Tae Keller Talks with Roger

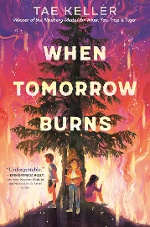

In Newbery Medalist Tae Keller's When Tomorrow Burns, middle schoolers Nomi, Arthur, and Vi — once inseparable childhood friends — need to come back together to face an ecological threat.

Talks with Roger is a sponsored supplement to our free monthly e-newsletter, Notes from the Horn Book. To receive Notes, sign up here.

Sponsored by

In Newbery Medalist Tae Keller's When Tomorrow Burns, middle schoolers Nomi, Arthur, and Vi — once inseparable childhood friends — need to come back together to face an ecological threat.

Roger Sutton: You have written a picture book, but your zone is really middle grade, middle school. What did you read in middle school?

Tae Keller: I really liked fantasy. I liked to read things that had at least a hint of magic. I was a kid who tried to believe in magic for a lot longer than was normal for my peer group. But I just wanted to believe that there was magic in the world. So I loved fantasy. But I also loved a lot of other writers that are still writing books today. I read Speak in middle school.

Tae Keller: I really liked fantasy. I liked to read things that had at least a hint of magic. I was a kid who tried to believe in magic for a lot longer than was normal for my peer group. But I just wanted to believe that there was magic in the world. So I loved fantasy. But I also loved a lot of other writers that are still writing books today. I read Speak in middle school.

RS: I feel so old.

TK: [laughs] Yeah, but it was pretty groundbreaking for me. And it shifted my idea of what adults could say to kids. I had felt before that, maybe in some way, adults were shielding kids from reality, and reading that book just made me think, Oh. Someone's just saying the truth. So that really impacted me. And I loved Lisa Yee’s Millicent Min, Girl Genius. It’s just so cool to be writing alongside those writers now.

RS: I don’t think I could be a middle-schooler today. It looks absolutely terrifying.

TK: I felt, when I was a middle-schooler, like I couldn’t be a middle-schooler! And now it just feels increasingly harder. It’s hard to visit schools and talk to kids and want to be honest with them and want to not lie to them about the world or dismiss their anxieties about the future but also provide comfort. I’ve found that to be an increasingly difficult balance in the world we live in.

RS: And do you think it’s actually different now, or does it look different to us because we’re adults?

TK: I think about this question a lot.

RS: It looks terrible. Like the scene in the book when Vi is texting with that guy from school and he’s like, “Send me a picture.” I’m like, “Oh, no.” That couldn’t have happened when I was in middle school.

TK: When I was in middle school, my class got laptops. We were the tester class of having the internet at our fingertips. And that really impacted what we were seeing in the world, because we could access anything online, but also how we interacted with one another. But I didn't have a smartphone until college. So at least I was sheltered from that. I do feel, increasingly, like the world is on fire.

RS: Fucking terrifying.

TK: And that we adults are behind on the technological curve, so we don’t know enough about how to teach and protect them. I do think it’s harder to be a kid now.

RS: And what do you think reading can do for that?

TK: I think reading is a safe place to explore scary things. For instance, the book has the element of this (relatively intimate) photo, like you were saying. I wanted to include that situation because it is something that happens. But I feel like in books you can include things that feel scary, that we feel kids shouldn’t have to experience, but in a way that’s safe and can offer some guidance and answer some questions. Rather than, if they have questions and then they Google something and there’s a million different results, and no filter of any adult to help them or guide them.

RS: Right. And frequently contradictory information.

TK: Yes. So yeah, I think books can be a safe space. And even now, as an adult, I feel like when I am thinking about big scary ideas, the space of a book is inherently a thoughtful and reflective place to be in. And you can also read it at your own pace. I think that is really important in a world that feels so inundated with information all of the time, to be able to pick up a book and if something gets too intense for a kid, they can put it down. They can take a break. They can leave it if it’s not right for them. Or they can come back to it when they feel ready.

RS: How do you decide how many characters you're going to focus on? Is three a good number?

TK: Oh, that's a good question. I hadn't done three characters before. I started with the idea of, “How do we live in a world on fire?” I wanted to explore the literal climate, the wildfires, but I also wanted to explore metaphorical fires. And I had these three distinct fires that I wanted to explore. Sometimes I have an idea for a character or their arc and I start writing them and I can't quite find their voice. But for all three of these characters, pretty early on in the drafting process they felt real to me. And that was a sign for me to keep going. And to find the way their separate fires ultimately intersected with one another.

RS: And with the world, right? The threat of fire hangs over most of the book.

TK: Yeah. When I'm thinking of how to build a book, I feel like I'm going through life collecting different ideas that spark something or excite me. And I’ve had the idea of a wildfire for a while. In 2019, I was in Malaysia for my honeymoon and it was during a really bad wildfire season for them. It was the first time I was in a place where there was such bad smoke. And I was just so struck by that. Before, when I was thinking about the climate crisis, it felt real but also removed, hypothetical in some way. Malaysia was the first time I had to really confront it. I remember looking out the window and feeling like it looked like the world just...ends. You know, you can see a certain amount into the distance and then because of the smoke it's just gray, and it's like the world stops. That has stayed with me for years. And it was the kind of recurring image I knew I wanted to put in a book at some point. I had been thinking of this plot for Vi and had been wanting to explore sexism in middle school. But it wasn’t until I moved to Seattle in 2021 and experienced a wildfire season here that these different elements all of a sudden came together. And it felt like, Okay, it’s time to write this book.

RS: How do you know — or maybe the answer is you don’t know — but how do you know if you’re going down a blind alley with a book? I mean, that would be so hard, to do all this writing and thinking and creating and then realize, Oh, no…

TK: Yes, Roger. I do a lot of drafts. For all of my middle-grade books I’ve written about twenty revisions, so there are a lot of blind alleys. I usually draft quickly because I do so many; I’ve learned not to be precious about it. And I tell myself that if I’ve gone down a path that doesn’t work, it’s fine because that’s just part of the process. It’s learning what does work. And I don’t think I would find the right path if I didn’t explore paths that didn’t quite work out.

RS: And did you have any major roadblocks in this one?

TK: Oh, yeah. I have major roadblocks in all of them. For a long time I couldn't figure out the unifying thread of the book. There are these three kids and then there are these interludes that are told from the point of view of the trees in the forest. And that took me a long time to figure out. I knew that I wanted to include history, pieces of Seattle’s history, because the more I learned about the place that I lived and the more I was panicking about the state of the world, the more I found comfort in learning about history and the people who came before me and the people who have been fighting the good fight and working to make a better future and to protect future generations. I felt like that was such a crucial part of the story I was telling about this question of how we live in a world on fire. Part of the answer is knowing that history is long and that there are people who’ve come before us that have paved a path for us and that we can be part of walking that path too. I couldn’t figure out how to include all that, and that was a big struggle for a long time. It felt like there were these gaps in the book that I didn’t know how to fill. And then, with the wildfire element, I started learning so much about trees and nature as part of my research. And at a certain point, when I was learning about the ways that the forest is connected, with the root system and the way that the forest canopy is...

RS: ...basically one big tree, right?

TK: Yeah, yeah! I felt like, “Oh, this kind of connects to how I’ve been feeling about history and humans and how we’re all connected.” I felt like, “Thank you forest, for teaching me this.” And then it was this epiphany, like the forest could literally be speaking in the book.

RS: If I can talk to it, maybe it can talk to us.

TK: Yes.

RS: So, you moved to Seattle in 2021 — you haven't lived there all that long.

RS: So, you moved to Seattle in 2021 — you haven't lived there all that long.

TK: No, I've had family in the city my whole life and I've always loved it. I had this idea of, “One day I want to live in Seattle.” But no, I haven’t been here that long, and I think writing this book was my way of learning about the city and making it home.

RS: We’ve talked a lot in recent decades about writing your own story and telling your own story and where you come from. But there is also something to be said for entering a new space because you want to learn about it, as you’re saying. And you have that excitement of the outsider coming in and seeing something new. I guess the danger is not to assume you know more than you do.

TK: Yes.

RS: But I was fascinated to learn so much about Seattle. And that underground tour, that’s a real thing?

TK: Yeah, that's something I had done multiple times as a kid when I visited my family. It’s really cool. There’s an infinite amount that you can learn about the history of a place. And I wanted these tree-history chapters to feel like snapshots almost, pieces of a whole to give the sense that actually the whole is infinitely big.

RS: Well, it gives your characters grounding. The message they read on the billboard —

TK: “Ground from the earth.”

RS: Your characters are “ground from the earth.” This would not be the same story had you set it in your native Hawaii or my Boston.

TK: Yeah, and I think that is what’s so beautiful. Over the course of my writing career, I’ve definitely learned the importance of setting. When I was starting out, I felt like the setting was just backdrop. But as I’ve learned a lot as a person and also as a writer, I recognize how much the place we are in influences who we are. I think that is so important to remember and to understand ourselves as the result of the people and the history around us, and also to recognize the importance of learning and engaging with that history.

RS: Because it helps create you. I mean, although you're not native to Seattle, it is now doing its bit to create you, Tae, as you go on.

TK: Yeah, yeah. I think being intentional about learning history has informed the way that I see the world and the way that I interact with the world.

RS: Well, there’s where we’re from, but there’s also where we are. And those two things are always intersecting.

TK: And then with the reader, whenever they’re reading it, it’s like a book is speaking to the future in that way. And I think that’s why different generations will interpret art completely differently, because it’s all of that context the author had, but then also the context of what the world looks like when the book is read.

RS: Right. And some books will continue. Read and loved by generations and generations of people, which is really neat. And some books, however beautifully and provocatively they speak to the moment, once that moment is gone, people are like, “What? Why did people read this book?”

TK: Or the reverse. A book might not have been appreciated in its time, and then it’s found later.

RS: Or a book that makes its mark when it’s published disappears quickly and then is rediscovered a century later. You can’t know, right? I think that’s part of the fun.

TK: Yeah, it is. And I like thinking about it as part of the fun. I finished writing this book in 2024 and it's going to come out in 2026. And the way the world has changed in those couple of years — I hope it still speaks in the same way to readers. But, yeah, you never know.

RS: How much do you think about that as you write? How much do you think about how your book will be received, whether it's by an individual reader or by readers as a group or by librarians and teachers? How much do you think about the audience?

TK: I suppose in the beginning I'm not thinking about that too much, or at least I'm trying very hard not to think about that. I'm really trying to figure out what the shape of a story is and who the characters are. And that takes up so much brain space. I’m trying to figure out the puzzle of a story so I’m not thinking about a reader yet, or at least not specific readers. I'm always thinking about what I want to say generally in response to the world, but it’s not until later revisions that I’m really thinking about a kid reader. And sometimes that's on a line level, just making sure that a line is clear, or if I use a reference, making sure it’s a reference that would make sense to kids — specific things like that. But also just making sure that I’m clear about what I’m trying to say to kids. Because I feel a lot of responsibility as someone who writes for children, someone who puts something out into the world to say, “This is my contribution to the conversation.” I want to make sure that I’m contributing in a way that helps someone.

RS: How far along do you get before you share that book with an editor or your agent?

TK: It depends. I showed my editor the first third of this one when I was stuck, and she was really helpful. But typically I’m maybe eight drafts into my twenty before I’m sending it to my editor. My husband is my first reader. He sees not all twenty drafts, but half of them. And he’s great. He’s not a writer himself, but he’s very analytical and thoughtful. And at this point we’ve discussed stories together so much that he knows what I am trying to do when I am writing, and he knows how to give feedback to me in a way that will be useful.

RS: Because you are trying to communicate, right? So you might write something that seems beautiful and incisive and brilliant to Tae, but at some point — and you want to do this before the book is published — you’ve got to have someone who can say, “Wait, I don’t know what’s going on in this scene.”

TK: Exactly. Just someone with a different perspective and lived experience to be able to read something and say, “Oh, actually, my interpretation of this is completely different.” That’s so helpful to know before the book comes out.

RS: Someone who is approaching the book as a reader, not as the writer.

TK: Yes, and someone who's not completely in the weeds of the story. Who can see the forest for the trees.

RS: How do you keep track, from draft to draft, of what you’re going to keep and what gets jettisoned?

TK: Part of the reason I do so many drafts is because I’m usually focusing on a specific element in each revision. So that helps me keep things clear. For this book, I did a revision separately for each character. So, obviously, focusing on their own chapters, but then also what they're saying in someone else's chapter. To make sure that each character's arc is really clear and that I'm not getting totally muddled, keeping track of three different characters.

RS: And keeping them distinct. That can be my bugnear when I'm reading books, particularly when they're narrated by different characters. Like you've got two narrators, you've got four narrators, but they all sound like the same damn person. So if you're going to do this, you know, make sure you keep them distinct.

TK: Yes, totally. That was part of the challenge and also part of the fun in having these three characters. And the book is in third person, so it's not maybe quite the same level of challenge as doing it all in first person. But more just making sure that each character has a different lens they see the world through and making sure that all the things they're thinking are filtered through this specific lens.

RS: And also, just practically, giving them enough individuality in terms of their story, what's happening to them, what they're thinking about, and having them interact — I would think you'd want to have a certain balance in that.

TK: Yeah, for sure. I have a corkboard that has all of these different Post-its and strings, like literally.

RS: Like a crime board.

TK: Exactly.

Sponsored by

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!