the other.

RS: Is it based on a story from your own childhood?

JT: Yeah. My father was a landscape gardener, and I grew up (in Long Beach, California) working with him, weekends and that kind of thing. We had a running inside joke: my dad convinced me that he was able to tell time based on how much water was in this big dusty water jug. I would think, How the heck does he do that? He would go on to say, “You know how I know it’s time to go home? When the water’s gone.” And I’d think, Whoa. I took it at face value. I wanted to go home early one day, and I started throwing water left and right, giving it to the cats and washing the truck. It’s 10:30 a.m. The day is basically just getting started. And I go to my dad and say, “Dad, it’s time to go home. The water’s gone.” And he says, “No, we’ve still got a bunch more houses, buddy.” It’s based on this very fond memory of my upbringing, working with my father.

RS: It seems that your attitude toward your characters has to be different. When I listen to your standup, and you tell stories about your parents and about yourself as a child, you’re kind of poking fun at everybody. It’s affectionate fun, but you’re making jokes about your family to a roomful of adults. If you told this story as a standup routine, how would it be different?

JT: I think you’re able to tell the same story in different ways. You understand your audience. For me, if I was to present the exact same premise and story to a comedy club, it requires a lot less setting up. Certain variables are already defined, so I can go into a story and I can tell you the second part of the story, which is that my dad was really upset. But in a children’s book, you explore the father-son dynamic: he wasn’t going to fire me. I’m basically curating the experience for the audience. I pride myself on being able to tell that story effectively knowing who my audience is.

RS: But you’re also telling it from a different point of view. If you were telling it in a routine, it would be an adult Jesús telling a story about his childhood. But in this picture book, we’re really inside the head of young Jesús.

JT: Yeah, it’s a mischievous little kid who understands things at face value. I think Eliza and I were able to tell that story. Her ability to bring these words to life is nothing like I’ve ever seen before. I’ve been influenced by comedians like Buster Keaton, the Three Stooges, Laurel and Hardy. The visual punchlines that she brings to the page bring out a sensibility that I can’t express because I’m not on stage, acting things out. I’m limited in my channels of communication, and Eliza came in there and gave me all these other tentacles to work with.

RS: For both of you, what’s it like to have to share the stage, as it were?

Eliza Kinkz: It’s been great. I was a little worried because, coming from animation, I’ve had some experience with celebrities in the entertainment industry. I was a little scared when I first met Jesús. We met in person in LA, a month or two back, and I said, “Oh, I don’t want to take up too much of your time.” And he said, “No, let’s hang out all day!” We hung out in Long Beach and walked around, went in different shops, and got to really know each other.

RS: What’s it like to meet somebody with whom you’ve already had this intense artistic connection? You said you didn’t meet until after the book was done.

JT: To meet after the fact — I don’t know how to explain it other than you’re meeting up with a buddy where you pick up where you left off. We’re already on the same wavelength. We both think in cartoons; we’re both silly people.

EK: It was so nice to get to know each other. Jesús was so friendly and laid-back. I felt like I was just hanging out with one of my cousins for the day. When I was working on the illustrations, I talked to Jesús, trying to mine ideas for the backgrounds. Our publisher was awesome about that. I’d ask questions such as, “Did you collect stuff as a kid? What was your apartment laid out like?” I feel like it gives a depth to the drawings when it’s a reflection, especially with a personal story like this. If it was a dragon story, I wouldn’t be as worried but it was his home life. I think it adds another layer to the illustrations, and a layer of fun. In the last illustration, young Jesús is drawing on a piece of wood. Early on before I’d even done sketches, we were talking about how his dad always had a piece of wood on the van to cover a missing window. I had asked, “What was the van like? Was there anything wrong with it?” When Jesús told me about the wood, I thought it was such a good kid thing. A kid would think, Oh, awesome, my window’s knocked out and has a piece of wood on it; now I can draw on it.

JT: It was so cool to share those actual photographs. Initially we shared them through the publisher, sending photos of my upbringing, what I looked like. I don’t show those pictures to a lot of people. I felt comfortable enough to show them to Eliza and see them come to life. The coolest thing ever was seeing my dad look at the book cover; he said, “Oh, man, that’s me.” I see him in real time do the double-take. “Wait a minute, that’s not — oh, man. I remember that hat.” That speaks volumes to Eliza’s work, and the dynamic we brought to this book. To go back to your question about how it’s different in a book and on stage — on stage, I get to do act-outs, and I get to do faces. I can’t do that here. But Eliza was just like, Kobe and Shaq, boom, alley-oop, right in there.

Dummy drawings

Work-in-progress

RS: I love the tone of this book. It has humor, but it’s gentle. When I think of some…unfortunate picture books written by standup comedians, they’re punch line, punch line, punch line. This isn’t that kind of book. Also, it doesn’t feel nostalgic, which is another trap for celebrity picture books.

JT: It’s interesting that you say that, because when I decided to be a standup comic, I had to learn it was not just about making jokes. Everything I’ve done in my adult life has pointed to writing a joke. I love to do it, but what it really comes down to is good writing. You work and work this premise to be able to tell a story. You have to make it right, second by second. In books, you have to make it right so people — the reader, the kid, the parent — are excited to turn the page and keep the story going. They’re short, but so much can happen in the book. A good picture book is tight and packed with a lot of stuff, just like a set. It’s been awesome to see how my writing style and my point of view fit into this beautiful world of kids’ books.

RS: Eliza, how did you fit yourself into this? What did you think when you got the manuscript to consider?

EK: When I got the manuscript, I read it and really liked it. It has so much heart. With Jesús’ writing, like you were saying, it’s not about the punch line, looking for easy jokes. It was very sweet. And then I watched this documentary that he has out about taking care of his parents, and I was really touched by that.

JT: One of the things I was really excited about is having this book released in Spanish as well. My partner, Adria Marquez, was in charge of the book’s translation, and it was more than just translating the story. She acted as a cultural consultant, if you will. We had an in-depth conversation about my experiences growing up, as the son of immigrants in California, and how that shaped our language. We wanted the Spanish version of this book to be authentic to my culture and celebrate the experiences of immigrants coming to this country. It’s funny: my parents’ native language is Spanish, but they come from a rural part of Mexico. My dad is from Sinaloa, my mom’s from Jalisco, and neither had formal education. We wanted the book to shine a light on how that plays a part in how we spoke, how we communicated, how we expressed ourselves. From little Jesús’ point of view to the gardening tools my dad used. We used those words. My dad called the weed wacker a weedio, which doesn’t even make sense in Spanish. I was super-pleased to have Adria be a part of the translation.

RS: In the English edition, which is what I have, we do have occasional Spanish words that we can understand from context if we don’t know them. Is the same thing going on in the Spanish edition? Do you have English in that?

JT: No, it’s all Spanish. But like the word we use for weed wacker, weedio, that’s not even Spanish, so there’s bringing a little bit of the American experience the other way. Because the story’s native home is in Spanish, there’s less that needs to be set up or translated.

RS: What did you speak at home with your parents?

JT: All Spanish. My first language is Spanish. I didn’t have command of the English language till roughly fifth grade.

RS: You certainly seem to have managed well with it.

JT: Thank you. There was a point in time where my dad said, “You can’t speak Spanish or English.” It was that in-between, you forget a little bit of this, you gain this, and vice versa.

RS: Eliza, what’s your background?

EK: My dad is Mexican, and my mom is white. We’ve been in Texas forever. My dad was scared to speak Spanish to us; the Spanish down here is more of a Spanglish because they’ve been here for so long. People from Mexico would tell him, “Oh, you’re speaking Spanish so wrong.” And then Texans would say, “Don’t speak Spanish; speak English.” So he was scared to teach us anything. It is funny: whenever there was something grownups didn’t want the kids to hear about, everybody would start speaking Spanish. I would really know it if I brought a boyfriend home that they didn’t like.

RS: Did you feel that as a Tejana, you had a particular connection to Jesús’ story, or is it really different?

EK: I felt a big connection. When I saw the documentary, I thought, This is just like my tías and my tíos, or my grandparents in San Antonio. It’s so much of the same culture and challenges. Trying to hold onto your culture, but you’re in America, so you’re dealing with being American. Then you’re dealing with you don’t want your kids to lose their culture, but you want them to have a good place in America. I felt all that in Jesús’ story.

RS: As a reader, though, I felt like I understood too. It was clear I was in a world that wasn’t mine, but I could recognize those people. I could put myself in that little boy’s shoes, misunderstanding something, or understanding it the way he wanted to understand. I can’t say it felt really embedded in the Latino experience, because obviously that’s not my experience, but I felt like I was in a culturally authentic moment.

RS: As a reader, though, I felt like I understood too. It was clear I was in a world that wasn’t mine, but I could recognize those people. I could put myself in that little boy’s shoes, misunderstanding something, or understanding it the way he wanted to understand. I can’t say it felt really embedded in the Latino experience, because obviously that’s not my experience, but I felt like I was in a culturally authentic moment.

EK: That makes me so happy to hear.

JT: When I look back on my childhood, I realize that there were no books that had kids who looked like me, no books where the parents had the jobs that my parents had, who talked the way that my parents did. I decided to write one that did include those things, and to hear you say those things really warms my heart, because it sounds like you’re resonating with a story where you may not have skin in the game, but you felt it. That’s really cool, Roger.

RS: I think readers will feel it, because that little boy is so real, and so immediate. That’s to both of your credit, to convey that world. We’re with him in that story. That’s the first thing a picture book artist and author need to do.

JT: When you watch a TV show, when you watch a movie, when you read a kids’ book, you hope that people are able to see all the hard work, the love, the humor, the value. That’s across the board, regardless of background.

RS: And by being most authentically yourself, in my opinion, that’s how you reach people. Don’t try to be something that you’re not. Don’t try to convey an experience you don’t understand. But you reached back into your own story, and by sticking with that, I saw a real person. I saw a real little kid. I’m not even saying that’s because it’s a true story. That’s irrelevant. But the fact that the two of you created this real world of a boy, a father, and a day spent working together. Did you get paid, Jesús, when you were little?

JT: Yeah, at some point I started figuring out, Oh, wait, there’s pay involved. I got thirty dollars for a whole day’s work. And the deal was we would go to this taco shop by our place on Magnolia Avenue where I’d get as many al pastor tacos as I could eat. I was always up for the challenge. It was great. I probably ate more in tacos than I got paid in cash.

RS: How old were you when you started working with your dad?

JT: It was ever since I can remember. As a little kid, my dad would bring me along and tell me to hang out here, come watch me do this, rake leaves…I’m just raking the same leaves over and over. Later I had more responsibilities. So it’s hard to say a point in time when I started, because I was always around him.

RS: Sometimes when we ask a kid to help us, it’s just to make the kid feel good, make them feel included. But the boy in the book had real responsibilities. When his dad was trimming the top of the tree, the boy would be trimming the bottom of the tree. It wasn’t a game.

JT: It speaks to the Mexican American experience. I did this documentary years ago about caregiving and doing standup, and one of the things we explored was that I was a caregiver long before I knew I was a caregiver. Just being a Mexican American in this country, my parents had very little to no schooling, so from a very young age I was translating things that maybe I shouldn’t have been a part of like going to doctor visits with my mom and having to translate to the best of my fifth-grade ability. I shouldn’t know the difference between a W-2 and a 1099 at age eleven, but I did. I was filling out those things. I was filling out medical insurance forms for my mom, and for myself. The tree-trimming scene was a fun way to show that sometimes dads do the stuff way up here, going to work, but in the same tree also lies the paperwork and the Mexican American experience, my end of the deal. There was always a big sense of responsibility. As a kid, we want to help, right? When you’re a kid, you want to help the family.

RS: You both do this deceptively casual thing, Jesús, you with words, and Eliza, you with the pictures. I wouldn’t call them childlike exactly, but there’s something cartoonish in a good way about them. Just like the way Jesús tells us the story in a very natural way, it seems to flow very naturally from moment to moment.

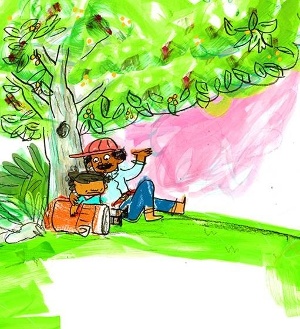

EK: It took me a long time to get the line quality where it looks like it just happened. The way I paint is I draw out an illustration ahead of time, figure out how and where I want the drawing to be. And then I paint separately. I think it’s something left over from working in animation. I lay the drawing on a light table, then I put my watercolor piece of paper on top, and then I’ll mark where stuff is supposed to be, but it’s not exact at all. I will do the whole picture book, every part of it, all at once. I’ll have all the drawings laid out along all the edges of my studio. If a certain type of green is called for here, I’ll mix that green, and I’ll go through (and it will be very fast, because I’m trying to make this green last before it runs out), and I’ll just keep going back and going around and around and around until it’s finally all done. I should say that I plan it ahead. I figure out what colors are going to go where. I have a little map on my computer, but it’s still not exact. At least for me, because that also leaves something, the sort of chaos of it for a second. There’s a second in there where I’m like, What’s going on? What am I doing? But then I get to that hill, and it’s like a slide all the way down. And then when I assemble the painting from the drawing, I put them together in the computer, it’s always this moment of, What’s it going to look like? And sometimes I’m like, Oh my god, I didn’t even know that was going to happen, and I get so excited. There’s a moment I love in the book where Jesús is hugging his mom, and it’s like his mom is absorbing his hug, and she’s absorbing some of him.

RS: How it should be.

EK: Yeah, it’s what a hug should be. It’s a happy accident that then isn’t an accident. So I question, is it an accident?

Finished drawing

Watercolor sketch overlay

Painting

Digitally combined line drawing and painting

Color-corrected image

RS: There’s a lot of planning that goes into it for both of you. Jesús, when I was watching your routines on YouTube, you would sort of rattle along, talking to the audience very casually, and then suddenly, a joke would appear that clearly had been planned from the very beginning of that section of your monologue, but you had to make it look like it had just occurred to you. I think that you both accomplish that in this book, where it looks easy, but there’s a ton of work that goes into it.

JT: I am so taken aback by your kind words. I think Eliza and I want to give you one of those soaking-in hugs, a group hug. You’re picking up on all the things that Eliza and I have worked very hard to protect our art and have this perfect match happen, this perfect creative match. We thank our editor Maria Russo and the team at ASTRA for bringing us together!

Sponsored by

Astra Books for Young Readers

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!