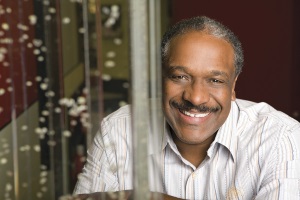

2024 CSK–Virginia Hamilton Award Acceptance by Christopher Paul Curtis

I am the father of three very young children: Ayaan, now thirteen, Ebyaan, now twelve, and my ten-year-old son, Libaan.

I am the father of three very young children: Ayaan, now thirteen, Ebyaan, now twelve, and my ten-year-old son, Libaan.

I am the father of three very young children: Ayaan, now thirteen, Ebyaan, now twelve, and my ten-year-old son, Libaan.

The differences in our ages are such that strangers frequently approach me and tell me how sweet and well behaved my grandchildren are.

This is not the sort of thing that bothers me.

I gave up all pretenses of looking youthful more than a decade ago when, on a trip to Texas, I was one of the final three people waiting at luggage carousel number four at the airport.

The other two stragglers were a squirming, whining four- or five-year-old girl and her harried mother, who had a kung-fu grip on the child’s wrist. [Photo: Daniel S. Harris Photography]

I remember thinking, “Ooh, I feel for that woman, that child looks like she’s all-the-way live!”

The little girl was even more restless than I was. She was peppering her mother with a million questions and was really through with the Dallas Fort Worth airport.

In a frustrated last gasp, she loudly asked, “Mommy, why is that old baldheaded man standing over there?”

To show how clueless I am: I looked over to carousel number three. Then over to carousel number five. No one was there.

I looked at the girl and her mother again.

It took much longer than it should have, but I finally figured out who the baldheaded old man was.

The mortified look on Mom’s face as she clutched the child to her chest while staring at me and mouthing “sorry” again and again explained everything.

That’s not the sort of thing that bothers me either.

I’m from Flint, Michigan. We’re tough. So, I wasn’t even bothered by the way I was notified about receiving this tremendous honor.

Even though it was through an act of chicanery and trickery, perpetrated upon me by a group you would never expect to be so well practiced in deceit: librarians.

I’d gotten a call from one of my heroes, Dr. Pauletta Brown Bracy, asking if I would be willing to do a Zoom call detailing the differences the CSK Book Award had made in my life.

Pauletta told me someone would notify me about setting it up.

When the day came, I was well prepared. I even had notes taped to the perimeter of the monitor so I could sound worldly and intelligent and, most importantly, spontaneous.

I even had a particular Toni Morrison quote ready to add to the conversation taped to the screen.

For tech backups I had my three children in the room.

The screen came to life, and I was quite surprised to see six or seven people crammed onto the monitor.

Even more surprising was that I recognized a friend, Chrystal Carr Jeter, who almost thirty years ago had been the first person to invite me to do a school visit in, of all places, Anchorage, Alaska.

And wasn’t that Pauletta in the upper left-hand corner?

Red flags flew immediately.

From question one there was something very off about the “interview.” It clunked along for a few minutes and then out of the blue the apparent ringleader of the group, Emma McNamara, announced, “Christopher, we’re sorry to tell you this, but we lied to you about the reason for this call.”

If someone was recording the call, I never want to hear it, because, totally bewildered, I stammered, hemmed, and hawed for a full minute while trying to process those words.

And yet, every one of the people on the screen seemed very pleased with themselves.

My eyes shot up to the upper left-hand corner of my screen where my hero, Dr. Pauletta Brown Bracy, was smiling and nodding along with the others.

I thought, “Et tu, Pauletta? Et tu...?” Who are these people?

I mean, I know Pauletta and Chrystal, but I hadn’t seen them in years. Who knew what kind of mischief they’d gotten into?

Especially that Chrystal Carr Jeter.

It wasn’t implausible that the FBI or the IRS finally had something on Chrystal, and she was using Pauletta as bait to entrap me.

Then Ms. McNamara told me what the call was really about: the CSK jury was bestowing upon me this tremendous honor.

I was relieved and overwhelmed.

When the call ended, I announced to my children, “Guess what? Your dad just won the Coretta Scott King–Virginia Hamilton Award for Lifetime Achievement!”

My middle daughter, Ebyaan, whose tagline is “No offense, Dad, but…” followed by a withering blast of the most offensive, eye-bugging remarks possible, said, “I guess that makes it official.”

I asked, “Makes what official?”

She said, “That your career is officially over.” The other two nearly died laughing.

That’s not the sort of thing that bothers me either.

How could it? I was about to share an award with the Mount Rushmore of African American writers for young people. Nikki Grimes, Mildred D. Taylor, Eloise Greenfield, Jerry Pinkney, Patricia and Fredrick McKissack, Walter Dean Myers, and another one of my heroes, a beautiful human being named Ashley Bryan.

To say I am honored is not enough. Saying I’m honored is, to paraphrase Samuel Clemens, similar to comparing the glow of a lightning bug to a bolt of lightning.

I am beyond thrilled.

And I think the best I can do is to recognize a very few of the many people responsible for my attendance here.

Starting with the jury members for 2024: Chair Emma K. McNamara, Dr. Pauletta Brown Bracy, Rose T. Dawson, Idella Washinton, and of course, Chrystal “Shady” Carr Jeter.

So much of life is a quest for belonging, a search for family, and I’ve been fortunate enough to have been a member of many encouraging families. Starting with the family of teachers who have guided, supported, and helped me. To my library family in Windsor, Ontario, including Angela and Janet Brown, Terry Fisher, Len Hayward, and Steve Salmons; to my Flint Public Library family, including Leslie Acevedo, Michael Madden, and Gloria Coles; to my publishing family at Scholastic, Andrea Davis Pinkney and Anamika Bhatnagar; and finally to my Penguin Random House folk, Andrew Smith, Melanie Chang, Adrienne Waintraub, the late Craig Virden, and most of all to my editor at Random House, Wendy Lamb, who pulled TWGTB [The Watsons Go to Birmingham—1963] from a slush pile.

So much of life is a quest for belonging, a search for family, and I’ve been fortunate enough to have been a member of many encouraging families. Starting with the family of teachers who have guided, supported, and helped me. To my library family in Windsor, Ontario, including Angela and Janet Brown, Terry Fisher, Len Hayward, and Steve Salmons; to my Flint Public Library family, including Leslie Acevedo, Michael Madden, and Gloria Coles; to my publishing family at Scholastic, Andrea Davis Pinkney and Anamika Bhatnagar; and finally to my Penguin Random House folk, Andrew Smith, Melanie Chang, Adrienne Waintraub, the late Craig Virden, and most of all to my editor at Random House, Wendy Lamb, who pulled TWGTB [The Watsons Go to Birmingham—1963] from a slush pile.

But, of course, the main reason I am able to stand here is because of two other outstanding individuals, H. E. Curtis and Leslie Jane Lewis Curtis, Mom and Dad.

I inherited many things from my father: my love of music, my sense of humor, my stubbornness. Also, my desire to always be there for my children, to give them what I could, and to love them.

Thank you so much, Dad.

But, as many of us are fortunate enough to know and appreciate, there’s something special about moms.

But, as many of us are fortunate enough to know and appreciate, there’s something special about moms.

And my mother was something else. I owe her so much. And not just because when I was born, on Mother’s Day, and my father wanted to name me after himself, Herman Elmer Curtis, Momma pumped the brakes with four words: “Like hell you will!”

Thank you, thank you, thank you, Momma!

She always had an encouraging word for the Curtii siblings, which is the accepted plural of Curtis, and she gave me the best review of my writing that I will ever get.

In fifth grade I was given an assignment to write an article as a reporter for an ancient Roman newspaper.

I brought a draft of my article home, worked on it, and gave it to Momma to read.

She looked at me and said, “I wish you hadn’t brought this home, your teacher is going to think an adult wrote it.”

Those words filled me with such inspiration and pride and lit a fire that was the birth of my career as a writer.

I tell my children that my mother was an old-school mom, which is a gentle way of saying if you acted up, she would knock your head off with anything that wasn’t nailed down.

I’ve dodged shoes, numerous grooming instruments, both sharp and blunt, and even plates full of food.

But now, at this late hour in life, I understand why every missile was launched. And I understand that every act of anger came from frustrations born of love.

And there was an ocean of love surrounding the Curtii.

And there was an ocean of love surrounding the Curtii.

My brother David, with whom I shared a bedroom, was four years younger than I.

I remember waking up one morning and going over to his crib to try to force him to wake up and play with me.

I climbed up on the crib and couldn’t believe what I saw.

David’s eyes were partially open and his head was half submerged in a pool of blood and vomit.

Memory is a powerful, sometimes kind thing; it sometimes shuts itself off, shielding us from events and scenes that are too difficult.

All I recall is running screaming from the room.

My next memory is of sitting around the coffee table with David’s unconscious body in Momma’s arms as my father tore through the screen door to borrow the neighbor’s car to take my brother to the hospital.

For some reason I found myself focusing on my mother’s beautiful, long, dark brown fingers.

I saw her hands were doing so much of the talking for her. It was as though I was witnessing and understanding the genesis of a new language, a language of hands.

I watched as Momma rocked David’s limp body back and forth, back and forth with her lips pressed to the crown of his head.

And how her fingers so tenderly kept closing David’s fluttering eyelids.

And how gracefully those fingers danced from David’s face to my little sister Cydney’s cheeks to brush away a stream of tears. And how they finally lighted on my forehead when I shut my eyes and used both of my hands to press Momma’s fingers into my face as tightly as I could. Knowing the strength of her fingers was the only thing stopping my head from exploding.

Momma whispered, “It’s alright, this is hard, but we’ll get through it.”

And we did. David lived another fifty years. And the dance of my mother’s hands will one day make it into a book.

And we did. David lived another fifty years. And the dance of my mother’s hands will one day make it into a book.

In June of 2012 I was scheduled to speak at Teachers College at Columbia University in NYC.

Three days before my appearance, twenty years to the day that my father had died, my mother passed away.

I knew the best thing for me was to go ahead with the speech. I made the talk a tribute to my mother.

Afterwards, as I was signing books, I noticed one woman at the end of the line letting everyone cut in front of her. She was obviously determined to be the last person I spoke to.

Huge red flag!

Finally, she was one person away.

I scanned the room for the security guard.

I gripped my BIC pen as if it were a knife and waited.

As I’ve pointed out too many times in this talk, I’m from Flint.

I’m not going down without a fight.

The woman extended her hand and said, “I liked your talk about your mother, and I have a question.”

Here we go!

She said, “Did your mother ever have anything to do with Michigan State University?”

I was surprised! I told her, “Why, yes! In fact, she was the first Black female student to live in the dorms.”

The woman sobbed and said, “My mother was your mother’s roommate at Michigan State.”

The woman sobbed and said, “My mother was your mother’s roommate at Michigan State.”

My mother had rarely but glowingly spoken about her roommate. But all I knew was that she was Jewish, and my mother was very fond of her.

The woman went on, “Your mother made such an impression on my mom. The way she handled all of the hate and attacks on her was…”

I interrupted, “What? The way she handled what attacks?”

The woman said, “She didn’t tell you? She had a horrible time there. One time this group…”

I stopped her mid-sentence.

This was the sort of thing that would bother me. I didn’t need the details.

But when I thought about the situation: first African American student living in the dormitories at a then rural college in Michigan in the late 1940s? Of course she had gone through hell. Of course she faced hatred and ignorance. Of course this must have been crushing. But my mother didn’t let it crush her.

The woman said, “Your mother is responsible for the way my mother raised me and my siblings. We’re all very progressive, social warriors.”

In other words, they are “woke.”

Years from now, historians will look back at these times and recognize what a twisted world we’re in when the word woke, a synonym for being aware and progressive and conscientious and caring, is considered a slur.

Then, through tears, the last person in line said, “My mother loved your mom so much she named my oldest sister Leslie.”

When I got back to the hotel that night, I called my sisters to see if Momma had ever said anything about MSU. But they had the same skimpy information I did.

When I told my sister Cydney about the woman at the signing, she told me that several months before she died, Momma had seen something on TV that said you could find anyone in the world through Google. She asked Cydney to go on that “internets thing” and see if she could find her former roommate.

Momma had the wrong last name and was unable to reach her friend. Obviously now I see she was looking to say thank you and goodbye.

It’s taken me a long time to figure out why Momma never shared the horrible incidents she endured at Michigan State with her children. But now I know.

It’s taken me a long time to figure out why Momma never shared the horrible incidents she endured at Michigan State with her children. But now I know.

Wisdom comes slowly, and it’s taken me all these years to appreciate the truth and beauty of the sacrifices my mother made to protect Lindsey, Cydney, David, Sarah, and me.

She took the bullet for Team Curtii.

She could have told her children the truth, which, even though she would have couched it in the least inflammatory terms possible, would risk stoking the fires of hatred in us.

And she didn’t want that.

She knew that as young African American children coming of age in the 1960s, there awaited an Arlington National Cemetery number of crosses for us to carry before and after we reached adulthood.

And she knew hatred is the heaviest and most destructive of all crosses to bear.

Hatred corrodes the vessel which carries it. And Leslie Jane Lewis Curtis was making certain her children didn’t go out that way.

At a signing a few years later, a librarian or a teacher handed me her book and said, “Your mother must have been a wonderful person.”

I know, I know, I should’ve said, “You’re right, she was.”

But I’m from Flint, my head doesn’t run that way some of the time.

I hadn’t mentioned my mother in that particular talk, and so I asked, “Why on earth would you say that?”

I hadn’t mentioned my mother in that particular talk, and so I asked, “Why on earth would you say that?”

She told me, “All of the female characters you write are compassionate, strong, and, most important, believable. And while I think you’re a good writer, I don’t think you could have come up with that on your own. I think you must’ve had a pretty good example.”

And she was right.

So, as I stand here before you on this beautiful Sunday morning, accepting this beautiful award, I say again, thank you, thank you, thank you, I am so honored and so proud.

And I gratefully accept on behalf of all of the Curtii. Those of the past, Herman Elmer Curtis and Leslie Jane Lewis Curtis; the Curtii of the present, me and my siblings; and those of the future, Ayaan, Ebyaan, and Libaan Curtis.

At least one of whom, if they so choose, will one day be standing up here, accepting their own CSK VHA LA.

Which is the sort of thing that doesn’t bother me at all.

Christopher Paul Curtis is the winner of the 2024 CSK–Virginia Hamilton Award. His acceptance speech was delivered at the annual conference of the American Library Association in San Diego on June 30, 2024. From the July/August 2024 issue of The Horn Book Magazine: Special Issue: ALA Awards. For more speeches, profiles, and articles, click the tag ALA 2024.

Single copies of this special issue are available for $15.00 including postage and may be ordered from:

Single copies of this special issue are available for $15.00 including postage and may be ordered from:

Horn Book Magazine Customer Service

hbmsubs@pcspublink.com

Full subscription information is here.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!