Ashley Bryan and Jerry Pinkney: Unfettered Artists Sharing Their Talents, Visions, and Joys

Ashley Bryan (1923–2022) and Jerry Pinkney (1939–2021) are two of our most revered illustrators of children’s books. Each was prolific, with more than seventy books for Bryan and over one hundred for Pinkney, and their collective accolades include recognition by Caldecott (for Pinkney), Newbery (for Bryan), Coretta Scott King, and Boston Globe–Horn Book award committees, among many others. Although their bodies of work are quite different, there are intriguing commonalities in their experiences and worldviews.

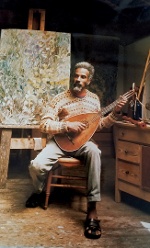

Two revered illustrators: Ashley Bryan (left; courtesy of Sandy Campbell) and Jerry Pinkney (right; photo: Robyn Pforr Ryan).

Ashley Bryan (1923–2022) and Jerry Pinkney (1939–2021) are two of our most revered illustrators of children’s books. Each was prolific, with more than seventy books for Bryan and over one hundred for Pinkney, and their collective accolades include recognition by Caldecott (for Pinkney), Newbery (for Bryan), Coretta Scott King, and Boston Globe–Horn Book award committees, among many others. Although their bodies of work are quite different, there are intriguing commonalities in their experiences and worldviews.

In interviews, talks, and presentations, both were frequently asked about nurturing and creating art when faced with racist attitudes and assumptions; the potentially soul-killing comments that questioned their abilities and society’s acceptance of their talents. Fortunately, neither Bryan nor Pinkney succumbed to the dream destroyers. They were bolstered by their families, friends, and communities; instructors who encouraged them; and individual desire and drive; and they thrived. How did they metaphorically “sing” through their art?

James A. Baldwin’s canon of novels, essays, speeches, and interviews has had a deeply profound effect on several generations. The film documenting his life, I Am Not Your Negro, captures his fiery and passionate defense of freedom. Recent examinations of his life and work articulate the prescient nature of his writings. His sense of being a free person able to share his artistic gifts serves as a way of viewing the work of Bryan and Pinkney, as evident in the following quotation from Notes of a Native Son:

One writes out of one thing only — one’s own experience. Everything depends on how relentlessly one forces from this experience the last drop, sweet or bitter, it can possibly give. This is the only real concern of the artist, to recreate out of the disorder of life that order which is art.

Bryan and Pinkney embody Baldwin’s beliefs that the totality of the artists’ experiences are needed to create, reinterpret, counter, and dream a world that allows for artistic freedom and acceptance. Both artists faced opposition from the broader society, primarily racial, that spurred their “relentless” pursuit of creative expression. They drew from traditions: canonical art and later artistic movements that sought to reshape that tradition; and an emergent tradition reflecting Blacks’ yearning for equality in all aspects of life and culture. As students of art (Bryan at The Cooper Union in the 1940s, Pinkney at the Philadelphia Museum College of Art in the late 1950s), both were likely immersed in canonical art and techniques, along with new (at the time) artistic movements. We can see these influences in their illustrations. Pinkney preferred realism with some steps toward impressionism. Bryan changed up his artistic styles, moving among influences such as realism, impressionism, and expressionism. He reveled in learning new techniques and adapting various media to them, for instance Japanese printmaking, scratch art, and lithographs.

An artist’s life can be precarious relative to generating a stable income and gaining an audience that helps promote their work. Overlay race (and gender), and the precarious nature of the art world becomes even more so. Pinkney described the reawakening of his sense of self as he became immersed in Black history and culture through new aesthetic lenses. The historic moment for the change was during the Black Arts Movement (1965–1975), which itself had roots in a fascinating past.

Following in the Footsteps of Several Generations

Black artists during the colonial era used their talents to make folk art, crafts, goods for the home, and fine art in Europe, within North America, and in colonies throughout the Caribbean and Central and South America. A groundbreaking group of artists in colonial America through the antebellum period gained recognition and, for a small number, some fame. New directions were forged by Henry O. Tanner and adherents to various schools; Robert S. Duncanson and others aligned with the Hudson River group and perspectives, and Edmonia Lewis, an acolyte of neoclassicism, might have inspired Bryan and Pinkney as they visited galleries and museum exhibits or were introduced to them through courses of study. Commonalities exhibited by each included formal training; refinement of skills working as apprentices; travel throughout the U.S., Canada, the Caribbean, and Europe; and realization of their skills shaped by shadows of discrimination such as discouragement of their desires to pursue art or denial of admissions to art schools. Their art was not likely to grace the pages of children’s literature, textbooks, or periodicals such as The Youth’s Companion or St. Nicholas. However, much of it was rediscovered in the twentieth century by scholar/artists such as Samella Lewis. These artists gaining a foothold in the art world during the Harlem Renaissance and post-WWII era helped make the path for Bryan and Pinkney a little less difficult.

Children’s literature written and/or illustrated by Blacks in the late nineteenth century through the 1950s drew upon the artistry of individuals such as Laura Wheeler Waring, Hilda Rue Wilkinson Brown, Albert Alexander Smith, Effie Lee Newsome, and Marcellus Hawkins. These artists were supported and nurtured by the triumvirate of W. E. B. Du Bois, Augustus Dill, and Jessie Redmon Fauset through the children’s periodical The Brownies’ Book, and fiction and nonfiction published through Du Bois & Dill Publishing Company and Carter G. Woodson’s Associated Publishers whose major artist was Lois Mailou Jones. Their visions of Blacks and Black life (along with standard offerings such as still lifes and landscape paintings) captured the emancipatory rhetoric of the New Negro espoused by Alain Locke. Their art was in stark opposition to art portraying Black people from the dominant culture, which showed mammies, pickaninnies, and bucks. Black artists deconstructed, reinvented, and subverted stereotypes of Blacks and Black life found in children’s literature and other cultural objects in ways that disrupted such images. Waring, Brown, and others drew images of Black children who were happy, well-groomed, intelligent, modest, and beautiful. The emerging canon of Black children’s literature nurtured by Du Bois, Dill, Fauset, and Woodson contradicted the prevailing imagery, mainly stereotypes.

* * *

Ashley Bryan "surrounded by the arts." (Photos courtesy of Sandy Campbell.)

Ashley Bryan was born in the middle of the Harlem Renaissance and grew up in Harlem and the Bronx surrounded by the arts — visual, musical, literary, and verbal. His communities were the epicenters of vibrant cultures born of a mixture mainly of native New Yorkers, migrants from Southern states, and immigrants from Europe and the Caribbean. He remained there until military service, teaching, and fellowships in other parts of the U.S. caused him to leave. Bryan would also draw on progressive artistic communities such as the Art Students League of New York for training and camaraderie. He faced many obstacles, such as art schools denying him admission because of his race. Undaunted, he continued his efforts for advanced education until he gained acceptance to The Cooper Union and, later, Columbia University.

These experiences and influences would affect Bryan’s art in ways that were foundational, cosmopolitan, and reflective of the ethos of someone open to experiences that transcended geography, gender, race, and other potential strictures. One can conclude that Bryan adopted a Pan-African perspective in that his art, folktales, puppetry, and poetry reflect the oral and sacred traditions of Africa, East and West primarily; the U.S.; and the Caribbean. His canon is a veritable artistic “triangle trade” that resulted in new world creations; e.g. spirituals, blues and jazz musical forms, and art. Military training in the South and fighting in Europe during WWII challenged his ideas about freedom to move through spaces and places in profound ways. It also fortified his connections to his fellow Black soldiers as they experienced overt racism and interacted with those facing the brutality of Nazism in Europe. Through his memoir, Infinite Hope: A Black Artist’s Journey from World War II to Peace, readers experience Bryan’s joy for life, love of people, exhilaration in language, and need to paint, tell stories, and make puppets — all of which contrast with the image of the warrior fighting for freedom and democracy. The dichotomy between war and the joy of creating art intersected in ways that shaped his creativity.

Art created from found objects has been in vogue for several decades, although its origins are in the early twentieth century. Bryan joined the movement as a child when he and his sister created art in their home after forays in the neighborhood. Their format of choice was puppetry, and they would walk throughout their community picking up discarded items. Bryan, in a 2014 interview in Publishers Weekly, shared that the state of Maine and its beaches were places of solace from the experiences and memories of war and the somewhat jarring return to New York City after WWII. Bryan received an art fellowship that allowed him to create and heal. Beaches, rather than sidewalks, became the source of found items for crafting puppets of various sizes. The visual impact of the puppets can be seen in Ashley Bryan’s Puppets: Making Something from Everything.

* * *

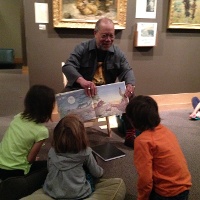

Jerry Pinkney with his sisters (left; photo courtesy of Jerry Pinkney) and

reading to children at the National Museum of Wildlife Art in Jackson, Wyoming, in 2015 (right; photo courtesy of Julie Danielson).

Philadelphia, the birthplace of Jerry Pinkney, was a cultural center with storied history and traditions of Black life. The history included a politically and culturally active and financially stable Free Black community; an active abolitionist movement; establishment of a new religious denomination, the African Methodist Episcopal Church; literary and social clubs; and some thriving businesses, such as the sailing enterprises of the Forten-Purvis families. Philadelphia offered experiences for Pinkney similar to those of Bryan’s. Pinkney’s father and grandfather did such work as painting, repair, factory jobs, and wallpapering. These occupations gave them access to drawing implements, tools, wallpaper, and other odds and ends. Fettered but not daunted, his father and grandfather encouraged Pinkney’s interest in art; their support was critical along with that of his mother and other relatives in the area and in the South.

Pinkney would immerse himself in art, expressing his innermost thoughts and dreams. His proficiency in drawing was evident early and encouraged by his teachers. Volume two of Pat Cummings’s Talking with Artists includes a picture of a bird painted by Pinkney as a child. The drawing portends his later preference for realism and personification.

Pinkney sought ways to move between, around, and through obstacles. He understood the value of community and sought to create a supportive one for himself and his friends with artistic talents. Some of his teachers did not encourage his artistic ambitions. He persevered, and honed his skills in drawing and painting and formed friendships with two other Black students who were artists. A chance meeting with cartoonist Jon Liney then led to a type of mentorship, with Liney guiding Pinkney in understanding the ways to make a career in art economically viable. Pinkney’s post-secondary training in art was acquired at the Philadelphia Museum College of Art. Upon graduation, Pinkney worked for a greeting-card company and moved into illustration in 1964.

Artistic Philosophies

Bryan’s and Pinkney’s ideas about art and creativity intersect and diverge in interesting ways. They were each deeply enmeshed in acquiring knowledge about artistic styles and skills and developing a personal theory of art. Encouragement from family, friends, and community ensured that their talents were nurtured, including the provision of art supplies and materials. Formal art education as children and young adults enabled them to compete with others seeking post-secondary admissions. Each faced obstacles based on race, but those experiences were not internalized. Rather, their determination intensified, and they would counter opposition with understanding and love through their art. They traveled widely. The awakening of racial and ethnic pride drawn from Africa, the Americas, and Caribbean regions’ cultures, history, folk traditions, music, foods, and achievements in arts, science, and history were critical to their development. The pride engendered within them was ignited in new ways as some of their works were centered in Blackness.

Bryan was a Pied Piper in many ways. I discovered this quality in the late 1980s at The Ohio State University’s Children’s Literature Conference. Bryan was a keynote speaker whose voice ranged from a soft whisper to a song-like cadence, and, surprisingly, a shout. He accompanied his voice with a recorder, handclaps, and music. I was mesmerized by the centrality of voice in his presentation. Another anecdote symbolizes his fiercely protective stance toward Black cultures and Black people. I served on an advisory board for the Addy books in the American Girls Collection series published by Pleasant Company. Addy, the first Black character in the series, has a doll created by her mother, a doll from bits and pieces of vegetation, yarn, textiles, earrings, and a cowrie shell necklace. Bryan had favorable comments about the stories but chastised me about Addy’s doll in the illustrations. He characterized it as ugly, a distortion of physical features, and a stereotype. (I apologized and told him I would talk with an editor about the doll and assured him that, in the future, I would be more assertive in my critiques.)

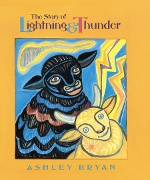

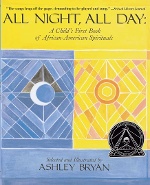

Bryan often spoke about the centrality of the arts to his ideas about the roles of art in the lives of all. Foremost was the belief that art was not a commodity for a small elite group. Art was, as he put it, “a part of being human and being a whole person.” He actualized this critical perspective through presentations to children and adults, teaching, puppetry, and storytelling. Another catalyst recounted by Bryan was his experiences in kindergarten. There, he learned the alphabet, numbers, and words by creating books in class. Ironically, his teacher conveyed several key elements of “scientific reading instruction” through a whole language philosophy. He learned that sound or orality were vital to learning to read as well as to art and music. Bryan immersed himself in the oral traditions, e.g., folktales, songs, music, proverbs, poetry, in each country he visited and those in which he found interest through inquisitiveness or friendships. Books such as The Dancing Granny, The Story of Lightning & Thunder, and All Night, All Day demonstrate a philosophical stance about the need to bring the tales to life through orality and art that evokes their essence and spirit. Folktales also connected Bryan to the African diaspora in the United States and the Caribbean with Africa as the point of origin and centrality.

Bryan’s beliefs about cross-racial and cultural interactions were cosmopolitan and transformative. He embodied the idea of fluidity, in and out of cultures nurtured by respect, honor, and connection, intellectual and spiritual. Black artists and writers were integral to cultural interaction in publishing. Bryan stated, “When Blacks opened the door, it’s opened to everyone.”

Pinkney’s ideas about art and its function begin with the personal. His family fostered his abilities through praise for his drawings, and, equally importantly, the materials to create and space within which to draw. Pinkney spoke often about some difficulty with print that was later diagnosed as dyslexia. One way of avoiding the struggle with print was through drawing, and he devoted significant time and intensity to art. Thus, he was able to read the world through visual imagery.

Another cornerstone was the adherence to excellence in skills such as drawing the human form or animals, using different types of paints but focusing on watercolors, and translating language in corresponding visual images. Folktales he illustrated capture a range of emotions and movements; for example, The Talking Eggs (written by Robert D. San Souci), The Tortoise & the Hare, and Sam and the Tigers (written by Julius Lester) include wonderment, fear, greediness, and happiness. The picture book Back Home, created in collaboration with his wife, Gloria Jean Pinkney, connects to fundamental aspects of Pinkney’s artistic visions: love for family; love of art and sharing it with others; exploring African American and African history, cultures, and creative arts. In Sam and the Tigers, Pinkney successfully subverted and reimagined some of the most entrenched stereotypes of Blacks in the U.S. and in cultures throughout the world. His intent was to “take away the sting of earlier editions of Sambo while capturing the style, dignity, and uprightness of Blacks.” Further, a fundamental tenet is to “expose how African Americans live, love, and care about themselves.” None of his illustrations are stereotypes, including those featuring animals.

Legacies: Firmly Ensconced in Art Canons

Importantly, Bryan and Pinkney’s major legacy has been the provision of aesthetic pleasure to readers and viewers. Their illustrated books are firmly ensconced in children’s literature canons. The numerous awards accorded them cement that status in a way that readers’ responses, reviews, and word-of-mouth alone could not. While significant amounts of their work were centered in their own cultural identities, another subset crossed racial and cultural identities. It would be unfair to characterize the crossings as going mainstream. I believe both would have argued that their racially and culturally centered art was universal as well. Also, Bryan’s work as a storyteller and puppeteer is likely to gain a greater appreciation and critical examination as it is shared. A namesake institution for Bryan, the Ashley Bryan Center, preserves his legacy’s visibility through future generations, especially his paintings not used in picture books and his puppetry. An uncommon way that Pinkney’s legacy is ensured is the eleven stamps he created for the United States Postal Service’s Black Heritage series.

Both creators have devoted followers among readers, teachers, and librarians, who intentionally and consciously share their work. Bryan and Pinkney were frequent presenters and honorees at the American Library Association, International Reading Association (now International Literacy Association), and National Council of Teachers of English conferences. They often appear on recommended reading lists, which will introduce new generations of readers to them.

Most of the artists in whose footsteps they walked taught in elementary and secondary schools as well as in colleges and universities, especially HBCUs, along with state and Ivy League institutions. Bryan and Pinkney followed this tradition. Teaching enabled them to impart their knowledge and experiences to eager aspiring artists. Each formed mentoring relationships and friendships. Not all were visual artists; writers such as Jason Reynolds have also viewed them as inspirations.

They are part of the ongoing efforts to institutionalize work begun in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, which chipped away at systemic strictures to create spaces for Black artists and offered works that elucidate the reasons Black artists “sing.” They did so in ways that did not compromise their visions, ideals, and cultures.

From the November/December 2022 issue of The Horn Book Magazine.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!