A Journey of Transformation — The Zena Sutherland Lecture

My voice, like the voice of most everybody, is made of many different ways of saying things. I like to say things with my voice, and with my jaranita, but I also like to say things with images. I sometimes even like to say things with silence. This time I’m going to use my voice, some words, and some images.

"I like to say things with my voice, and with my jaranita."

A screenshot from Morales's presentation of the Zena Sutherland Lecture.

Image courtesy of Yuyi Morales.

My voice, like the voice of most everybody, is made of many different ways of saying things. I like to say things with my voice, and with my jaranita, but I also like to say things with images. I sometimes even like to say things with silence. This time I’m going to use my voice, some words, and some images. I hope that you accompany me patiently, because this is a moment when we gather together, just like the friends, like the collective, like the community, that we are.

I wanted to tell you a little bit about the journey of my voice through books and words and images. I was born in Mexico, as many of you know. When I grew up in Mexico, I always knew that I was an American because I was born on an American continent. When I arrived in the United States many years later, I was surprised to hear people call the United States “America.” For me, America has always been the whole continent. When I realized how the term was used in the United States, I started to resist it. I began calling the United States, “the United States.” It is easy to feel that someone is taking something away from you when they tell you that you are not an American because you were born in Mexico.

But later on, I also learned that America is a name that was given to the continent after the Europeans came and conquered it. Words have power, and their use helps give names to the vision that we have of the place where we live. I decided to adopt a new term — it’s not something that I have come up with; it’s something that I have learned from other people. I know now that I come from a place called the Abya Yala, a name from the Indigenous Guna language. It means “land in its full maturity.” This name was adopted for the American continent at the Summit of Indigenous Peoples and Nations of Abya Yala (Quito, 2004). It is new for me, but I’m starting to get accustomed to using words to name a new reality.

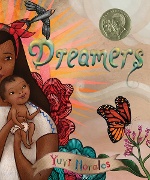

Some of you might have already seen part of my story about my journey through books in Dreamers. I was someone who loved to draw since I was a little kid. Those drawings that you see in Dreamers are actually my drawings that I made, sometimes next to my mother’s sewing machine; she would bring me paper and pencil so that I would not get bored while she was working. When I was growing up in Mexico, I didn’t have books. What we had were magazines, comic books. I admired them so much. They were my literature. I admired the artwork, which wasn’t necessarily for children, but showed me that if you were an artist, you could create things like what I saw on those pages. I still have a very deep connection with comic books because they were part of my childhood. Eventually, when I was in middle school, this book came to me: La increíble y triste historia de la cándida Eréndira y de su abuela desalmada by Gabriel García Márquez. This book opened up an image of myself as someone who was a reader, which I didn’t have before. Just like in Dreamers.

Some of you might have already seen part of my story about my journey through books in Dreamers. I was someone who loved to draw since I was a little kid. Those drawings that you see in Dreamers are actually my drawings that I made, sometimes next to my mother’s sewing machine; she would bring me paper and pencil so that I would not get bored while she was working. When I was growing up in Mexico, I didn’t have books. What we had were magazines, comic books. I admired them so much. They were my literature. I admired the artwork, which wasn’t necessarily for children, but showed me that if you were an artist, you could create things like what I saw on those pages. I still have a very deep connection with comic books because they were part of my childhood. Eventually, when I was in middle school, this book came to me: La increíble y triste historia de la cándida Eréndira y de su abuela desalmada by Gabriel García Márquez. This book opened up an image of myself as someone who was a reader, which I didn’t have before. Just like in Dreamers.

* * *

One day, I put things into a backpack, and with my child and my soon-to-be husband crossed a bridge and arrived in what would become my new home, the United States. There, as an immigrant, I experienced the things that many immigrants experience, which, especially if you don’t know the language, might be confusion, might be sadness, might be loneliness.

Until one day I arrived in a place that I had never seen before. There, a new world opened up to me. At the library, my first surprise was that there was a body of work, beautiful work, made especially for children. My second surprise was that not many, but some, of these books were made by and for people like me. They were made by people who were my same skin color. Perhaps they spoke Spanish, or they were immigrants like me. There were only a few of those books. I started learning how to make books because I wanted to tell stories. The biggest of the gifts that the library gave me was a realization that we all have things to say, that we all have stories, and that we all have different ways — our voices take different forms — so we can tell those stories. And the stories that we carry with us, they are all connected.

To me that was like fire in my heart. How joyful, how moving, how inspiring, to realize that there is not one single story, that there is a universe of stories. Some of those stories were at the library. Some of those stories were inside of me, too. And they were inside of everybody, actually — all the people that are here, all the people that inhabit this world. We all have stories.

At some point almost twenty-two years ago, I started unlocking those narratives that I had with me, those that I had brought from Mexico, where I was born, where I grew up, and some of the narratives that were weaving with the stories and experiences I was living as an immigrant in the United States. I began trying to tell those stories in the format of the books I saw in libraries.

I realized also that I was making books part of my life, so now I think that perhaps I am someone who carries books. I carry books in my heart, in my hands, as I am making them. I carry them when I read them to children, or when I share them, or when I bring them as gifts. I am a book bearer, and so are you. You are, whether you create them, or you read them, or you carry them with you, or you share them, or you live and love books. Eres un cargador o una cargadora de libros. Book bearers are those of us who see books as a way to learn and unlearn how to inhabit this world. And there are many of us. Most of the time, luckily, we find one another. We find one another in the street, at conferences, in libraries.

And we have our work. We are making something that we love. But when I started making books, I realized that the reasons and the stories that I was unlocking have been changing. Nowadays I question myself a lot: why and how and when and what and who are the characters and the stories that I’m portraying? What are those stories going to do to take me into a journey of understanding, and to transform our world? This quote from Shaobo Xie’s Voices of the Other essay always pulls me: “If children’s literature and the criticism of children’s literature take upon themselves to decolonize the world, they will prove the most effective postcolonial project in the long run, for the world always ultimately belongs to children.” The books that are on the shelf, that you are going to read to your child tonight, were created for una infancia, for a niño or niña or niñe. The children in the United States, the children of the whole American continent, are our children, the children of our world. In Mexico, we do have a colonizing history. While the United States doesn’t have a colonizing history, there is a settlers’ history, and that is part of our reality. It is part of how we approach our stories and how we approach our work.

* * *

I’ve been making books for children for a long time, and I would think that maybe now it would be getting easier. I’m sorry to tell you that it’s not.

One of the things that books have given me is a lot of questions, and I take that as a gift. I am grateful for the questions that my work brings me. Like my friend Lía García “La Novia Sirena” says: “Pero qué bonito es dudar de una misma — but how beautiful it is to doubt oneself.” Because doubting opens the door for us to go out and search, to be researchers, to find those things that we don’t know. When we doubt, then finally we move, and we go out, and we look.

My books are always propelled by questions. But as I grow older, my questions are becoming harder to answer. I’ve been making books alone for a long time. Not truly alone, but in a way where I envision myself as all alone at my desk. That’s a very simple way to make books. But what happens when we open up, when we start our journey of making books and we are not alone? When we look and look for the things that we cannot see?

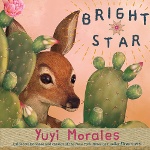

My latest book is Bright Star in English, Lucero en español. Because I was making a book about the borderlands, the place where Mexico and the United States meet, I decided to go there and start researching and investigating, and also talking to people. I learned things I didn’t know. I realized that the borderlands are a place where life thrives, even though we might not see it.

My latest book is Bright Star in English, Lucero en español. Because I was making a book about the borderlands, the place where Mexico and the United States meet, I decided to go there and start researching and investigating, and also talking to people. I learned things I didn’t know. I realized that the borderlands are a place where life thrives, even though we might not see it.

Where there might be water. Where also there might be fences and walls. Those fences and walls, yes, they are put in place to stop people from attempting to cross into the United States. Usually they don’t stop anybody. What they do stop are animals and plants. They destroy our environment. They don’t stop people, but they push people to look for places where they can cross that are usually even more dangerous.

In order to make this book, I was finally able to put a story together. A story of life, of animals, of people, of plants, who are in our hearts because it’s the planet where we live, and it is the planet that lights our hearts. It is our home. But, well, this place is not always being taken care of in the way that it should. Especially for those younger creatures, including humans, animals — everything alive can be in danger of having to stop their journey of looking for the things that they need to survive.

Of course, I couldn’t make this book alone. And I was trying to learn new ways of making my books. Something that I am unlearning and learning again is how can I connect to the stories that are around me so that I can tell stories that will help me transform, and will help us all transform this work. What I know now is that we can never do it by ourselves. We always have to go and connect with other people.

One of the people I talked to is my friend Sergio Avila. Sergio took me through the Sonoran Desert; he’s an expert of the desert. He showed me many things, and as he was taking me to a place by the river, I was asking questions again. The question that I had for making the book Bright Star was: When something really, really hurtful happens to you, when something irreparable happens to you, how do you heal? How do you repair that? If something happens to a child, how can we ever expect that child to be able to restore themself, and be wholesome and happy and productive again? Sergio said, “Yuyi, I’m going to tell you something. You are never going to find the answer for your question. Because there is no one answer for that question. The answer is that we go on. The answer is that we sit here and we talk. The answer is that we get up eventually, and we go on, and we eat, and we go to the bathroom, and we sleep, and we go to school, and we go to work, and we continue living. Through our living and through our going and our journeys, we continue finding different actions that bring the answers to questions.”

How stirring to realize that there is no one single solution or answer. There is a universe of answers. Questions are something very valuable, especially when we are book bearers, when we are making, sharing, and living books. So what questions can we ask ourselves about our work, if we are working with children, if we are working with books? Here are some that I’m still asking myself.

* * *

Are we making books that support the idea that the world is made for those, and only for those, who can generate wealth? Sometimes questions are hard, because we have to look really deep inside. We might have to see something that we adore, which is our work and our stories, and have to look at them with a different eye, with a critical eye, and question ourselves.

For characters in the stories that we are writing or sharing: are we asking them to model how to actually do better? Or to be deserving or obedient in order to experience a successful outcome?

Are we making books that value intelligence and “civilized” behavior? Maybe we didn’t think about it before. I know I didn’t think that when I was asking, in a book, for a child to be intelligent that I was asking them to transform into my idea of intelligence or of civilized behavior.

Do our stories suggest that people are of more value if they work “harder”? That has been a part of my philosophy of life, showing myself and the world, especially people like us who are immigrants, that we are hard workers. We will not even take care of ourselves because we are giving everything to be seen as people of value.

Do our stories champion the idea of doing things bigger, faster, quicker, “better” than others, and other forms of competition?

Are we creating books that reproduce beliefs and prejudice inherited from a violent culture?

Do our books reinforce the idea that punishment brings learning?

Does our work advocate only for a particular individual’s well-being? Only for those who are close to us, our family, those who we love, those who look like us, those who think like us?

Does our work support the idea that adults know better than children? That’s a hard one, because, with good intentions, sometimes, we might not realize that our stories and what we express in our work might be telling children that we have the answers, that we know better than them, that they should grow and be more like us, and that we are expecting them to be more like us. We have to be careful with that.

Does our work promote the idea of “normal”? That there is one way of being normal, and everything else is something that is not valued, is something that is at the edge or even outside the edge?

With the privilege that we have — because I’m a published author, because you might be a bookseller, a publisher, an educator, a book promotor, or simply because we are adults — let’s ask ourselves: how can we support and open the space for the voices that are usually ignored?

As feminist Brigitte Vasallo says: “Let’s start building something different.” How can we start building something different with our work?

We are going to have to learn from one another. Over the last few years, I’ve valued how rich is the learning that I get from other people. From collectives, from communities, and also from other women. I’ve been learning to create community, something that I have never done well before. I’ve been amazed by the results from these collectives, from learning from other people, and working with other people. Well, now I’m excited to realize that there is not one single voice; that there is a universe of voices.

"I've valued how rich is the learning that I get from other people...I've been learning to create community."

Image courtesy of Yuyi Morales.

If we could hear the many, many voices out there that sometimes we ignore, if we could bring them into our work, how could we deconstruct that work and then create something different? I’m going to offer you some ideas, and I would love you to offer me some, too.

* * *

We can begin asking questions from genuine curiosity. It would be so exciting to know something about all of you that I didn’t know before.

We can start making things that make us happy even if they don’t turn out right, so that we don’t do only those things that we are going to be successful at, that we are going to be good at, but that we do the things we love.

We can read and know stories different from the ones we have always heard.

We can also listen to those complaints about us that make us feel uncomfortable. That is hard. And examine how they are related to our actions. This is also very difficult, especially if you are an author. Our work is out there. Our work is public. A lot of people will read it. There are going to be a lot of responses, and some of them are hard to hear. But I wonder what will happen if we could listen to the criticism or the complaints, and we could use them to grow. I know it is not easy, and if you have some experience with that and some advice for all of us, I would love to hear it. I’m still learning.

And what about nurturing connections with people with whom we can make mistakes, so that they hold the space for us for learning and for reparations? Getting together with other people who we can grow up with is one of the most beautiful things that can happen.

Also breaking binary thinking and embracing plurality instead, so that our choices and our possibilities are infinite. There is not just good and bad. There is not just black and white. And there is not just she or he. But there is a universe of possibilities, because we are the universe of possibilities, and the more we reflect that plurality, the more we are reflecting the real world.

What about building community and spreading radical trust? That is also a hard one, to trust someone you don’t know and to give and receive trust to someone you just met. But if we can have that agreement that we can love and respect anybody just as much as we love and respect those who we have known for a long time, if we could give that to anybody around us, we would be practicing radical trust, and I think that our community will flourish.

Finding or creating celebratory words or new words to name things that are not part of the norm. The use of inclusive nonbinary language is difficult in the English language. It is even more difficult in the Spanish language. I have encountered resistance to the use of inclusive language. A lot of people are going to say: “Why are we going to change something that we have always used? Why can’t you respect the fact that I don’t want to name the difference? I don’t want to name those who have always been invisible to me. I want to keep seeing just two sides of everything.” It is not easy, especially when you have had so many years, like me, speaking in a language that is not inclusive. I now practice it every day, trying to remember and use inclusive language, especialmente en español. I hope that you are all patient with me, but also that you hold me accountable when I forget, so I can continue growing.

Something else that we can do is break mandates, roles, hierarchies, and practice horizontal connections, so that we are all in the same constellation, and we are all shining together. And yes, remembering and celebrating that we are always in process.

So does that mean that we are going to have to revolutionize ourselves, too? Not only our work, but that we have to change the way that we live, the way that we wake up every day, the way that we speak, the way that we make our stories?

I will say yes. Yes, yes, yes, and I’m glad that we have this opportunity in this lifetime to make changes, to live lives different from the ones that were given to us, lives that we can build, that we can choose.

So here are some words to help book bearers imagine, name, and revolutionize our vision of the world. These words are not mine. These are the words of other book bearers, and I want to offer them to you.

- E. Sybil Durand and Marilisa Jiménez-García: “We — scholars and teachers of youth literature — also need more books that can serve as windows for youth of color to envision their identities and experiences in nurturing, restorative ways. We need celebratory narratives that acknowledge a colonial history but view it as a source of strength that can help readers imagine new possibilities for a diverse society.”

- Sonia Nieto: “Passively accepting the status quo of any culture…[or] simply substituting one myth for another contradicts its basic assumptions because no group is inherently superior or more heroic than any other.”

- Sandra Xinico Batz: “Nationalism seeks to homogenize differences to position the so-called civilized, the intelligent, those who work harder, the ones more capable to create riches, while everyone else will support the structure.”

- Aura Cumes: “Violence has been invented to kill those whose humanity is put in doubt.”

- Debbie Reese: “Story ideas sound good. But writers and editors absolutely must stop and think about readers.”

- Patricia Enciso: “Please consider the values and challenges of writing and reading those stories that seriously engage with deep cultural differences — not as adornment or foil — but as the story we have longed to read about our place in the American hopescape. I will say the United States hopescape — or the American, because then we include everybody in the continent.”

- Edi Campbell: “We need workers who honor the past while creating a new future. I’d say forget patience, we’ve been patient too long. Look back and fly forward.”

- Somaiya Daud: “If you think your platform or voice or space is big enough that it can make a difference, then it is absolutely necessary to consider turning it over, however temporarily, to someone from the community you want to speak for.”

- Daniel José Older: “When we fight for diverse books we’re really just fighting for a more honest literature. Books that tell the truth. Because when we say, ‘We Need Diverse Books,’ we’re really saying, ‘We Need Books That Don’t Lie to Us About Who We Are or Whether We Exist.’”

And so we create, and we will be creating. Let’s create something together.

Let’s create a safe space where children can recognize the wonders of one another, and where they can imagine, propose, and contribute to building joyful ways of inhabiting this world, surprising ways of inhabiting this world, dignified ways of inhabiting this world, caring ways of inhabiting this world. And I would love to hear a word that you can insert here, so that when we create, and we create our books, and we create a space where children can read these books, we are making a safe space for them to be exactly who they are, not to ask them to be something different, but a place where they are safe, where they are fed, where they are cared for, where they are respected, where they are loved, and they can finally have the opportunity to be the protagonists of their own stories and decide how they are going to create the world where they want to live.

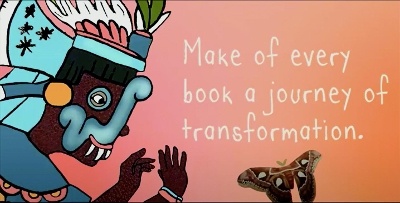

So after all these years of making books, are things easier now? Well, not for me. I like this quote by Joy Harjo: “If it is going too easy, you might wonder, ‘am I going deep enough?’” I will say, if we want to go deep enough, it is worth making of every book, whether you share it, read it, love it, make it, draw it, write it — make of every book a journey of transformation.

Image from Yuyi Morales's 2022 Zena Sutherland Lecture. Image courtesy of Yuyi Morales.

Because how exciting and stirring to realize that there is a universe of books, and that for every book that has won awards, for every book that has made it onto the shelves of the public library, or the bookstore, or your school, there are many, many books that are supporting those stories. The true richness happens in the many books that are being created and shared right now.

I want to finish this by offering you the possibility of us creating together, creating art to heal, books to grow, and stories to transform.

This article is adapted from her 2022 Zena Sutherland Lecture, delivered virtually on May 6, 2022. From the September/October 2022 issue of The Horn Book Magazine.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!