A Publisher's Perspective: Modern-Day Merits of Diverse Books

During the film adaptation of Wicked, the Wizard says, “The best way to bring folks together is to give them a real good enemy.” The terms “diversity” and “DEI” (diversity, equity, and inclusion) have been recently miscast in that role, to mean unskilled people, unfairly hired or otherwise prioritized, and any topics or ideas outside of the very most mainstream. In reality, that couldn’t be further from the truth. Despite a political scheme that falsely claims DEI is the root cause of everything wrong with this country, let me tell you a different story — a true story of how diverse books have helped our society come closer to a better version of itself.

During the film adaptation of Wicked, the Wizard says, “The best way to bring folks together is to give them a real good enemy.” The terms “diversity” and “DEI” (diversity, equity, and inclusion) have been recently miscast in that role, to mean unskilled people, unfairly hired or otherwise prioritized, and any topics or ideas outside of the very most mainstream. In reality, that couldn’t be further from the truth. Despite a political scheme that falsely claims DEI is the root cause of everything wrong with this country, let me tell you a different story — a true story of how diverse books have helped our society come closer to a better version of itself.

When Lee & Low Books was founded in 1991, what was considered “diverse books” for children was a small niche. How small? According to the Cooperative Children’s Book Center (CCBC), diverse books comprised less than ten percent of new children’s books published each year — a number that remained virtually unchanged from 1994 to 2013. (Note that between 1985 and 1993, the CCBC was documenting “books by and about Black people only”; it has since expanded its analysis.)

The prevailing assumption at the time was that there wasn’t a market for diverse books because White readers would not buy books about those from different backgrounds. The belief went on to say that since minority populations were individually smaller, and since they were thought to be the only ones who would buy books that reflected their cultures, the audience and demand for those books was not worth pursuing. That meant literary agents were not looking for diverse work because publishers were not looking, etc.

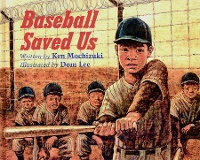

Our theory was that if we wanted to see more diverse books in print, and we put those books out into the world, an untapped market would emerge to purchase them. We got to work. In 1993, we released our first list, including Baseball Saved Us by Ken Mochizuki, illustrated by Dom Lee, about a boy and his family in a Japanese incarceration camp during World War II. It helped expand the parameters of what stories could be told in a picture book — and put us on the map. Librarians, who were our earliest supporters, noticed immediately. Many school librarians had noted a pronounced lack of representation in children’s books, and Lee & Low’s offerings filled a conspicuous void.

Our theory was that if we wanted to see more diverse books in print, and we put those books out into the world, an untapped market would emerge to purchase them. We got to work. In 1993, we released our first list, including Baseball Saved Us by Ken Mochizuki, illustrated by Dom Lee, about a boy and his family in a Japanese incarceration camp during World War II. It helped expand the parameters of what stories could be told in a picture book — and put us on the map. Librarians, who were our earliest supporters, noticed immediately. Many school librarians had noted a pronounced lack of representation in children’s books, and Lee & Low’s offerings filled a conspicuous void.

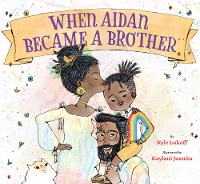

In 2000, we launched the New Voices Award to attract unpublished authors of color. The main reason behind the contest was that we noticed that a small, select few BIPOC authors and illustrators were being published again and again by the big houses, so we surmised that the industry was long overdue for an expansion in the BIPOC creator ranks. From there, our focus naturally expanded to include other marginalized groups, such as those with mental and/or physical disabilities and those within the LGBTQ+ community. Our definition of diversity was not set in stone and could expand to include people from other groups who experienced similar biases and needed their stories heard. When we published When Aidan Became a Brother by Kyle Lukoff, illustrated by Kaylani Juanita, in 2019, for example, the book received four starred reviews and numerous accolades. When Aidan Became a Brother not only showed that a landmark picture book featuring a trans protagonist could become an award-winning strong seller, it also proved the need for more stories like this. In the mid-2000s we released a viral social media campaign called the Diversity Gap Studies to shine a light on media outside books (e.g., film, television, and theater) that revealed a lack of representation in their ranks tantamount to book publishing’s disparity — which implied a systemic problem.

In 2000, we launched the New Voices Award to attract unpublished authors of color. The main reason behind the contest was that we noticed that a small, select few BIPOC authors and illustrators were being published again and again by the big houses, so we surmised that the industry was long overdue for an expansion in the BIPOC creator ranks. From there, our focus naturally expanded to include other marginalized groups, such as those with mental and/or physical disabilities and those within the LGBTQ+ community. Our definition of diversity was not set in stone and could expand to include people from other groups who experienced similar biases and needed their stories heard. When we published When Aidan Became a Brother by Kyle Lukoff, illustrated by Kaylani Juanita, in 2019, for example, the book received four starred reviews and numerous accolades. When Aidan Became a Brother not only showed that a landmark picture book featuring a trans protagonist could become an award-winning strong seller, it also proved the need for more stories like this. In the mid-2000s we released a viral social media campaign called the Diversity Gap Studies to shine a light on media outside books (e.g., film, television, and theater) that revealed a lack of representation in their ranks tantamount to book publishing’s disparity — which implied a systemic problem.

In 2014, We Need Diverse Books (WNDB) was launched from a Twitter hashtag, and it is now a national nonprofit. The work that WNDB does to advocate for its namesake helped push the idea that diverse books for children are not a niche market but rather a mainstream one. The following year, Lee & Low launched a demographic survey called the Diversity Baseline Survey (DBS), which has had three iterations, each four years apart. The 2023 statistics showed the industry at 72.5% White, down from 79% in 2015, clearly showing the field was gradually becoming more diverse.

Diverse hiring benefits individual companies and entire industries. Those businesses that choose to embrace this practice are able to leverage the experiences, knowledge, and perspectives of a broad workforce and are made stronger for it. Publishing, like many industries, suffered from a distinct lack of representation in its ranks. If the industry were to remain relevant, it needed to welcome different people to sit at the table. There was also the notion that if the diverse books themselves were to have a chance at becoming a bigger part of the industry, it would need staffs that reflected the growing diversity in children’s books. This connection may have provided the tipping point in our seeing more diverse books come to fruition. When George Floyd was murdered by police in 2020, the world protested — and the demand for diverse books rose sharply. In 2024, the CCBC reported that the number of diverse children’s books published per year made up 51% of the new books published.

Commercially, publishing has simply reacted to and provided for a pronounced demographic shift. The 2012 U.S. Census projected that by 2020, those under the age of eighteen would consist of a minority majority for the first time. This transformation of the population is not a surprise since diversity is baked into “the American experiment,” and to deny this is to violate the natural social evolution of our nation. As a publisher, as a country, we had surpassed parity, but there were many who wanted to go back — and they are currently louder than ever.

When diverse books eclipsed parity, it symbolized two things. One: there was a demand. Two: they were a threat. When they became popular and numerous, the mass challenges ensued. For those who want to turn the clock back, their objectives are clear: they have decided for us that we will not be allowed to progress as a society through honest storytelling and free speech, and that includes the books our children are permitted to read. Books are being banned not necessarily because parents are sincerely concerned about what their children are reading but rather because the powers that be are afraid: afraid that children will be taught truthful history based on well-researched, verifiable facts; afraid that this knowledge will lead children to ask the right questions, and when they grow up and assume the role of tomorrow’s leaders, that they will want for a better world.

* * *

While diverse representation is likely to lose some ground in the near term, this is the perfect time to reflect on the positive contributions that diverse children’s books bring to readers and our society.

Compassion and empathy are key touchstones in many diverse books themselves and in the movement to promote them. Rudine Sims Bishop’s mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors approach to children’s books highlights how books can provide an entry point for readers to see themselves and to imagine what it is like to be those different from themselves, while being able to step over the transom and walk around in other people’s shoes. This can help to dismantle stereotypes and break down barriers not only within children’s stories but also in real life.

Kindness and respect may feel like they’re in short supply nowadays, but diverse books have never lacked for generous amounts of both: kindness for those different from oneself; respect for beliefs or cultural traditions unfamiliar or different from one’s own. From the hundreds of stories we have published, we have found that the prevailing thread in diverse storytelling is that our commonalities far outweigh our differences.

Inclusivity and equity are the foundation that the diversity movement was built upon. The opposite of exclusion, inclusivity posits that we should strive to be good neighbors, to be accepting of everyone. Many diverse books touch on acceptance and fair opportunity, so our current challenge is to retain these true definitions of inclusivity and equity when describing children’s books, particularly since reality tends to creep toward exclusion.

Community and unity are recurring themes in diverse books, especially those that center ethnic/cultural ties and/or chosen families like those frequently present in the LGBTQ+ community. Even though we are several years removed from the isolation of lockdown, does it feel like we are still metaphorically “physically distancing” ourselves from one another? Diverse books can highlight communities coming together and reviving our propensity for unity.

Compromise and fairness are themes that many children’s books, diverse or otherwise, explore. Overcoming obstacles and discerning right from wrong are akin to being able to solve our problems through reasoning and mutual accommodation. Unfortunately, we are experiencing a worldwide crisis in our ability to listen and compromise. Diverse books encourage characters (and readers) to listen, talk to those who do not hold the same views, and find compromises and fair results.

Historical and contemporary discrimination are commonly depicted in diverse books. This is not a negative thing. Instead, these books mark the milestones of injustice and the work of those who fought for change and peace. These books also serve the crucial function of informing young readers of what happened in the past with the hope of not repeating the same things again. Stories of those fighting discrimination can act as bridges for teaching problem solving, conflict resolution, and critical thinking. Classrooms — whether in schools or in homes — have always been where learning happens, and if we prohibit children from engaging truthfully in their own country’s history, we rob them of their right to learn what they must know to rise and become better stewards of this world than previous generations.

And last but not least:

Books that are just plain fun. As mentioned above, diverse books do portray acts of discrimination and injustice, which is important, but these types of titles do not tell our whole story. The other aspects of historically marginalized people’s experiences include, among many other things: joy, love, tenderness, laughter, dreaming, and make-believe, all vital parts of the totality of lives depicted. To only publish books about sadness and pain would do irreparable damage to the honest portrayal of people’s lives.

* * *

In many ways, these themes are the building blocks for a civil society for us all. The intention of better representation in children’s books is not about indoctrination. It is about depicting the world as it is — warts and all. It is about honesty and truth and being able to face our history, our triumphs, and our tragedies as a people who are not perfect but are striving to be better. This is what it means to be human.

At Lee & Low, we have spent thirty-four years steadfastly publishing diverse books because we chose to fill a void with the belief that once the books were available, they would find their readers. While our instincts were spot on, it is not enough to be right. Instead of answers, we are left with questions: will “we the people” allow diverse books to be forcibly pushed aside and eradicated from schools and school libraries — even when they bring all that is mentioned above? Will we act to protect free speech and intellectual freedom? Do we value the contribution that diverse books have made? It is not too late for us to recognize and reclaim their value. As Nelson Mandela once said, “May your choices reflect your hopes, not your fears.”

From the November/December 2025 issue of The Horn Book Magazine.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!