CCBC and Diverse Books: Numbers Are Just Part of the Story

At the Cooperative Children’s Book Center (CCBC), we know there is great interest in the statistics we release every year about diversity in children’s and young adult literature. From the very beginning of our work documenting aspects of diversity in books for youth, we’ve understood that the numbers are part of a much bigger story, one that stretches back far beyond the nearly forty years we’ve been releasing numerical data, and one that is about much more than numbers.

At the Cooperative Children’s Book Center (CCBC), we know there is great interest in the statistics we release every year about diversity in children’s and young adult literature. From the very beginning of our work documenting aspects of diversity in books for youth, we’ve understood that the numbers are part of a much bigger story, one that stretches back far beyond the nearly forty years we’ve been releasing numerical data, and one that is about much more than numbers.

Looking Back: A Brief History

The CCBC is a statewide resource library for children’s and young adult literature in Wisconsin, providing education and outreach, and serving as a statewide book examination center. It is in this latter role that we receive review copies from publishers, and it is these review copies that make what we do around diversity in literature for youth possible.

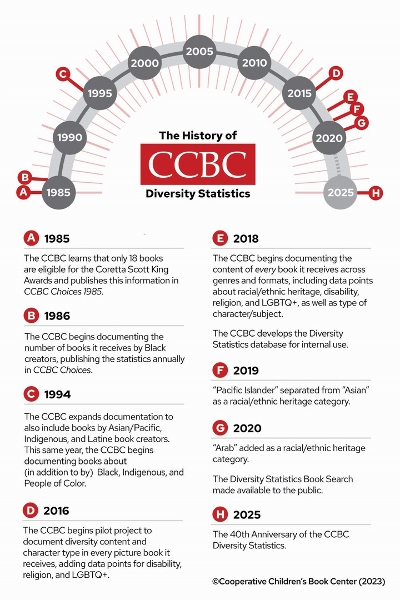

The CCBC’s history of documenting diverse books began in 1985. That year, then–CCBC director Ginny Moore Kruse, serving as a member of the Coretta Scott King Book Awards Jury, was appalled to learn that only eighteen of the approximately 2,500 new books published for children and teens that year were created by African Americans. This is what inspired the CCBC’s efforts to document the number of books by Black authors and illustrators annually. Beginning in 1994, we began keeping track of the number of books we were receiving by Asian/Pacific, Indigenous, and Latine book creators as well. That year we also began documenting not only the number of books created by Black, Indigenous, and People of Color, but the number of books about Black, Indigenous, and People of Color, including the many titles in the latter category that have been created by white authors and/or illustrators.

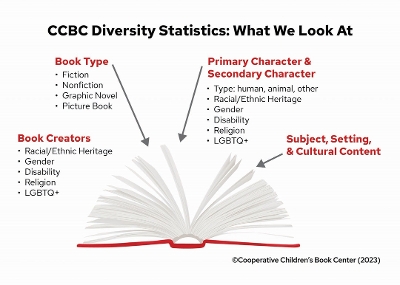

In 2018, we made another huge change, the result of two years of discussion and planning, when we shifted from counting only books by and/or about BIPOC to documenting the content of every book we receive. We now provide an analysis that captures character type (human, animal, other, none), as well as data about race/ethnicity, religion, disability, and LGBTQIA+ content with regard to subjects/characters. We also capture these aspects of identity for book creators. Our determinations are based on examination of the text and illustrations in shorter books and the text along with information provided in professional reviews of longer books; we also research the creators. We are as specific as possible based on the information we find in the books or reliable sources (e.g., author interview or website). More information about what and how we document can be found in our “Diversity Statistics FAQs” on the CCBC’s website.

Our work is informed by deep, ongoing discussions that the CCBC staff have been having internally for years, and by critical input and insights we’ve gained from those outside the library. This is why some of the terminology and categories we use have changed across the years. We strive to reflect the preferences of those whose identities we are documenting, especially as articulated in the current discourse and opinions of content experts from those identity groups in our field even as we understand that there isn’t always consensus, nor ought there be.

Key Points and Common Misconceptions

The longer we have been doing this, the more we discover how difficult it is to convey the complexity of the data in whole or in part. Perhaps the most often-missed key point about our statistics is the simplest one to clarify: we do not receive everything published for children and teens each year. It’s why we always make clear the number of books we analyzed (prior to 2018 this was a solid approximation; since 2018 it’s been exact). We are confident that what we do analyze is a more-than-significant sampling; it’s why comparing percentages of the whole rather than number of books from year to year is critical.

We capture many data points about individual books and creators (see images on pages 24 and 26). The complexities of these various data points are myriad. For example, we capture the intersectionality of individual characters. However, in a numerical chart, intersectionality disappears, and it isn’t clear that a single book or single character in a book may be counted in two or more data points for a single category (e.g., Black/African and Latine; neurological disability and physical disability). Likewise, multiracial creators and characters are counted in all applicable categories (e.g., an Afro-Latine individual is counted in both the Black/African and Latine categories; the exception to this is when a multiracial creator’s race includes “white.” In such a case, the individual is not counted as a white creator).

While we strive to be consistent, there is always a degree of subjectivity, especially in analyzing illustrations. We might be uncertain whether a child looks light-brown-skinned or white. If the author or illustrator identifies as Chinese American, can we assume this dark-haired, dark-eyed child pictured in the book is also Chinese American? (Our staff is currently composed of four white librarians; we carry that awareness into our engagement with this work every day.) For many of the novels, we are especially indebted to information provided by Kirkus, which made the editorial decision, intended to address “white default,” to identify race in every one of their children’s and young adult reviews; and by other professional review outlets. Our small staff reads many books, but we certainly can’t read every novel published in a year.

This is why we focus on capturing data in categories that can be clearly defined. Even as we sometimes struggle to decode something in a specific book, we are clear on the categories themselves. This is not to say we are locked into rigid understanding. Listening and learning and being open to change are essential; feedback and input from others and our own research have led to changes over time, such as when we separated “Pacific Islander” from “Asian” (2019) and when we added “Arab” (2020). Trying to delineate the content of books around concepts that are open to interpretation, such as what defines a particular class status or whether a book’s setting is rural or urban (a recent suggestion), while valuable, is not suited to the type of analysis we are doing. Additionally, our focus is on aspects of identity that individuals possess regardless of these and other aspects of their lives.

Not Just Quantity, but Quality…

As noted elsewhere in this issue, the past decade has seen a significant increase in the number and percentage of diverse books published for children and teens, and the number of diverse book creators. This is something to celebrate, and it is a direct result of the greater visibility of activists and advocates in many fields that intersect with children’s and young adult literature, whether on social media or in journal articles, the mainstream media, or elsewhere. Their work is part of a movement and a call that stretches back decades, and like many of the voices speaking today, those earlier activists (librarians, educators, critics, scholars, creators, and others) weren’t just asking for more, they were asking for better: better books, with authentic voices and authentic representation.

That’s something our diversity statistics cannot capture. The CCBC’s work has always been about much more than the quantitative analysis that goes into compiling our annual statistics. Since 1980, we’ve created an annual best-of-the-year list, CCBC Choices. And Choices, which grows out of the reading we do critically throughout the year and forms the core of our outreach efforts and the content of the CCBC-Recommended Books Search database on our website, has always included diverse books, because even when the number of diverse books was far fewer than what we see today, there has always been excellence among them.

The Association of Jewish Libraries knew this when it established the Shirley Kravitz Children’s Book Award in 1968, later renamed the Sydney Taylor Book Award. Glyndon Flynt Greer, Mabel McKissick, and other Black librarians who founded the Coretta Scott King Book Award in 1969, first given 1970, knew this, too, as did Oralia Garza de Cortés and Sandra Ríos Balderrama of REFORMA, co-founders of the Pura Belpré Award, first given in 1996. Many others have been established in years since. Today we count seventeen identity-based children’s and young adult literature awards and annual lists from library and education organizations within and beyond the American Library Association and its affiliates. The work of these organizations and groups is both a reflection of and impetus for excellence in diverse books for youth.

Of course, the increase in the number of diverse books being published not only means there are more diverse books available, and more diverse book creators getting contracts as writers and artists for children and teens, but also that there are more diverse books being recognized for their quality and relevance and being purchased for libraries and classrooms today.

…and Impact

At the same time, it’s impossible to talk about diverse books today without also talking about the fact that they are coming under attack; they are the focus of censorship attempts across the country. We see it firsthand, on a weekly basis, in our work around intellectual freedom in Wisconsin. The CCBC provides information and consultation for Wisconsin librarians and educators dealing with book concerns and challenges, and while the specific details are confidential, we can report that the number of requests for assistance tripled over the past two years, and the reasons for complaints mirror the trends documented by the ALA Office for Intellectual Freedom on its annual list of top challenged books.

We believe these two things are absolutely connected. When someone walks into a library or classroom today, those spaces look different than in the past. The welcome increase in the number of diverse books has resulted in their greater visibility in libraries and classrooms, and in the lives of children and teens. That visibility is something to celebrate. Unfortunately, it has also made many books targets — flashpoints in the social and political conflicts of our times, without consideration for the children and teens they’re intended to reach.

This is especially true of books about LGBTQIA+ and BIPOC lives and experiences, as well as of books that acknowledge how the racism in our nation’s present is connected to our nation’s past; in other words, books that affirm the lives and realities of children and teens today, including those who are among the most vulnerable in our communities.

Looking Forward: What Does the Future Hold?

When the CCBC began this work, the concept of intersectionality had not yet been named and defined by Kimberlé Crenshaw. Also, the number of books for children and teens with diverse characters, diverse content, and diverse creators was far smaller than it is now.

It’s so exciting to see the complex, intersectional identities of children and teenagers reflected in books today. Yet we feel the inherent tension in breaking complex content and intersectional identities down into data points.

We don’t expect our data to resonate with everyone, and we find ourselves asking if there is a point when our data will no longer be valuable or useful to those who have found it so in the past. If so, how will we know when we’ve reached it?

In 2025, it will be forty years since the CCBC first made note of those eighteen books by Black creators published for children and teens in 1985. What will publishing for children and teens look like when we reach fifty years from that date and beyond? Whether we will still be doing our work around diversity statistics the way we are now, doing it differently, or doing it at all is impossible to say. We do know that support from publishers who send us review copies will always be essential to both our diversity analysis and our ability to read and recommend diverse books. We know that getting feedback from colleagues around Wisconsin and nationally is essential to our ability to remain informed about and responsive to both current discourse and the needs of children and teens who are hungry for books that let them see and be seen. What we can say is this: we are committed to making sure diverse books — reading them and recommending them to librarians and teachers — remains a core dimension of what we do.

For more information, visit ccbc.education.wisc.edu.

From the May/June 2023 special issue of The Horn Book Magazine: Diverse Books: Past, Present, and Future.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!