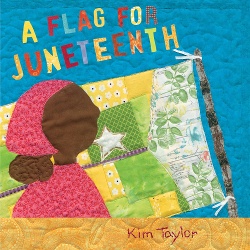

Adrienne L. Pettinelli discusses how the quilted fabric collage illustrations in Kim Taylor’s A Flag for Juneteenth are so resonant and an ideal match for the subject matter.

I am fortunate to have quilts made by my Italian-American great-grandmother. She used scraps of the fabric from the dresses she sewed for her four daughters to make crazy quilts, though she delved into patterns, too, when her girls were older and her life less frantic. These quilts teach me that my love of vibrant color and pattern are perhaps inherited traits, and especially when I was a child, I loved looking at the fabrics in the quilts and imagining what types of dresses they made and which sisters wore them.

I am fortunate to have quilts made by my Italian-American great-grandmother. She used scraps of the fabric from the dresses she sewed for her four daughters to make crazy quilts, though she delved into patterns, too, when her girls were older and her life less frantic. These quilts teach me that my love of vibrant color and pattern are perhaps inherited traits, and especially when I was a child, I loved looking at the fabrics in the quilts and imagining what types of dresses they made and which sisters wore them.

To hold a quilt is to hold history — it’s inherent in the medium. Walk into anyone’s house and notice the quilt displayed on the wall (sorry, Alice Walker) or tossed over the back of a sofa, and you’re going to get a story about who made it, when it was made, and why it was made.

This is part of why the quilted fabric collage illustrations in Kim Taylor’s A Flag for Juneteenth are so resonant and an ideal match for the subject matter. This is the story of Huldah, who turns ten on June 19, 1865, the first Juneteenth, the day her family learns about the Emancipation Proclamation and their freedom from enslavement. Huldah’s enslavement is not the focus here — we see her as a cherished child in a loving and supportive family and community. The story, like the fabric in the collages, is layered.

Let’s look at these collages. Quilted backgrounds create the settings for raw-edged applique figures in the foreground. I love the choice of raw edges for this story. Juneteenth is not a simple celebration — it is a celebration, yes, but one born of horrors with consequences that reach into today. The raw edges speak to how raw these emotions are for so many people, and they remind readers that these illustrations are handmade and labored over. I have spent time examining the stitching, trying to decide if the sewing is done by machine or by hand, and my determination is that it’s probably both — either that or Taylor has the most perfect hand stitches I’ve ever seen, which is possible. I see hand work in the occasional irregular stitch or hanging thread. This isn’t meant as criticism. To me, this art is distinctive because it doesn’t feel the need to be perfect, because it accepts the dissonance of celebration sitting next to grief, and because it has this beautiful folk art vibe. Quilting and sewing are domestic arts — born of practicality but producing items that are passed down, like stories, from generation to generation. These arts have been important forms of self-expression in the Black community, evidenced in the book by the women in Huldah’s community sewing freedom flags for each member of the community to celebrate the profound change in their lives.

Taylor’s characters’ faces are blank silhouettes with no facial features. Instead, she expresses characters’ emotions through composition and color. A wonderful example is the spread illustrating “I squeezed through the crowd, listening as people prayed, sang, and cried quiet tears of joy.” Huldah is on a quilted ecru background on the left-hand side of the spread with the text, witnessing but slightly removed. On the facing page, five figures are on a quilted background in various states of joy and praise. First, pay attention to the quilting, which functions as line work. The bottom is freehand squiggles, but then the quilting on the top half radiates out like the sun — a subtle way to indicate joy and openness. The figures themselves are silhouettes in various postures. Four have their hands raised, two are on their knees. One or two look like they may be jumping in the air. And then we have one figure in a posture of supplication and prayer. All of this is done in vibrant fabrics — a plain sunny gold background with figures in patterned red, blue, orange, and green. Even without the text, we see the jubilation but also complexity in the emotional reactions. We see Huldah’s struggle to understand and figure out how to join in.

Holiday books have a spotty track record as Caldecott winners and honors — there have been some, but not many. Fabric art has almost no representation in the Caldecott canon, aside from some pieces in a personal favorite of mine, Viva Frida by Yuyi Morales, which earned a 2015 Caldecott Honor. Recent Caldecott committees have demonstrated a willingness to depart from tradition and move more boldly into what I think of as more holistic and novel interpretations of the Caldecott criteria, but, still, tradition is a powerful force that could keep this book from being considered the way I hope it will. A Flag for Juneteenth is distinguished both by virtue of quality and by virtue of being different from the other picture books in front of us this year, in terms of medium, subject, and complexity that remains age-appropriate. Regardless of what happens with the Caldecott, I hope this beautiful book is read in homes, libraries, and classrooms for years to come.

[Read The Horn Book Magazine review of A Flag for Juneteenth]

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!