An Excerpt from "I Am Myrtilla's Daughter" — The Zena Sutherland Lecture

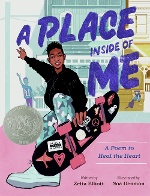

Like so many authors, I have had to deal with book banners, though on a relatively small scale. Last year my picture book A Place Inside of Me: A Poem to Heal the Heart was challenged in Virginia by a parent whose child thought it was about skateboards. Spoiler alert — it’s not.

My poem, written twenty years ago and beautifully illustrated by Noa Denmon (who won a Caldecott Honor for this book, her debut), shows the range of emotions experienced by a Black boy after the police-involved shooting of a girl in his community.

Like so many authors, I have had to deal with book banners, though on a relatively small scale. Last year my picture book A Place Inside of Me: A Poem to Heal the Heart was challenged in Virginia by a parent whose child thought it was about skateboards. Spoiler alert — it’s not.

Like so many authors, I have had to deal with book banners, though on a relatively small scale. Last year my picture book A Place Inside of Me: A Poem to Heal the Heart was challenged in Virginia by a parent whose child thought it was about skateboards. Spoiler alert — it’s not.

My poem, written twenty years ago and beautifully illustrated by Noa Denmon (who won a Caldecott Honor for this book, her debut), shows the range of emotions experienced by a Black boy after the police-involved shooting of a girl in his community.

When the school principal in Hanover County decided to keep our book on the shelves, a local elected official got involved, taking to social media to call our book “garbage” and implying that it was anti-police. The progressive members of the community responded by inviting me to be a special guest at their inaugural book festival; I traveled to Richmond, did a school visit, signed books at a Black-owned bookstore, and spoke to the press. One reporter from a Black newspaper asked to talk to me, but about twenty minutes into the phone interview he abruptly asked, “Why aren’t you famous?” My flustered response must have been inadequate because his piece never ran in the paper.

I begin with this anecdote because I would like us to consider the way fame and visibility shape systems of recognition. When I do school visits, students sometimes approach me to ask, “Are you famous?” And I always reply, “If I were famous, you wouldn’t have to ask.” It seems that kids aren’t entirely sure what fame is, but they know from an early age that it makes a person important.

I don’t generally have a problem writing in relative obscurity; I realized a long time ago that the kinds of stories I produce aren’t generally valued by “the market,” and part of “getting ahead” means “playing the game” which, to me, is clearly rigged. Fame was never a professional goal of mine — instead I aspired to what I have very nearly achieved: sovereignty and security. The commercial success of my Dragons in a Bag middle-grade fantasy series enables me to write what I want, when I want, how I want, without having to worry about sales.

During the pandemic I discovered a guilty pleasure on HBO Max. The Other Two is a comedy about Brooke and Cary Dubek, two adult siblings living in the shadow of their adolescent brother, ChaseDreams, who achieves sudden superstardom when his homemade music video goes viral. He’s given a record deal, but when it becomes clear that Chase can’t actually sing, his savvy, scheming publicist (played brilliantly by Wanda Sykes) finds other ways to capitalize on his popularity. Meanwhile, Cary’s acting career is stalled because he can’t even get an audition without having at least fifty thousand followers on social media. Brooke helps manage Chase’s career, overbooking him even when she can see that he’s unhappy. She ditches her “loser” boyfriend, Lance, only to watch him find mega-success as a designer of unwearable luxury sneakers. Their mother’s warm personality wins her a talk show, but Pat’s desire to please others leaves her exhausted and exploited by an entertainment industry that manipulates and monetizes everything.

The Other Two is a hilarious take on twenty-first-century celebrity culture and a sobering reminder that meritocracy is a myth. Chase’s lack of talent is no barrier to his continued success because he has a team of people working to ensure that he remains a highly visible, lucrative commodity. Brooke and Cary don’t want to live in their little brother’s shadow but can’t succeed in their own careers without buying into the very system they despise.

I don’t mean to suggest that all famous people lack talent; obviously, many artists are rightfully recognized for their brilliance. But a recent article in Poets & Writers Magazine, “Literary Prizes Under Scrutiny,” confirms what many writers of color already know. The article summarizes the findings of two studies conducted by Claire Grossman, Juliana Spahr, and Stephanie Young, poet researchers whose survey of U.S. literary prizes for adult fiction reveals that these awards are “increasingly powerful shaping mechanisms” that give select writers “attention…a wider readership and professional opportunities.” The number of literary prizes has increased exponentially since the start of the twentieth century (going from one prizewinner in 1918 up to eighty in 2020), yet it wasn’t until the 1990s that writers of color finally began to win wider recognition for their work. But, according to the article’s findings, the vast majority of those winners hold graduate degrees from MFA programs at elite schools, and since “literary production in the United States remains disproportionately white,” these prizes do not fundamentally change “a still-exclusionary literary landscape, offering only ‘a limited, curated version of diversity,’” according to the researchers.

Most writers never win an award for their work, and very few can earn a living by writing full-time. Despite the challenges I have faced, I consider myself fortunate; I am not famous, but I’m doing okay.

* * *

I grew up with the fraught legacy of the British Empire and harbor no imperialist ambitions myself. When I left Canada, I wanted nothing more than to become African American. As a child, teen, and young adult I consumed, studied, and adored British literature; Charles Dickens was my particular favorite, and I strove to write like him. I started grad school at NYU in 1995; when a friend from Detroit read a story of mine and declared that it sounded “soooo British,” I was mortified. I was just beginning to decolonize my imagination, a challenging process I described in my 2010 Horn Book essay (“Decolonizing the Imagination,” March/April 2010).

I eventually came to realize that hybridity for me would always be so much more than biraciality. I could not outrun or entirely reject my British heritage; my affection for some aspects of the culture imposed upon me and my ancestors did not nullify my rage, but I felt at ease only when I embraced the complexity of colonialism. Living in New York City helped, since many African and Caribbean immigrants from previously colonized countries were navigating the same choppy waters.

But it was here in Chicago that I finally became a U.S. citizen in 2021 after living in this country for almost thirty years. I am also a citizen of Canada and of St. Kitts and Nevis, where my father was born a subject of the King of England in 1941. He immigrated to Canada as a teenager but was not welcome in his stepmother’s home. My grandfather tried unsuccessfully to enlist my dad in the army, and then Aunt Ellen stepped in to save the day. She had been a member of the Pilgrim Holiness church in Nevis and so sought out the same denomination when she immigrated to Toronto. When her fifteen-year-old nephew needed a plan for his life, Ellen found a way for him to attend the affiliated Eastern Pilgrim High School and College in Allentown, Pennsylvania. She appealed to the congregation for help with housing, and a tiny Scottish woman, Nellie McKay, offered to host my father in her Toronto home when he wasn’t boarding at school in the U.S.

My maternal grandfather was minister of that Pilgrim Holiness church; it’s where my parents met, and when they married, Nellie became Grandma McKay, my Scottish granny. I don’t know where in Scotland she was born or when she left for Canada. I only know that she taught my mother how to make Yorkshire pudding; she had a son named Fred, who towered over her like a giant; and she knit cardigans for my brother, sister, and me. She attended my dad’s graduation in Allentown in 1966, and when Grandma McKay died, my father wept as if he had lost his mother. Again. I am named after his biological mother, Rosetta Elliott, who died in an asylum in Antigua a year before my father moved to Canada. I have no photograph of the original Zetta, only Aunt Ellen’s memory that my grandmother had “hair down her back.”

I learned early on how to live with shameful silences and unexplained absences. One strategy was to escape into a book where families were whole, happy, and complete. Another was to make up stories that filled the many uncomfortable gaps in my own reality. Thanks to my steady diet of British fiction, when I did dream of running away, I dreamed of England. I had the opportunity to study abroad while I was in college and jumped at the chance to visit England in 1991. Though I couldn’t afford to stay in Arundel for the whole academic year, I did manage to visit Wales and Scotland that fall.

The author's parents' wedding in Chatham, Ontario, 1967; Zetta and her older sister with their Scottish granny; and with a friend at Edinburgh Castle. Photos courtesy of Zetta Elliott.

I returned to the UK again and again over the years, sometimes as a tourist, sometimes as a scholar presenting at conferences, and more recently as an author conducting research for my books. In 2018, I began to think seriously about moving to Scotland after attending a publishing conference in Edinburgh. First Minister Nicola Sturgeon made a surprise appearance, and I marveled at the ease of this unexpected encounter with the Scottish leader. There were no metal detectors, no wands or pat-downs. Because there was no need. Scotland had one mass shooting, at Dunblane Primary school in 1996, and it never happened again — ever. As a progressive country led by a woman, Scotland was at the top of my “if I ever leave the U.S.” list. New Zealand was next for the same reasons. Today, of course, both women have resigned as leaders of their respective countries, but gun control is still in effect.

Then in August of 2022 I got an update from Ancestry.com. I had submitted my DNA to three genealogical sites and gotten disparate results, so I wasn’t surprised to see that they now claimed I was thirty-seven percent Scottish. A few years ago, they declared I was eleven percent Scandinavian, which is also impossible. My mother’s family is deeply invested in origin stories. They are stories — I have no proof that they’re true — but they shaped my understanding of my roots and my role in the world. I was always told that my mother’s father was of Irish stock; my uncles easily adopted Irish accents when impersonating their elders, though my grandfather, his parents, and his grandparents were all born in Canada, not Ireland.

It was easy for me to dismiss the sudden Scandinavian results, but I lingered over the Scottish ones. I checked 23andMe and sure enough, it declared that I shared the most DNA with folks from Glasgow. Intrigued, I reached out to a genealogist specializing in mixed Scottish and Irish heritage; she took a quick look at my family tree on Ancestry and immediately spotted a Scottish ancestor. My grandfather’s paternal grandmother, Isabella Stark, listed her mother’s birthplace as Scotland. I recently learned that my grandfather’s mother, Jenny Caldwell, was also of Scottish descent (the MacDougal clan, according to my uncle).

So last summer, I returned to Scotland for the third time to see if it still felt like a potential home. I met children’s literature scholar and author Breanna McDaniel for high tea at my hotel; Bre has made a sort of second home in Scotland, and I was eager to learn how my friend had forged connections and built community. After tea, Bre gave me a tour of the gentrified city center, renamed “Merchant City,” and she shared Glasgow’s long-buried involvement in the transatlantic slave trade.

The next day I signed up for a free walking tour, fully expecting that my older, White male tour guide would omit the historical facts Bre had disclosed. But to my surprise, the guide — let’s call him Bob — acknowledged the source of Glasgow’s wealth from the very beginning and pointed out repurposed mansions that once belonged to “tobacco lords” whose fortunes were built on the backs of enslaved Africans laboring in the Caribbean and North America. He revealed that Scotland was forced to align itself with England in 1707 because almost the entire nation invested in a failed scheme to colonize Panama. Bob also told us that some Glaswegian merchants were so wealthy that they paid to have sidewalks laid for their own private use, and doors were widened to allow servants to carry their masters inside on sedan chairs.

Near the end of the tour, Bob stopped in a lane called Virginia Court to tell us a heartbreaking story about an enslaved boy named Frederick who was given away by a tobacco merchant. Bob told us that merchants often offered incentives to get traders to buy loose tobacco leaves after all the bales had been sold — a pineapple, or a bottle of port. But one heartless Scot gave the child away instead. According to Bob — whose true passion was acting — Frederick managed to escape from his new enslaver, but no one knew what ultimately happened to the little boy.

A "wide blue door" in Virginia Court, Glasgow, Scotland. Photo courtesy of Zetta Elliott.

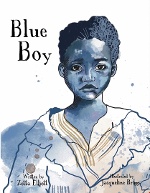

When the tour ended, I tipped the guide rather generously and went back to the hotel to write a glowing online review. For months in Chicago, I had been hearing two words in my mind: blue boy, blue boy, blue boy. He remained a mystery until I reached Glasgow last summer, took that tour, and heard Frederick’s sad story. I revisited Virginia Court on my own, took more photos, and tried to imagine what might have happened to that poor child. We know from our own contemporary standpoint what happens to vulnerable children who lack protectors. Earlier this year it was revealed that in the UK, asylum-seeking children were being abducted by human traffickers from hotels where they had been placed by the government. In the U.S., migrant children who crossed the border unaccompanied are working in dangerous conditions on construction sites, in factories, and slaughterhouses.

I kept asking myself why the merchant would simply give away a valuable young slave who could be exploited for the duration of his life. Was Frederick related to the trader — an illegitimate child, a likely product of rape? Perhaps it was simply inconvenient to have him around. Did my blue boy have a disability that made him less productive as a worker in the eyes of an enslaver? Did he contract an illness and weaken, leaving the merchant inclined to dispose of him? All the possibilities I came up with were disturbing and depressing.

Then, the day before I left Glasgow, I visited Kelvingrove Museum and saw a striking 1889 painting by Edward Atkinson Hornel. The Brownie of Blednoch depicted a ghoulish figure, and later that evening I pulled up the poem that inspired Hornel. Written in Scots by William Nicholson in 1825, “The Brownie of Blednoch” tells the tale of Aiken Drum, a creature with a frightening appearance — claws, no nose, glowing eyes — who only wishes to find a community to serve. He would do so indefinitely in exchange for a daily bowl of cream so long as they don’t offer him a new set of clothes. When one woman in the village breaks the rules, Aiken Drum departs, never to be seen again.

I immediately decided that my blue boy had to have an encounter with Hornel’s brownie. One challenge in writing about the past is representing traumatic events truthfully without terrifying or shaming young readers. I’ve found that a dose of magic is like the proverbial spoonful of sugar; having Frederick find a kind of liberation through his encounter with the mythical creature seemed like an ideal way to balance the horror of child trafficking.

The day after I returned to Chicago, I wrote these opening lines:

Behind a wide blue door lived a wee blue boy.

They called him Frederick.

Frederick was not his true name

and the grand house with the blue door was not his true home.

But no one in the blue boy’s world seemed bothered by the truth.

Within a few weeks I had written a satisfying tale about Frederick’s unhappy life with a tobacco merchant in Glasgow. When my blue boy is gifted to another trader, he winds up in a household where the servants go to bed every night without cleaning up the kitchen. Frederick sees the maid leaving a dish of cream on the back step; she explains that it is for a helpful brownie that serves their household.

Within a few weeks I had written a satisfying tale about Frederick’s unhappy life with a tobacco merchant in Glasgow. When my blue boy is gifted to another trader, he winds up in a household where the servants go to bed every night without cleaning up the kitchen. Frederick sees the maid leaving a dish of cream on the back step; she explains that it is for a helpful brownie that serves their household.

Undaunted by the brownie’s appearance, Frederick welcomes him inside and watches as he gets to work. The brownie explains that he left his last household after the farmer and his wife presented him with a set of fine clothes. Frederick timidly asks whether the clothes would also make him disappear. “There’s only one way to find out!” the brownie cries before leading Frederick into the glen and over to an old oak tree where he has stashed his fine clothes. Frederick puts them on and instantly disappears, and the brownie returns to the manor house alone.

* * *

I decided I would add an author’s note and a study guide to help readers further explore Scotland’s ties to slavery. There was just one problem. When I searched online for sources to support my tour guide’s story, nothing came up. I looked into Virginia Court and discovered that it was built in the early nineteenth century — but Glasgow’s tobacco heyday ended in the 1770s with the start of the Revolutionary War. Slavery was deemed inconsistent with Scottish law in 1778, and the transatlantic trade in slaves in the UK was abolished in 1807. So how likely was it that a tobacco trader would still have an enslaved child in the early nineteenth century?

I reached out to a historian with expertise in slavery in Scotland; now based in Wisconsin, Professor Simon Newman introduced me by email to Dr. Stephen Mullen, a professor at the University of Glasgow. Together they collaborated to produce a report for the university detailing the philanthropic donations made to the school over the centuries that could be linked to slavery. Dr. Mullen kindly shared his research with me, which revealed that there was a Caribbean boy named Frederick who was trafficked into Scotland in 1762 by none other than James Watt, famed Scottish inventor of a more efficient steam engine that was used widely during the Industrial Revolution. Watt had many jobs over his lifetime, and as a young man served as an agent in his father’s trading company, which did business in North America and the Caribbean. Apparently, the Watts were asked to procure a boy for Lady Spynie of Brodie House in the Highlands. Keeping an enslaved boy to serve as a page — an accessory, really — was the fashion in eighteenth-century Scotland. When the boy failed to arrive, the Brodies wrote to Watt and complained. Other correspondence discovered by Mullen revealed a description of the clothes Frederick had been wearing: breeches, a waistcoat, a black cravat, shoes, and a blue coat.

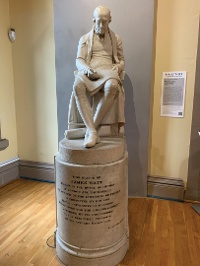

A statue of James Watt at the Hunterian Museum, University of Glasgow. Photo courtesy of Zetta Elliott.

It was clear to me that my actor/tour guide had taken more than a few liberties with the facts. There was no tobacco merchant who simply gave Frederick away on a whim in Virginia Court. Why Frederick never made it to the Brodies and what happened to him remain a mystery. I resolved to track Bob down when I returned to Glasgow in late October. I went back to George Square where the tours meet each morning but couldn’t see Bob anywhere. One of his colleagues directed me to the Riverside Museum, where Bob was performing in a Halloween show. He came out of a tent dressed like a vampire and listened patiently as I explained my project. There were a lot of things I could have said, but I kept my tone light and just asked if Bob would be willing to share his sources for the tale he told during our tour. I gave him my card and left the museum, not expecting to ever hear from Bob again.

To my surprise, Bob did send me an email the next day. There was no message, no apology — just a link to a newspaper article about historian Stephen Mullen’s research into James Watt. I don’t know if Bob is still conducting tours in Merchant City or if he felt at all ashamed after having his elaborate fabrication exposed. In my more generous moments, I think Bob’s heart was in the right place; perhaps he felt Frederick could be made a more sympathetic figure by adding a bit more drama to his story. I, too, am adding fantastic elements to reshape my blue boy’s narrative. Of course, the difference is that we don’t expect tour guides to lie to us. Do we? They tell jokes and stretch the truth but always with a wink and nod. Wanda Sykes’s character on The Other Two would argue that all publicity is good publicity. To my knowledge, there are no monuments to Frederick in Glasgow, though I saw at least three for James Watt. Only one, at the University of Glasgow’s Hunterian Museum, had a placard beside it acknowledging Watt’s ties to the slave trade.

If he was somehow separated from his traffickers, would Frederick know how — or whom — to ask for help in a strange land? Did his mother surrender her son willingly, hoping Frederick might have better opportunities abroad, or was he wrenched from her by force? If he spent the first few years of his life on a small island in the Caribbean, how would he find the long transatlantic journey and the bustling, overwhelmingly White city of Glasgow?

But most of all I wondered,“Frederick, why aren’t you famous?” What “powerful shaping mechanisms” operated to elevate the enslaver James Watt while entirely erasing the child he enslaved? What sort of team would we need to assemble to ensure that this Black child’s harrowing narrative, obscured for over 250 years, is never forgotten again? An agent or a publicist wouldn’t likely take an interest in a long-deceased child of whom there is no visual or written evidence that might easily be adapted and monetized into misery porn. Could a social media influencer make Frederick a household name (in Scotland, at the very least)? Or is it best to take a guerilla graffiti artist approach and “tag” every statue, portrait, textbook, institution, and website that even mentions Watt’s name?

The only upside of facing two decades of rejection in the children’s publishing industry is that I am generally prepared to self-publish everything I write. I reached out to Jacqueline Briggs, an illustrator based in Inverness, and commissioned a portrait of my blue boy. Jacqueline captured his sadness perfectly and agreed to do the remaining illustrations. We’re hoping to have the picture book finished sometime this summer.

This article is adapted from her 2023 Zena Sutherland Lecture, delivered in Chicago on May 5, 2023, and available on YouTube. From the November/December 2023 issue of The Horn Book Magazine.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!