Amber McBride Talks with Roger

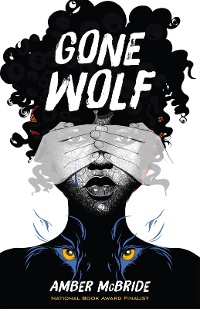

Spoiler alert: Gone Wolf, despite what you might surmise well through its first couple of hundred pages, is not set in a dystopia. At least not in the one you think. In her third novel, and first in prose, Amber McBride tells a story about a young, traumatized Black girl who, as Joan Didion’s famous aphorism has it, tells her own story in order to live.

Talks with Roger is a sponsored supplement to our free monthly e-newsletter, Notes from the Horn Book. To receive Notes, sign up here.

Sponsored by

Feiwel and Friends, an imprint of Macmillan Children’s Publishing Group

Spoiler alert: Gone Wolf, despite what you might surmise well through its first couple of hundred pages, is not set in a dystopia. At least not in the one you think. In her third novel, and first in prose, Amber McBride tells a story about a young, traumatized Black girl who, as Joan Didion’s famous aphorism has it, tells her own story in order to live.

Roger Sutton: When I first read your novel, I thought, Oh, it’s a dystopia, with this kid who has a guardian dog to help her. This is nice, but I know this kind of book. And it turned out it wasn’t that kind of book at all.

Amber McBride: That was the kind of vibe I was going for. I want people to think, Okay, this is interesting. We love dystopian novels. And then for there to be this twist about mental health and storytelling and how it can be healing. I love that that was your reaction.

Amber McBride: That was the kind of vibe I was going for. I want people to think, Okay, this is interesting. We love dystopian novels. And then for there to be this twist about mental health and storytelling and how it can be healing. I love that that was your reaction.

RS: It wasn’t like you changed your mind as you wrote the book, as to what kind of book you wanted to write?

AM: No, it was always going to come back to where it does. A lot of my books talk about clinical depression because I have it. I’ve had a lot of therapy, and I wanted to show how storytelling, or talk therapy, is so helpful to some people, especially young people. From the beginning, I knew that the narrative was going to change, and that people were going to think, Wait a second... With my editor Liz Szabla, we worked on how to balance each half: How much should be in the present day, and how much should we stick with the more dystopian vibe? I knew from the jump that Imogen was telling a story to cope with her reality. It was a story that she had told many therapists, but the therapist you meet, Dr. Lovingood, is the first one who says, “You know what, just tell me the whole story. I’m not going to tell you it’s wrong. Just say all of it.” And she gives Imogen space to work through her grief, which she has created a very fearful story around.

RS: It was so interesting to see her recounting to that doctor, in condensed form, a story I had just read. I started to see that story differently.

AM: That’s so good to hear, because there was that fear — to an extent, that I was telling the same story again, in excerpt form, a watered-down version of it. The hope was that because everyone who read the first part of the book would be privileged to the full story that when you heard it a second time, you’d be taking these nuances and seeing it in a different kind of way. That was what a lot of the editing came down to, honestly, getting the two parts to balance well. At one point I wondered if it was two books. It was really difficult to navigate making these two stories weave together in a way that felt authentic and not too difficult for middle-grade readers.

RS: And our perception of the threat in the story changes. Once we realize that Imogen is telling us a story she has imagined, we’re kind of relieved because this horrible dystopia hasn’t happened. At the same time, now we see this young girl in emotional trauma.

AM: Emotional trauma, but also it draws attention to the fear that a lot of Black kids, and Black people in general, still have: If we keep allowing certain histories to be retold a certain way, will we end up in the same place that we were before? In Florida, they’re teaching the “good” parts of slavery. To think of Black students in classes having to hear their teachers say that is mortifying to me. It also causes mental health issues for that child. Thank God Imogen is not in this situation, but oh my gosh, how are we going to reconcile our own histories and understand that the enslavement of Black people was the building of America? That is our history. We have to look it in the eye. It’s difficult for anybody to do. But if we ignore it, history repeats. We know that. I was looking at that fear. I wanted people to have that huge sigh of, Oh my gosh, she’s safe, to an extent. Her body is not in direct harm right now, but her fear was based on something. It’s one of those books that I think middle graders, young adult, and adults will all read differently. I wanted it to be accessible on all levels, because I think adults, and some young adults too, will read more deeply into what Imogen is saying, but middle graders might still get that gut feeling you had of oh, good, she’s safe. Maybe it will take until they’re a little older to say, “Oh my gosh, she was also afraid for real reasons.”

RS: You’re an English professor; maybe you can help me out here. Would you call this book, or at least the first part of the book, an example of Afrofuturism? Can you define that for me?

AM: Oh, this is an interesting question. When I read books by African Americans, I see African culture and folklore, and I still put that all into a folklore/storytelling aspect, whether it’s futuristic, modern, or set in the past. There is usually more world-building happening in Afrofuturism, whereas Gone Wolf relies a lot on the systems we already know. In Afrofuturism, I feel like I’m dealing with an entirely new world that I have to adjust myself to, where my book is building on tropes that are in our real world right now. But I don’t really believe in putting books in specific categories. I’m always mixing them and confusing people, and that’s what I like to do. If you look at books like Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye, that’s considered literary fiction. But it’s also a type of fairy tale. Is it magic realism? Is it historical fiction? It’s all these things. The books that mix those genres, I think, are best. If we were to categorize this book, I think I would call it a type of dystopian historical fiction, if that is a category.

RS: Well, it is now. It’s fun to play with expectations. I watched the finale of Hijack last night — it was really good. Idris Elba is on a plane, it’s been hijacked, and he’s got to figure out a way to take back control of the plane. We see him in big trouble at the very end, and we think: Idris is the star of the show. There’s no way he’s actually in trouble. But I like when a book or a movie or a television show does dare to shoot Idris Elba in the last scene, as it were.

AM: It’s surprising. It’s startling. I was young when I saw The Sixth Sense, and that did it to me. I have always loved that moment of, “I thought everything was happening one way, but it’s happening a completely different way.” I get that with a lot of Guillermo del Toro movies too — the villain is never who you think it is. I love that.

RS: To go back to Gone Wolf, one thing I thought was really neat was that the history of the story, if not the story itself, begins right now. It begins in about 2018, and what we’re seeing in the first part of the story is the result of real-life events that you and I and the world are going through. Scary Republicans and a scary virus.

AM: A very scary virus. Very scary political climate. Increase of hate crimes across the board. Antisemitism. All of that’s happening now. The rumblings of that were happening when I first started thinking about the concept for this book. I live in Charlottesville, Virginia, right now. My mother’s from Charlottesville. The Unite the Right rally happened here, resulting in a young woman named Heather Heyer being killed after a car was driven into a crowd. It was very dystopian that Charlottesville, which considers itself pretty liberal for the South, is where these people came to protest over a statue and caused so much turmoil. It made me think actively about what happens when we start not telling history. And then book banning increased. When I write a book, I follow my curiosity. The thing that’s nagging me at that time, which in 2017 was the rally, is the thing I write about. When I follow that intuition, my books are more timely, because I’m reacting to the world, the same way everybody else is.

AM: A very scary virus. Very scary political climate. Increase of hate crimes across the board. Antisemitism. All of that’s happening now. The rumblings of that were happening when I first started thinking about the concept for this book. I live in Charlottesville, Virginia, right now. My mother’s from Charlottesville. The Unite the Right rally happened here, resulting in a young woman named Heather Heyer being killed after a car was driven into a crowd. It was very dystopian that Charlottesville, which considers itself pretty liberal for the South, is where these people came to protest over a statue and caused so much turmoil. It made me think actively about what happens when we start not telling history. And then book banning increased. When I write a book, I follow my curiosity. The thing that’s nagging me at that time, which in 2017 was the rally, is the thing I write about. When I follow that intuition, my books are more timely, because I’m reacting to the world, the same way everybody else is.

RS: Wait, you were writing this book before we knew about COVID-19?

AM: I started writing the first ideas and drafts in 2017. There was a sickness in the story, but it wasn’t the COVID-19 virus or the pandemic. And then the book sat for a bit. It wasn’t fully developed. I had two other books come out. Then the virus happened, and it became so clear that that was another trauma we were all dealing with, so it was written into the book more profoundly than it was before. Also, I had lived experience that I did not have before, about what it would be like if some sort of virus arrived at our shores, and there was nothing we could do, and it affected the whole world. It shows that sometimes books have to sit until it’s time to write the most authentic version of them. It never felt completely right, which is why it hadn’t been published yet, and my other books came out first.

RS: Those were both verse novels, right?

AM: Yes. This is my first novel where the first half of the book is prose; there’s verse in the back end of the book. The word count is different: I think the highest word count on my verse novels is 21,000 words; this one is around 60,000 words. It was definitely a task. At one point, I didn’t know if this was going to be in verse or not. I had written it in prose, and it still wasn’t working, and I switched it completely into verse over a month-long period, and that still didn’t work. There was a lot of playing with format — getting all the pieces to work in this book was the most difficult thing. I think it was rewritten at least fifteen times to get everything to make sense.

RS: There are a lot of parts to it.

AM: There’s a lot happening. I’m really glad that my editor Liz saw my vision and helped get it to where it needed to be.

RS: What changed the most in the editorial process?

AM: When I was talking about the balance of the book, it felt like we needed more in the present day. I guess the fear when I was writing was that the first part is so interesting and intricate, and then we come to the real world, where it’s not simple, but we’re just in present-day Charlottesville, Virginia. Are people going to be interested in this story? Liz and I talked about what things we do around here, out in the country. We go apple-picking. There’s my local coffee shop, Baine’s Books and Coffee, where the book release is going to be. They have sticky buns — I love that coffee shop.

RS: And the church that Imogen goes to is a real church.

AM: It’s the church I was baptized in. The landmarks are real. There’s this duality: these horrible things happened in Charlottesville, and there’s a lot of complex emotions surrounding that, but I love this city. I wanted to highlight some of my favorite places, which became Imogen’s and her Big Sister Toni’s favorite places as well.

RS: Do you see yourself more as Toni or more as Imogen? Or are there pieces of you in both?

AM: Anybody who knows me will say I am one thousand percent Imogen. I’m very emotional and driven. Imogen talks about her feelings a lot, and it’s become an inside joke with my friends who have read the book. When I’m in any kind of debate with them, they’re like, “Listen, Amber, I feel like…” I cannot get away from it. My parents do it to me now. That was me when I was a kid: I wanted people to understand how I felt. But also, I see the world in a very artistic way. I am annoyingly a poet. I will describe a sunset really beautifully to a person just standing beside me. I need to stop, because it’s awful sometimes. I’m a daydreamer. I’m definitely Imogen. The dog, Ira, is based on my German shepherd, Shiloh, who passed away last year. She was thirteen. It was always me and Shiloh, so Imogen and Ira were like me and Shiloh. It’s a very mirrored comparison there. It was nice to have people read it and be like, “Toni is cool, and she’s hip, but you’re definitely Imogen.” Yeah, I know.

RS: Do you know the Shiloh books by Phyllis Reynolds Naylor? I think there are three—the first one, Shiloh, won the Newbery Medal. It’s a boy-and-his-dog story, and it’s fabulous.

AM: It’s an older book, right?

RS: Well, you would think so. Eighties.

AM: I have read it! There was a movie made afterwards, right?

RS: Yes.

AM: My Shiloh came from watching a documentary about a young girl who was born with her legs fused together. They called her Mermaid Girl, and she was just so joyful. Her name was Shiloh, so that’s who I named my dog after.

RS: You talked before about dealing with depression. I’m wondering how that intersects with you as a writer.

AM: I’ve been talking about depression a lot lately, because my last book, We Are All So Good at Smiling, was about clinical depression. I’m very open to talking about it, but I’ve never been asked how it affects me as a writer. For me, writing is a type of medicine. It’s why I write so quickly and have so many books going at once. I get to create the world and the circumstances, so it gives me this kind of autonomy in life that I crave. It also has often been my downfall. I can get manically obsessed with writing something when I’m in a depressive episode and not take care of myself, forget to eat, forget to sleep. I’ve written drafts of books in five days because of this. I think it makes me a good writer because I’m very in tune with what my characters are feeling. I also think it makes me extremely sensitive at all times, which is also difficult. But I’ve never not been able to write because I’m depressed. It usually is the one thing I can depend on. I should probably get some more hobbies. My therapist asks, “Amber, what did you do today?” And I’ll say, “I wrote three thousand words.” She’ll ask, “What else did you do?” I’m like, “Was there something else I was supposed to be doing?” I’m not antisocial, but I require a lot of alone time. I’m a very in-my-head human being. I use writing as a way to cope. The best thing I’ve learned is that everything I write doesn’t have to be published. I’ve got several books that won’t be published. They were written for me and my mental health, getting me through a difficult time. It is finding the balance between what am I giving to the world and what am I keeping for myself, for my own healing.

RS: Will those unpublished books make their way into other stories?

AM: I’m very protective of them. Maybe a name or concept, but often no. There are so many stories to tell. I come from this vastness perspective. I have to tell myself, “Okay, Amber, this is the story you need to write,” because there are a thousand I could write. If I have to shelve a book and keep it for myself, I often think that’s a gift I wrote for me, and I want to keep it very private. But I’m really thinking on this question a lot now. I’ve never connected my mental health and my writing.

RS: But you just wrote this whole book about a girl who’s dealing with her trauma by telling a story!

AM: Yeah. I need to bring this up in therapy now. My therapist will say, “I’ve been trying to tell you this for months!”

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!