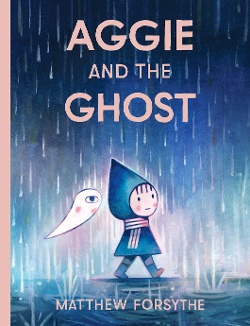

"Each image is a kaleidoscope of colors, beautiful to look at, while also exuding a calm energy that works in concert with the dry wit of the text." Adrienne L. Pettinelli considers Matthew Forsythe's Aggie and the Ghost.

When I was in the fifth grade, our teacher, Mrs. Maleski, had the class keep journals, which she periodically collected and graded. I still have my journal, a classic black-and-white marbled Mead composition book. My personality is fully-formed in its pages—my preoccupation with my pets and what I was having for lunch, my intolerance of wet socks, my focus on getting a decent night’s sleep. (Even at the age of eleven, I was like, “I was up until 10pm, and it was the worst.”)

When I was in the fifth grade, our teacher, Mrs. Maleski, had the class keep journals, which she periodically collected and graded. I still have my journal, a classic black-and-white marbled Mead composition book. My personality is fully-formed in its pages—my preoccupation with my pets and what I was having for lunch, my intolerance of wet socks, my focus on getting a decent night’s sleep. (Even at the age of eleven, I was like, “I was up until 10pm, and it was the worst.”)

It was around this time that it dawned on me that there was power in the written word, a power I might use. In this case, I decided to try to use it to wage a campaign in my journal to convince Mrs. Maleski to move me from my assigned seat near three boys who I repeatedly describe as “revolting” to a seat near my friends Roxanne, Jessica, and Tricia. Aggie and the Ghost by Matthew Forsythe deals with this common childhood (and, frankly, adult) dilemma: how to cope with those we wind up in proximity to whom we would not have chosen.

“Aggie was very excited to live on her own.” Until, that is, we learn on the page turn that Aggie’s charming mushroom-shaped bungalow comes with a teardrop-shaped, one-eyed, singularly irritating ghost. The ghost follows Aggie around, interrupts her sleep, steals her socks, and eats all the cheese. “Revolting!” my child self cries.

Caldecott asks us to consider “excellence of presentation in recognition of a child audience.” Forsythe sets his drama in a fairy-tale-like setting, creating cozy harmony in illustrations that blend watercolor, gouache, and colored pencil in earth tones shot through with rich shades of red, yellow, and blue on creamy thick paper that enhances the soft texture of the mixed media. Each image is a kaleidoscope of colors, beautiful to look at, while also exuding a calm energy that works in concert with the dry wit of the text to create a story that’s engaging and funny but also thoughtful, humor that ends in a chuckle rather than screams of laughter. Forsythe creates a safe space in which this PITA of a ghost is exasperating, not scary—an entertaining space in which children can focus and think.

Speaking of space, the images in this book are minimalist in many ways—few full spreads, lots of spot images, plenty of white space—but they come off as pleasantly mellow rather than stark. This is partly due to Forsythe’s skill with mixed-media and color, but it’s also because he’s careful about the details in his compositions. For instance, we see images of Aggie running around with one sock on before we learn that the ghost is a sock-stealer. Aggie has a pot hanging on the wall of her kitchen, suggesting she’s cooking regularly and making an effort to have a comfortable home. Forsythe gives Aggie innocent-looking dots for eyes, while the ghost’s one horizontal oval-shaped eye (call it “The Jon Klassen Eye”) gives it a shifty vibe. Deliberate choices fill out the characterizations and move the reader through the story the way Forsythe intends.

Aggie is our point-of-view character here, and Forsythe asks us to empathize with her as she becomes frustrated, creates unrealistic rules for the ghost, and becomes frustrated again. What sets this book apart from many other stories is the way Forsythe also asks us to empathize with the ghost when it laments, “There are too many rules in that house, and I’m not good at following rules.” This leads to a fateful game of tic-tac-toe that will determine if the ghost stays or goes. In the pages that cover the game, we see Aggie’s and the ghost’s eyes evolve to mirror each other, first as horizontal, pointy ovals and then as identical dots, visually suggesting that these two are equals, both with realities and worldviews worthy of consideration. They are so equally matched that their game ends in a draw when the Man-Faced Owl (we don’t have time to get into that right now) swoops in and declares a tie.

In the aftermath of the game, the ghost becomes depressed by his inability to follow the rules and disappears one day. Aggie enjoys her peace for a while, but then she gets lonely. Her solution is as thoughtful, clever, and warm as the rest of the story. I hope this year’s Caldecott committee takes some time to get to know this distinguished and endearing book.

(End note: I am sorry to report that Mrs. Maleski never did change my seating assignment to my satisfaction; however, Roxanne is my friend to this day, and those boys and I became friendly, if never quite friends. Turns out revolting boys can be amusing.)

[Read The Horn Book Magazine review of Aggie and the Ghost]

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!