Saadia Faruqi Talks with Roger

A supporting character in Saadia Faruqi’s popular series about Yasmin (from Yasmin the Builder to Yasmin the Zookeeper, with eighteen books in between thus far), Ali Tahir is another Muslim-American second grader with a big imagination. Now he gets his own series.

Talks with Roger is a sponsored supplement to our free monthly e-newsletter, Notes from the Horn Book. To receive Notes, sign up here.

Sponsored by

Capstone Publishing

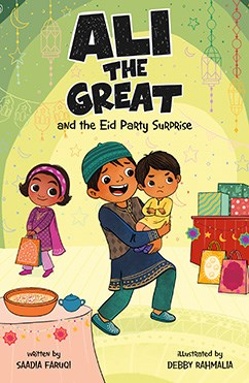

A supporting character in Saadia Faruqi’s popular series about Yasmin (from Yasmin the Builder to Yasmin the Zookeeper, with eighteen books in between thus far), Ali Tahir is another Muslim-American second grader with a big imagination. Now he gets his own series, starting with Ali the Great and the Dinosaur Mistake, Ali the Great and the Eid Party Surprise, Ali the Great and the Paper Airplane Flop, and Ali the Great and the Market Mishap. Saadia and I talk below about early readers, religious representation in books for children, and the question that will not die: What do we mean by “a boy book”?

A supporting character in Saadia Faruqi’s popular series about Yasmin (from Yasmin the Builder to Yasmin the Zookeeper, with eighteen books in between thus far), Ali Tahir is another Muslim-American second grader with a big imagination. Now he gets his own series, starting with Ali the Great and the Dinosaur Mistake, Ali the Great and the Eid Party Surprise, Ali the Great and the Paper Airplane Flop, and Ali the Great and the Market Mishap. Saadia and I talk below about early readers, religious representation in books for children, and the question that will not die: What do we mean by “a boy book”?

Roger Sutton: Let’s talk about Ali. As I was reading his stories, I thought about how some of the most revolutionary books we see are the quiet ones.

Saadia Faruqi: There’s something to be said about a quiet story that simply reflects life for a kid, with parents, grandparents, friends, siblings. It doesn’t constantly have to have some big drama going on. Ali is involved in a lot of small dramas, though, so it’s not as if there’s no fun to be had.

RS: You have to have drama, or you won’t have a story.

SF: Absolutely.

RS: This is a companion to the Yasmin series you started in 2018?

SF: Yes. There are twenty books now. I’m grateful to all my readers, who have made it such a big success. Kids read these books all over the world. Ali is a side character in the Yasmin books. He’s a friend in her class, and now he’s got his own series. It’s still the Yasmin world with the same characters, but the stories are more about Ali’s family and his antics; he’s the star of the show, and very different from Yasmin.

RS: What was the impetus to create a new series, rather than just keep going with Yasmin?

SF: We are still going to keep going with Yasmin. She’s just taking a break. She’s tired out from all her adventures. But the impetus was my readers. When the Yasmin books came out, they were successful, but I started getting requests for quote-unquote boy books. I remember the first time somebody walked up to me at a book signing—I think it was a mom of boys—and she said, “We love Yasmin, but can you write a book for boys?” I looked at her and said, “Your boys can read Yasmin.” Girls read books about boys all the time. Why is this a thing? I continued getting questions about when I was going to write a boy book. The requests were always from adults; no kids ever asked me, “Can you write about a boy?” It was teachers, librarians, and parents. I kept telling them, read a Yasmin book; you’ll love it. Then after a while, I realized I was doing a disservice to my readers. I have two business degrees, and my books are my product. If my customers want something, I can’t keep saying no to that just because I have an issue with it. I said to my editor, “What do you think about my writing a book about a boy that’s like the Yasmin books and see how it goes? If it doesn’t work as well, no need to write a whole lot of them.” She agreed it was a good idea.

RS: I look back to Horn Book magazines from the 1920s and ’30s; even a hundred years ago, people were fighting about boy books and girl books.

SF: I have a boy and a girl of my own. They’re teenagers now, and I’ve seen how my son has stopped reading as much, while my daughter still reads. My son, who’s a senior in high school this year, told me when he was in middle school that he didn’t take out a library book because it had a girl on the cover, “and my friends make fun of me.” He didn’t think there was anything wrong, but he didn’t want the comments. He read those books at home.

RS: In fourth grade, my favorite book was a novel called Mary Jane by Dorothy Sterling. It was about a young African American girl and her friend, who were the first Black students at their high school. But the grief I got from other kids—boys, mostly—“Oh, you’re reading a book about a girl. What a sissy.” That was more than fifty years ago.

SF: I don’t think things have changed a lot. In fourth grade, maybe it was more of a joke, but in middle school or high school it’s bullying about gender expectations and worse. It’s sad, and that’s why I resisted it for a long time. I also thought, There’s a market, people who want something, and I can give it to them in a way that’s important to me. Ali was a character I’ve always wanted to explore because he’s so much fun, and he’s got a lot of potential. We decided to write a whole series where people still get Yasmin, and they still get that whole Muslim American family, South Asian family, and stories of friendship and intergenerational relationships. It’s a very similar book, but something for boys.

RS: It is something for boys, of course, but the Yasmin books are also for boys, and Ali is also for girls. Kids who are fans of Yasmin will just be happy about more stories in that world, like you said before.

SF: I hope so. Especially at that age. These are early readers, kindergarten through second grade, maybe third grade. The kids don’t care that much. Like I said, every single request I got, and I got so many over the last four or five years, were all from adults. They were right, in that I mostly gravitate toward writing girl characters. My first boy main character was in my middle grade novel Yusuf Azeem Is Not a Hero, which came out in 2021. I had written a good twenty or so books before I ever tried writing a boy main character. I think overall it was a message from the universe.

RS: I’m sure this series will have, as Yasmin has, readers who are Muslim and readers who are not. How do you think about those audiences in your mind as you write?

SF: For me, there’s not a big difference. I write authentic stories that I hope will appeal to everybody. Yasmin is based on my daughter when she was little, and her family is based mostly on my extended family. I’m presenting an authentic picture of life in my family (or in families like mine). The hope is that even if you’re not Muslim or an immigrant, you’re not South Asian, you still can find something to connect with, whether it’s going through the market with your grandfather, or having an annoying younger sibling that you are responsible for. I don’t think separately of readers who are Muslim or readers who are not. I want to write the best possible story for all my readers. If I’m making something up one group will enjoy and the other won’t, one group will understand and the other won’t, then I don’t think I’m doing a very good job. I want to make sure that I’m appealing to all of them in some way or another.

RS: Faith is important to many people, obviously. For young children, it can be a big part of their life, going to church, going to mosque, going to synagogue, whatever it is. We so rarely see it in plain old realistic fiction for children, like you’ve written here.

SF: For younger kids.

RS: And even for older kids. You don’t get characters going to church much.

SF: My middle-grade novels focus on the religious aspect of life as a Muslim. In my books for younger kids—the Yasmin books, the Ali books, even my chapter-book series, Marya Khan—I include the cultural parts of being Muslim. Someone’s wearing the hijab, or Baba’s got a beard, or they’re speaking Urdu once in a while. I think that when you’re five, six, seven, you don’t need to necessarily have a story line that includes something happening actively in a religious setting, but you can still have that background. When you go out, Mama’s going to wear her hijab. I’ve been—I don’t want to say brave; maybe just putting myself out there a bit more—in the Ali series. Ali the Great and the Eid Party Surprise is a story based on a religious situation. Eid is the big Muslim celebration after Ramadan. Ali’s family goes to the mosque, they pray, and then they go home and have an Eid party. It’s very different from what I’ve done in the Yasmin books. That was me taking a little bit of a risk that my younger readers would be okay with it.

SF: My middle-grade novels focus on the religious aspect of life as a Muslim. In my books for younger kids—the Yasmin books, the Ali books, even my chapter-book series, Marya Khan—I include the cultural parts of being Muslim. Someone’s wearing the hijab, or Baba’s got a beard, or they’re speaking Urdu once in a while. I think that when you’re five, six, seven, you don’t need to necessarily have a story line that includes something happening actively in a religious setting, but you can still have that background. When you go out, Mama’s going to wear her hijab. I’ve been—I don’t want to say brave; maybe just putting myself out there a bit more—in the Ali series. Ali the Great and the Eid Party Surprise is a story based on a religious situation. Eid is the big Muslim celebration after Ramadan. Ali’s family goes to the mosque, they pray, and then they go home and have an Eid party. It’s very different from what I’ve done in the Yasmin books. That was me taking a little bit of a risk that my younger readers would be okay with it.

RS: Ali is experiencing that holiday from a child’s point of view. It’s not the author explaining to readers what this holiday means. We see him with his little brother, getting into mischief. You’ve got your own Ramona in training there, I think, with that little brother.

SF: That’s very important to me as a writer. I try not at all to explain things. I just try to paint a picture, and most kids, with context clues, or adults who read the book with them, will get it. If you don’t get it, Google is a friend, I guess. Every Capstone early reader has back matter, so The Eid Party Surprise explains what Eid is and why we celebrate it. It’s there, but it’s not part of the story. Like you said, kids who go to church or synagogue or anywhere, they all can identify and don’t have to really wonder about what’s going on at a mosque or what happens at Eid. It’s the fact that you have a little sibling, he’s trying to run away, and you have to deal with it. All of those things are similar experiences, even if we might be different religions. That’s my aim with all of my writing. When you peek into someone’s life, you realize that there are more similarities than there are differences. Relationships are the same no matter what religion you are or what culture you are.

RS: What was your children’s schooling like when they were Ali’s and Yasmin’s age? What kind of mix was it?

SF: Diversity-wise? We were in Houston, which is very diverse. Houston is international, different people from different parts of the world live here. My kids go to a charter school, which is very, very diverse, maybe 99.9 percent people of color around them. It was important to me to make sure that my kids had that background where they not only were able to get exposure to different groups of people, but they didn’t stand out as the only brown kids in the sea of white. I think that’s benefitted them. I think we all learn so much from other cultures and other religions.

RS: You were still in Pakistan when you were in second grade, right?

SF: I was, yes. I came to the U.S. when I was twenty-two years old.

RS: What did little kids in Pakistan read then?

SF: Obviously, Urdu books. Urdu is the main official language there. I grew up in Karachi, which is very much like New York in terms of being very cosmopolitan, very big. I read books in Urdu, and I read books in English. I went to a Catholic primary school and our education was all in English, so I gravitated more toward British books, because Pakistan was a colony of the British empire until 1947. I didn’t read an American book until—I think I read Sweet Valley High or something similarly lightweight.

RS: That must have seemed exotic.

SF: We watched American movies, so we knew what was what. When I was very little, it was mostly very old British books.

RS: Was there a lot of publishing for children in Pakistan, then or now?

SF: I don’t know about now, because I haven’t lived there for twenty-five years. The publishing was all Urdu and Arabic, I think. I could read Urdu, but I wasn’t fluent, so I gravitated more toward books in English because that’s what I was reading for school. Pakistan has a book market, and India, which is right next door, has a wide-ranging publishing landscape. I love reading, and I used to write stories in my notebooks. I was really into storytelling, not just books, but stories my grandma used to tell me, stories on TV, things like that. I loved that world of creating something that would entertain other people.

RS: I have friends from South Africa, India, Australia, all former British colonies, who also, like you, grew up with British books. That world was so different from what they saw in their day-to-day lives.

SF: I think that when you have TV and cable, it’s not that different. I read books where kids were eating, say, ham sandwiches, and I’d think, What the heck is that? We don’t have ham in a Muslim country. That sounded gross to me. There were words that I didn’t know, and I looked them up. If you’re a big reader, it’s the same as a non-Muslim kid in the U.S. reading an Ali book. They may think that it’s different at first, but then you get into it and realize that this is a great story; I don’t care what language they’re speaking, or what food they’re eating. I just want to be entertained by the story. That was my takeaway, even when I was reading a book about a different culture.

RS: How do you keep in touch with what second graders like?

SF: When my own kids were younger, a lot of my books were about things that happened to them in school. Now it’s a little bit more challenging. I talk to people who have younger kids. Teachers and librarians support me a lot. I visit schools for author visits. I’m constantly making sure I stay in touch, reading other people’s books. And you know what the editorial process is like. My editor at Capstone, Kristen McCurry Mohn, is amazing. She always has great feedback. She’s happy to step in and remind me what it was like when my kids were seven.

RS: I think just as a Muslim kid’s experience in America is the same as a Christian kid’s experience in a lot of ways, that similarity also occurs over time. When I talk to the little boys who live downstairs, I can definitely see myself sixty years ago.

SF: I feel like the experiences, the feelings would be the same. How you feel when you’re seven, versus how you feel when you’re eight or nine or twelve, I don’t think that changes. As a writer, I love exploring those different ages, what emotions you get at a certain age, and how you learn about the world around you, what role friends can play, and families can play. I love those discoveries and writing about them.

RS: As adults, we can look back and squish it together, but as children, the difference between seven and eight, when you’re seven and eight, is huge.

SF: For sure. Eight comes around third grade, and you get a lot more jealousy, a lot more competitiveness. “He’s got this, and I don’t have this.” I always tell my kids that third grade is a big deal. Before that you’re still little, hanging onto your mom or dad or your teacher. Starting in third grade, you want to go your own way.

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!