Yuyi Morales Talks with Roger

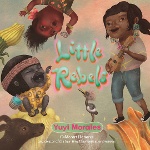

Inspired by her own community advocacy for the environment in the Mexican town where she lives, Boston Globe–Horn Book Award winner (for Dreamers) Yuyi Morales explores what it can mean for children to be Little Rebels, both dreamers and doers.

Talks with Roger is a sponsored supplement to our free monthly e-newsletter, Notes from the Horn Book. To receive Notes, sign up here.

Sponsored by

Inspired by her own community advocacy for the environment in the Mexican town where she lives, Boston Globe–Horn Book Award winner (for Dreamers) Yuyi Morales explores what it can mean for children to be Little Rebels, both dreamers and doers.

Roger Sutton: How do you write about big issues — like, for example, drought in this book — for little kids without scaring them?

Yuyi Morales: I take a lot of care because I am usually scared. For me, bookmaking is the process of finding those places that sustain me. I am scared. Things are happening that even we adults don’t know how to deal with. So for me, making the book is a process of finding out what those things are that I hold on to. The powers-that-be expect us to give up. Expect us to be content with what we’ve got, or even be very pessimistic and think that there is nothing we can do. So that’s another thing that I try to dissipate from my life — that there is no hope — because then I will be falling into the trap that has been set for us. To feel like, “Okay, this is it. There’s nothing we can do.” So I feel that action is what must take place. And when I was making this book, I was thinking, We are asking children, who are little, to face these enormous challenges. And even we adults, I feel little in the face of big challenges. So what is that thing then, that we grab onto, that we hold onto to continue? I think it’s a little thing. For years and years, I have explored how I’m always frozen when I have to start a book because it feels like such a big task. And again and again I realize that if I start little, I can do it. I just put away my big expectations and start with a little thing.

Yuyi Morales: I take a lot of care because I am usually scared. For me, bookmaking is the process of finding those places that sustain me. I am scared. Things are happening that even we adults don’t know how to deal with. So for me, making the book is a process of finding out what those things are that I hold on to. The powers-that-be expect us to give up. Expect us to be content with what we’ve got, or even be very pessimistic and think that there is nothing we can do. So that’s another thing that I try to dissipate from my life — that there is no hope — because then I will be falling into the trap that has been set for us. To feel like, “Okay, this is it. There’s nothing we can do.” So I feel that action is what must take place. And when I was making this book, I was thinking, We are asking children, who are little, to face these enormous challenges. And even we adults, I feel little in the face of big challenges. So what is that thing then, that we grab onto, that we hold onto to continue? I think it’s a little thing. For years and years, I have explored how I’m always frozen when I have to start a book because it feels like such a big task. And again and again I realize that if I start little, I can do it. I just put away my big expectations and start with a little thing.

RS: What was the little thing you started with this book, with Little Rebels? What was the germ, the seed, of it?

YM: There were many. And I think that's what made it a little difficult. I didn't even know where to begin. I knew I wanted to write about certain things. I went to my therapist and said, “I have no idea how to even begin telling this story,” and she responded, “Well, how about there is no one way to start anything? There are infinite ways. There are many, many ways.” And that's why in the book I ask, “How to begin?” And that was a real question I had in my mind.

RS: Asking yourself.

YM: Yes. So I began with not an answer that I give all by myself alone; I begin with an answer that I find in different places because I find many different answers. That's something that has become very important to me: to be pluralistic. There is not one single way of doing anything. There is no black and white; there is no male and female. There is nothing that is just binary, but in fact it’s more like infinite. But you were asking me about the seed for this book. I think it started during the COVID pandemic, when we were isolated and, at least here in Mexico, had to stay at home. And I was thinking about community. There was this feminist Spanish woman who was talking about how real love, which we are always looking for, is a love of community, it's a love of your friends, and how we usually give it second or third or even last place in a ranking of affections.

RS: After your partner, after your children, after your mother.

YM: Yes, exactly. And it was a time when I was alone, with my partner, but somehow alone. And I remember wondering, How do we create community when we are so isolated? I started thinking, If I want to create a community in this place where I’m living, how do we do it right now if we cannot gather together? So I start reaching out to some friends, especially some feminist friends. Even though it was the pandemic, they were organizing and gathering and doing things, and the way we started is that we made a community mural. We made a community mural, and it was the first time that I made something over which I had no control. It was not my creation. It was making art that was not just me at my desk.

|

| Community mural. Photo courtesy of Yuyi Morales. |

RS: In your head.

YM: Oh, yeah. No, it was completely different, and the process was so beautiful that I’ve begun working more with them. We’ve made three murals over the years we've been working together and organizing ourselves. And that's when I began learning things. We go through things that are painful and we look for ways to fix them. Like if I'm hurt, I might take a bath, or do yoga, or come to a place where I don't have to deal with everything else, but that doesn't really heal me because as long as the rest of my community is still going through difficult things, then the healing won't happen.

RS: You won’t feel any better.

YM: No. Because what is hurting us is systemic. And that’s why we are losing our resources. It’s affecting our community, our environment, the place that is our home. What’s hurting us is much, much bigger than any of us. And then, yeah, we are little. And so how do we do it? And then the other thing that happened is that I came to the beach, to La Mancha. That was also during the pandemic. I was looking for a place where I could take my mask off. I had finished my book Bright Star and I was able to finally come out of my studio, and I found that everything around was closed, so we came to the beach. We came for a weekend, and I didn’t want to leave. I thought, “I just want to stay here.” My son doesn’t want to come visit me here because we are riddled with mosquitoes and it’s really hot. But I love it. I do. And I am just a couple of kilometers from a lagoon that I visited with my family when I was a child. My father brought us because he had friends here. They were fisherpeople and so they brought their wooden boat and they fished. I remember being very impressed — they would catch a fish and it was still alive and they would start cleaning it and the fish was still moving around. That was hard. But that was the experience in this lagoon. And this lagoon is only a mile from where I live in La Mancha. But by now it was completely dry, absolutely dry. I think that started something in me even though I didn't know it at the time. I'm finding out that La Mancha is not only a beach town. It is a very ecologically important place in the world. This is one of the biggest corridors for migratory birds of prey — we call them aves rapaces — in the world. And yet it is being depleted. The forest is being cut. And we are currently fighting against a chicken farm, a megafarm that has been installed here. It comes from the United States.

RS: As all good things do, Yuyi, remember that.

YM: Yeah. So everything that comes from the chickens and from their production goes into a creek that feeds straight into a nearby lagoon (a different one). We are fighting against it. And we don't seem to be winning. So when you have those things to deal with, I do feel very small. But I know that I have my community. And with that, we become a little bigger. And our actions become a little more significant. We don't know if we are going to win, but we are still working on it. And in the middle of all that, I began making this book. My collective was protecting trees that they were cutting down in the city to make a freeway. And I went there with my friends and I didn't leave until six months later. They set up a campsite where people would spend the night there. I almost never spent the night there, but I was mostly there during the day, and I was making Little Rebels. So I would sometimes bring my sketchbook or my iPad, and I was able to do some work while we were there guarding these trees and making sure that they wouldn't come and cut them down.

RS: What’s it like to create art in the midst of doing something like that?

YM: It was very difficult. In fact, I think my editor Neal Porter was a little fed up with me because he kept asking, “So when will you have something for me?” I wasn't physically producing much because sometimes I’d be working on it and then I would have to stop because the workers were coming and we all had to run to be in front of the machines. But I think that maybe my drawings weren't getting done, but something else was getting done. What I was doing there was finding out where our power comes from, where our strength comes from. And in the middle of that, trying to make a book for children.

RS: Do you and Neal talk about how a child will read your book?

YM: We talk some, but mostly he's very hands-off. He trusts me. And then at the end, it’s his time to say, “You know, Yuyi, this is going to be difficult for a child to understand.” He’ll say, “Imagine I'm just five years old and I have all these dumb questions. Can you help me understand this?" And then we work together. He's very good at it.

RS: I was thinking, as I read Little Rebels, that despite the title it’s kind of an etiquette book. It’s a book about how to behave.

YM: Yes, you're right. I’ve belonged to this writer's critique group for more than two decades now. And when I first presented the book to them, one of the reactions was that they couldn't understand my definition of rebel. They said, “When we think of rebels, we think of someone who’s going to fight and someone who might have weapons and someone who might hurt you and someone who you cannot control, and that’s not a good thing.” So then, rather than trying to explain what a rebel is, I try to explore what it is that I'm trying to find. And just last week, I was talking to a friend, one of the friends that I met when I started making those collective murals. And I was telling her that because my book is out now, I find myself in the position of having to answer, “What do you mean by Little Rebels? Isn't that a bad thing? When I was a child, my mother would not have wanted me to be a rebel at all. So what are we telling children?” And what my friend said is, “You know, Yuyi, the place of the rebel and the idea of a rebel is a territory in dispute.” That's what she called it. “A disputed territory.” Because we are all trying to find what kind of rebel we are. Other people can say, “No, being a rebel is being a terrorist” or “No, being a rebel is like understanding how to behave” — as you say, etiquette. When I began knowing these women and working with them, we knew we were trying to break with a thing that has been inherited by us, which is how we do things, how to behave, how to be very individualistic. So when we are rebelling, we are rebelling against all of that. I had to unlearn so many things and make space for a different way of understanding the world and how I relate to other people. And I also learned that there is no way of organizing ourselves that will yield real results if we don't do it with affection. If affection and connection are not at the core and the heart of why we get together, then things are not going to work. We are going to break apart. We are going to have even more problems than we have now because even in chosen relationships, we still have to work out how we connect with one another. But it is only when we do it through connection and through affection that we can really learn a different way of being with one another and with our world. So that's what I think: rather than saying how to behave, it is more of an invitation to unlearn what we have been taught. And what will happen if we do it differently? We stop saying that what we want is to be the best, to compete and see who can do it better. What if, instead, we just concentrate on getting things accomplished all together and for the wellbeing of everybody?

RS: That is a way of behaving, right? It’s just a different way of behaving.

YM: It is a different way. Now, what will happen, Roger, if we take it out of the behavior box and we think of it as something different? We can even give it a different name. That's another thing that I love exploring in Little Rebels, which is that words also shape our world. Depending on how we name something, then that is how it functions, it’s how we see it, it’s how we take care of it, or fight against it. So giving things and actions the names that work for us and for our intentions and for what we are building is also a way of being a rebel and building and shaping the world that we want. So that’s why I’m thinking that rather than call it behavior, we can call it something else. We can call it discovery, or even...

RS: Attitude.

YM: Or we can make up a new word.

RS: I love the sentence in the book: “When we need a different world, we invent new palabras.” I loved the way that you just slipped into Spanish from English as a way to demonstrate your point. I thought that was brilliant.

YM: Thank you. I love putting Spanish in there because it’s a way to honor my native language. But it’s also a way of speaking. People often ask me about the picture book and how it's made of words and it's made of illustrations. And I always say, “Actually, it's made out of a lot of ways of things, you know, we make many languages there. If you see English, you see Spanish, you see color, you see page-turning, you see positioning, you see everything — there are lots of languages happening there.” And so then when I put a word into the book in Spanish, or even a made-up word (which sometimes Neal lets me, sometimes not), then I'm finding even more languages in which to say what I want to say in the book.

RS: In the Spanish edition of the book, do you remember how you did that sentence?

YM: I don't do my own translation. We always work with a translator, even though Spanish is my native language, because I always write in English first. When I began trying to write stories, I was already in the United States and I was trying to learn to do it in English. So now for the Spanish editions of my books, they always use a translator. And it’s amazing, because it is another voice that comes into the story. For this book the translating was difficult, because Spanish nouns are gendered, feminine or masculine. But one of the things that I wanted for this book was to use inclusive, non-gendered language in Spanish, and that was hard. But this is a book about little rebels. So for me, it was very important. And that was a challenge. But the translator did such a good job. Really, really. She made sure that she was saying the same thing I was trying to say with other words that didn't have to do anything with gender, so it was perfect.

RS: To me, Little Rebels feels like a family book. You could even use this with babies. I mean, the text is going to go over their heads, but they’d love the pictures. They'd love seeing the children interacting with each other and then as they get older you can talk about the ideas. It's a book that I think needs conversation to go with it.

RS: To me, Little Rebels feels like a family book. You could even use this with babies. I mean, the text is going to go over their heads, but they’d love the pictures. They'd love seeing the children interacting with each other and then as they get older you can talk about the ideas. It's a book that I think needs conversation to go with it.

YM: I think you're absolutely right. I strive for that. I don't put in a lot of details, but the details that I use, I think, are meaningful, at least I tried to make them meaningful. For instance, when the kids in the book are putting things inside of a little bag that they are going to bring for their adventure, they include a little cake, kind of like a rice cake.

RS: Yeah, I thought it was a rice cake.

YM: Yes, but it's not a rice cake, it's made out of amaranth. It's called alegría, which means happiness. And it’s very traditional in Mexico. That’s one of the things the children bring to share. They are bringing a piece of happiness. And then of course they bring crayons just in case they need to do art, to express themselves. And then something to give thanks — a sahumerio, which is what you put incense in and use to give thanks. And as I told you, we are fighting the chicken farm, and we were fighting to protect the trees. And part of that fight is always spiritual strength. Sahumerio are always part of the altars or part of ceremonies, so at some point we will go and give thanks and ask for strength. That’s why it was important for me to put a sahumerio in the book, because the connection with the spiritual is an important part of any fight or any endeavor, especially a community endeavor. All children might not recognize these items or know what they are about, but there are some that will and to them this is like maybe a wink. But at the same time, it’s opening windows to other ways of doing things.

RS: It also allows you to ask a child, “What would you bring?”

YM: Exactly. What I'm really hoping is that there are going to be a lot of questions like that. “What would you ask? What would be your questions when you just met someone? What will you bring to your adventure? Will you be a little rebel?” Because we all have our very own ways of doing it. We don't all have to go hug a tree so they don't cut it down, but we have our own ways of protecting and changing our world. I hope that that question is going to be asked when the reading happens. Like you say, yes, I hope that children if they open it all by themselves are going to be curious and check out what is happening, but if there is an adult reading with them I hope that mostly there are going to be questions, and questions that have no right or wrong answer, but just to explore what children have inside. One of the things that is very important to me is that we take the adult out of the center and we start asking children for their wisdom, the things that they know and the things that they can teach us so that we can learn from them. Let's stop trying to be the ones who are trying to change them and teach them what they should know. Let's be the students.

RS: What’s it like as an artist, particularly an artist for children, to be in communion with a reader you never meet? Generally, you won't hear the other side of the conversation. But you know that there's one happening.

YM: Yes, I know. And that is hard, because how do you know that children are even getting what you thought that you were trying to tell them? My first book was about a skeleton. I had a hard time placing that book. I had a lot of responses from editors, and they would say, "We really like your illustrations, but we are never going to be able to sell this book." It was scary. So when the book was finally published and I started visiting schools, one of the things that I did was ask children, "Are you scared of Señor Calavera?" And they usually said, “No, of course not.” And then they would have suggestions about who Señor Calavera was. They would say, “Oh, he's a friend, he's a companion.” And someone would tell me that I should marry him. So what I realized is that every child will take from the story what they are ready to take from the story. And no matter what our intentions are, at some point it’s out of our hands, right? And then the reader will take what serves them and just skip what they don’t understand. But as they grow older, they start asking questions. So while I say this, I also want to make sure that we are always careful with what we bring to children. It will be in the hands of children who have their own experiences, who have perhaps gone through their own traumas. And so I think that's when our work begins. It's not so much if our illustrations are good or our writing is good. I don't think that's the most important thing. The most important thing is something that we learn along the years and going along the road, which is how we take care of our children through the work that we do.

Sponsored by

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!