Arthur A. Levine Talks with Roger

After twenty-three years as president and publisher at his eponymous imprint at Scholastic, Arthur A. Levine struck out on his own in 2019 to found Levine Querido, a small independent press devoted to finding and publishing diverse, underrepresented voices in literature for young people. We talk below about how that’s going.

Talks with Roger is a sponsored supplement to our free monthly e-newsletter, Notes from the Horn Book. To receive Notes, sign up here.

Sponsored by

Levine Querido

After twenty-three years as president and publisher at his eponymous imprint at Scholastic, Arthur A. Levine struck out on his own in 2019 to found Levine Querido, a small independent press devoted to finding and publishing diverse, underrepresented voices in literature for young people. We talk below about how that’s going.

Roger Sutton: I’m curious as to what kind of a reader you were as a child.

Arthur A. Levine: As is typical for young people who feel themselves to be outsiders, I was a voracious reader, because you don’t feel like an outsider when you’re inside someone else’s story. I read very early. Both my mom and my aunt were teachers, and they thought that I was showing signs of “reading readiness” when I was little. They taught me to read, and I was into it early, in kindergarten. I just continued to love books.

Arthur A. Levine: As is typical for young people who feel themselves to be outsiders, I was a voracious reader, because you don’t feel like an outsider when you’re inside someone else’s story. I read very early. Both my mom and my aunt were teachers, and they thought that I was showing signs of “reading readiness” when I was little. They taught me to read, and I was into it early, in kindergarten. I just continued to love books.

RS: What kind of books pulled you in?

AAL: That answer would depend on the age.

RS: Let's say ten.

AAL: At ten, my favorite book was The Mouse and His Child by Russell Hoban. I had two older brothers, so they would be constantly recommending books to me. Shortly thereafter I evolved into a particularly strong enthusiast for science fiction and fantasy. That’s what my oldest brother loved. I started reading Tolkien and Isaac Asimov and books like that. Ursula Le Guin, Robin McKinley.

RS: I’m curious about what gets people into our business. What got you here?

AAL: I had an answer when I first started answering that question, in the eighties, and I think it’s still the true answer. “Why did you go into children’s books?” I would say, “Well, when I thought about it, those were the books that meant the most to me, that had the most impact, the books I read and loved as a child.” When I was growing up I wrote poetry and I also really loved art. My mother is an artist, and she always turned to me for what I now would call art direction. I’d ask, “Where’s the light source?” And she’d say, “Oh, I should move this.” “Do you think it’s too busy over here, Mom?” When you think about it, what is the main place in publishing where poetry and art come together? That’s the picture book. Publishing in general, and children’s books in particular, involve the best parts of my personality. They make use of the things I really value as a person, in a way that not many jobs do.

RS: Give me an example.

AAL: Friendship is really important to me. Feeling close to people and sharing stories with them, talking with them on an intimate rather than a superficial level. And here is a job where I can do that with people all day. In fact, it’s demanded! I don’t think you can do the job well if you’re not emotionally available. Imagine if you were uncomfortable with that kind of interaction. It would be really hard to be an editor, because that’s what you’re encountering all the time — the feelings and childhoods and experiences of your authors and artists.

RS: And it takes so many people, on your side, to get any given book out the door.

AAL: That’s true. That brings up something I’ve also always been willing to do: to be vulnerable to the extent of telling people I love something and why. That’s how an editor spreads the enthusiasm about a book to the rest of the company, and then ultimately out into the world. It’s not a skill you pick up as an English major. It certainly is a skill you can learn, but it’s also a personality trait. I’ll tell you how I feel; I’m almost incapable of hiding how I feel. This is something that really helps if you’re going to be a publisher. I didn’t know that when I was choosing a job. Nobody ever talked to me about it. Nobody said, “If you want to go into that field, you should consider this question: how do you feel about standing up in a meeting with a group of people who you are not at all sure will share your opinion and just being out there, telling them how much you love something? Knowing that some people say, ‘Well, I didn’t love it.’ How will that feel to you? You can’t be deterred by that."

RS: As a publisher, distinct from an editor, I’m guessing you also have the occasion to crush certain editorial dreams of people who work for you. Is that true? You’re on the receiving end of those presentations, I guess, is my point.

AAL: Yes, well, Roger, here’s the great thing about being an independent publisher. It’s like back in ye olden days, when the questions that a publisher would ask their editors were: “Do you love this book? How much do you love it?” Because I’ve hired each of these people; and I trust their instincts and their taste. So I don’t have to crush their dream. If they think something is amazing, and I don’t see it, I trust that I will later. I really believe in that, and I think it works. Just this week, one of my editors sent me something — he said that he and his assistant had really liked it, but they weren’t sure. Should they ask the sales department what they thought? I said, “It sounds like you don’t really love it. That doesn’t sound like passion to me.” If you’re really passionate about it, then you don’t need to ask at this point. And if you’re not passionate about it, you shouldn’t do the book.

RS: I remember Elizabeth Law telling me that acquiring a book because you thought it would make money, even if you weren’t enthusiastic about it, never works.

AAL: Yeah, it really doesn’t. Who knows why that is? I could venture a guess. When you acquire something for that kind of cynical reason — “I think it sucks, but it’ll sell” — that is not the basis upon which you are going to spread enthusiasm. It’s hard enough to spread that enthusiasm when you are genuinely enthusiastic. Imagine how much harder it’s going to be if you really don’t think the book is that good, but you think it hits certain superficial checkpoints. People have said to me, “Well, what about Knopf publishing Fifty Shades of Grey?” I happen to know — I have a very good friend who’s in a senior position — that the editor who brought that to Sonny Mehta said, “You’re going to hate this book, but we love it, and we really, really want to do it.” And he said okay. It’s not the most literary book Knopf ever published, but it worked well for them.

RS: And I know people who love that series.

AAL: Yeah. That’s the thing. You have to feel, when you’re making those decisions, that if you love it enough, other people will love it. Your own love is the only non-moving target.

RS: Do you ever have to say no to something that you love? Aside from your children.

AAL: Not anymore. I have had the experience of being overruled and having that book go on to win a Caldecott medal. That is not a good feeling, let me tell you. But I no longer ever have to do that. There are definitely times when I will say, “Okay, you’re telling me you’re in an auction with twelve other publishers; we’re not going to win that, so let’s not bother.” Even if it sounds delicious and wonderful, it’s going to have to be somebody else’s delicious and wonderful.

RS: Do you feel like Levine Querido has a scope that would disallow certain books that you might personally want to publish, but don’t fit in with your mission? Or not?

AAL: Our mission leaves room for something that we call “best of its kind.” If something that is incredibly brilliant comes to us from a straight white person, say, then we can still publish it. That has to be extremely rare, because our mission is our mission. We have much, much more than we can possibly handle in terms of amazing stuff that we want to publish. More commonly, I’ll get pitched a book insert-very-mainstream-description written by a celebrity-of-some-sort-with-a-platform-of-X-million-followers. I won’t even read that. I’ll just turn it back and say, “Thank you very much for thinking of me, but that isn’t what we do.” That’s not something I love that I’m turning down, that’s something I’m not interested in. Our mission is what I’m interested in.

RS: How would you encapsulate your mission? What makes you different?

AAL: I don’t know if our mission makes us different, but we are looking for enormously talented authors and artists who will create books that give voice to previously underrepresented minorities, whether they are LGBTQIA, or people of color, Latinx, Indigenous writers, writers with disabilities, writers from minority religions. That is what we’re after, specifically. That isn’t a “flavor of the month” for us. That is what we do. And connected to that is our embrace of great writers and artists who are not American, who have published originally in another language. Because that’s another kind of diversity and human experience that Americans have had much too little of.

RS: I remember you telling me that one of your least favorite ways to see a review begin is along the lines of “Translated from the Norwegian…"

AAL: Even worse: “This Norwegian import…” Like we just put it on a boat and shipped it to the United States. We didn’t hire a translator and lovingly and painstakingly translate the book. That is an underestimation of a book, to just label it an import.

RS: I’m thinking about that book of yours that we just gave a starred review to…

RS: I’m thinking about that book of yours that we just gave a starred review to…

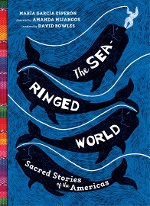

AAL: The Sea-Ringed World.

RS: You know that, barring something extraordinary happening, it’s not going to be a Harry Potter. But you don’t need a Harry Potter, am I right?

AAL: That is right. It would make my financial life easier, and that would be great. But finding a book like The Sea-Ringed World is a particular joy, especially since the process would have been much more difficult working from within a corporation, with a corporation’s usual procedures. I saw a piece of art from that book in the artist exhibit at the Bologna Book Fair. I took a picture of it, and I sent it back to Nick Thomas; senior editor and Meghan Maria McCullough; associate editor. I said, “I love this art. This art is amazing. Can you track it down and find out how we can see the whole book?” And they did, and we bought it. I didn’t have to first check if fourteen other people like it. Does it meet some kind of invented mathematical formula? To answer your underlying question: we have to make money to stay in business. I’m not running this as an incredibly wealthy industrialist who has endless amounts of money. We’re a small business that’s trying to be self-sufficient. But what we don’t have to do is apply the same expectations to every single book. It’s often very surprising which books come through and make you a lot more money than you paid originally, and which books fall short. Certainly when you’re working within a corporation, you’re often being asked to pay an exorbitant sum up front that actually requires — if you don’t sell two hundred thousand copies of that book, you are not going to make that investment. Here we don’t have to look at every book in that exact way. We can look at things the old-fashioned way, which is twenty percent of your books make up eighty percent of your income. That’s a really old formula, but it’s a nice formula, when you think about it.

RS: Does that work for you? I know you’ve only got a couple of years of data.

AAL: It seems to be working, yeah. I have confidence that it will. If you put out a list full of books you think are really, really great, some of them will catch fire right away. Maybe some of them will catch fire later. That happens — a book’s been out for a while, something happens, and it takes off.

RS: Well, I’m hoping it works for you. How low can you go on a print run, say, for a novel, these days? How few copies can you print of something?

AAL: I don’t have a bottom number. I think that generally, if somebody really loves a book, there’s no reason to assume it wouldn’t sell a reasonable number of copies, five thousand copies. There certainly could be a time when we would anticipate printing fewer; it’s hard to imagine, though. We’re finding that our sales are as strong, for each individual book on the list and the whole list, as they’ve been at any of the large publishers where we’ve worked. We don’t have to assume that we’ll only sell a small number of copies. A lot of our books have sold quite a lot better than they would have, just because they are not in competition with hundreds of other books on that particular list.

RS: Do you mean in competition with books on the same list, or books on the same topic on other lists? Math class is hard.

AAL: Let’s say you work for a large multinational corporation, and you are published on the Fall 2021 list. That corporation might have twenty-two imprints, each of which allows maybe twenty books. Or let’s say that all told, there are going to be four hundred books on the Fall 2021 list of Corporation X. No matter how you swing that, there’s going to be a group of books that get a lot of attention, a group of books that get a little attention, and a group of books that get no attention. And the latter two categories are going to be much more substantial. No matter who you are — how many people can you bring to ALA, for instance? Five? Ten? Think about how many people you’ve encountered at the various parties you’ve been invited to who are promoting their books. That’s the competition. You have to do your best to make sure your book and your author are the ones being promoted in that venue. So if you’re on a smaller list — our list has fifteen books, let’s say, Fall 2021, and six of those have authors and illustrators who live in far parts of the world, our translated authors, so you have nine books — you really are going to be able to pay attention to each one. You really are going to have a much higher percentage of people who get that kind of treatment. “Let’s put this person on a panel. Let’s get this person into this program.” You see what I mean?

RS: Because the stable is smaller, you can afford to give each of them more attention.

AAL: And I’m not in competition with anyone. When I go to Antonio [Gonzalez Cerna, marketing director] and say, “Let’s talk about the fall list,” he doesn’t nod and smile politely at me and then say, “Great to have this conversation; I’ll now talk to the twenty-one other heads of imprints, and then we’ll talk to the overall publisher, and then I’ll get back to you.” He says, “Well, this is what I think.” And together we come up with a plan. It’s just simpler. Of course we have much less money. The gestures that are really grand, an ad in the New York Times, those are things that we’re not going to be able to do. But we are going to be able to do a lot of things. And we’re going to have time to do a lot of the things that don’t necessarily cost a lot of money, but that cost time and attention. A publicist with fifty books on a list can’t devote the time to think about every possible bit of media interest for a particular book. They’re going to have their hands full just getting the books to award committees and review journals.

RS: I’m assuming that as your career has gone on, you’ve taken on more and more business responsibilities along with editorial, right?

AAL: When I started my own company I did have to take on a whole bunch of responsibilities that I never had before. Like I am the head of human resources. And there’s no contracts department — I am the contracts department. I’ve had someone say, “Can I just talk to your contracts person?” I’m like, “That’s who you’re talking to, sorry.” Again, because of our size and our finances, I’ve had to take on those roles. What I have now is authority that is the equal of my responsibility.

The first time I got to editor-in-chief, at Putnam in 1992, I had responsibility for the whole list and for other editors — my editorial authority was equal to that. What I didn’t have was authority over all the other decisions. I didn’t have the last word on production specs, what paper would be assigned to each book, what special effects might be used on the jacket. I would not have the last word on marketing priorities. I would be part of the loop — and I would even say I would be an important part of the loop — but not the last word.

When an author thinks of “my editor,” it’s the person who’s trying to shepherd their book through this process so that it will be the most beautiful, the most beloved, the most paid-attention-to, the most supported book it can possibly be. Really, no one wants to say to their authors, “Now it’s just the two of us, but once it gets beyond that, I’m just going to do my best to influence others. That’s all I can do, influence them, to make your book successful.”This goes back to the idea of people who are best at that part — being the ones who can be friendly and warm and politic and convincing and passionate in a way that doesn’t alienate others. But it isn’t authority. It’s influence.

RS: And that remains true. You could have a book that you did all the shepherding and cheerleading and anything you wanted, and since you’re the big boss, what you said went, and it could still not catch fire with readers, right?

AAL: Yeah. The end result is always up to readers. But at the end of the day, I can always say: “We did the best we could for your book, and we’ll keep doing the best we can for your book, even though it didn’t quite catch fire,” because I was the decision maker. If I thought your jacket would look better with foil, I would give you foil. That’s my decision to make. I’ll make two cents less — I’m making that number up — per book.

RS: Does everybody want foil?

AAL: No, that’s a random example. I think everybody wants their book to be gorgeous. Or even if they don’t, I want every book to be gorgeous. People want their book to be effective, whatever that means for the particular genre, the particular audience they’re reaching.

RS: I imagine one of the toughest parts of your or any publisher’s job is that in order to write a book, an author needs to have a healthy amount of ego.

AAL: Yes.

RS: But that, of course, can get in the way when it comes to the business of publishing that book. How do you negotiate keeping this person feeling valued but also making them realize that not only are there fifteen other books on the list, there are fifteen hundred other books competing with it on the very day theirs comes out?

AAL: First of all, my experience is that a very strong ego is actually very helpful in the process, because people with strong egos find it more natural to engage in a direct conversation with you.

RS: "Where's my FOIL?"

AAL: “Why am I not on that panel?” Even on a smaller, more intimate conversation about the manuscript itself, if people have a strong ego and are confident, then they will listen to your feedback as feedback. What Stephen Roxburgh taught me was the idea of the editor as the idealized reader — a person who is there for you, but is also just a typical reader. People with strong egos receive that well, and think, Okay, here’s feedback from a reader. If that person saw this or felt this, how do I feel about their reaction, and what do I want to do about it? When you have a person with a weaker ego, it’s sometimes harder, because they can be more defensive, and feel that they need to tell you why they did something, or just be adamant. At the end of the day, it’s always the author’s choice. You’re asking about easier or harder. I would choose somebody with a nice, strong, healthy, confident ego any day.

Sponsored by

Levine Querido

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!