Field Notes: The Day the Book Banners Came for Us

When our head of youth services came up to me one Thursday afternoon this spring and said, “I want to show you something,” I thought it was going to be something normal for the mid-sized suburban public library I run in Henrietta, New York — like a clogged toilet or an ailing plant. Instead, she pulled out her phone and showed me a Facebook post.

When our head of youth services came up to me one Thursday afternoon this spring and said, “I want to show you something,” I thought it was going to be something normal for the mid-sized suburban public library I run in Henrietta, New York — like a clogged toilet or an ailing plant. Instead, she pulled out her phone and showed me a Facebook post.

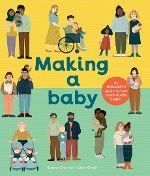

A patron had been in the library the previous evening and had spoken to a few staff members regarding her concerns about the picture book Making a Baby, written by Rachel Greener and illustrated by Clare Owen. I wasn’t onsite when this happened, but the staff had reported the interactions to me because they thought I’d be hearing from the patron. Just the month before, our library had updated our materials reconsideration procedure, and we’d retrained the staff. It sounded to me like my colleagues had responded professionally and explained our process well. I expected the patron to submit a completed reconsideration form, and then we’d get a chance to reevaluate the inclusion of the book in our collection. I looked forward to it, even — conversation and inquiry around collection choices is healthy for a library. It’s important to test our policies and procedures to make sure we stay centered in them.

A patron had been in the library the previous evening and had spoken to a few staff members regarding her concerns about the picture book Making a Baby, written by Rachel Greener and illustrated by Clare Owen. I wasn’t onsite when this happened, but the staff had reported the interactions to me because they thought I’d be hearing from the patron. Just the month before, our library had updated our materials reconsideration procedure, and we’d retrained the staff. It sounded to me like my colleagues had responded professionally and explained our process well. I expected the patron to submit a completed reconsideration form, and then we’d get a chance to reevaluate the inclusion of the book in our collection. I looked forward to it, even — conversation and inquiry around collection choices is healthy for a library. It’s important to test our policies and procedures to make sure we stay centered in them.

Instead of filling out the form, though, the patron had taken to Facebook with a lengthy public post about the book and our library that went mildly viral, generating a large number of likes, shares, comments, and additional posts. I’ve worked in public libraries for twenty-six years, and I’ve seen a lot of things, but I was shocked by what I was reading in those posts, which were livid and full of profanity. It started with complaints about the level of information contained in Making a Baby, a book about human reproduction, and quickly descended into objections to biracial and same-sex couples being pictured in the illustrations. One Facebook commenter complained that the book depicts a father who uses a wheelchair.

The situation soon escalated: the library was “grooming” children, the children’s librarian was a pedophile, “woke librarians” were idiot tools of the liberal left. I was mentioned by name many times, and then, surreally, people fabricated conversations they claimed to have had with me. There was a long Facebook exchange about our board that included one person who said the board was “all gay” and another who posted a vomiting emoji to express her feelings about its diverse composition. People talked about stealing this book and other books they found objectionable (primarily books with LGBTQ+ content) from our shelves and burning them. By the time I saw this thread, my staff was already sharing it with one another, and so I spent the entire next day trying to calm them down.

* * *

Photo: Adrienne L. Pettinelli.

Several years ago, our library went out to a public vote to build a new facility. The proposition passed, and we opened our new building three years ago — a successful project on many levels. It was during the informational campaign for that vote, though, that I learned that the internet and social media aren’t always fun. Prior to that, I’d happily participated in vibrant online communities and made friends that I hold dear. But when we were building our library is when I started seeing the side of the internet where people lie and sow discord and behave in antagonistic ways. I saw that words online are not throwaways; they have implications and consequences. They can cause real harm.

I mention this because a couple of days after the patron wrote her Facebook post about Making a Baby, a man I’d never met copied me on an email he sent to the county sheriff’s office asking it to investigate the library for allegedly distributing pornography, offering as evidence a few photos of illustrations from the book that he had pulled not from visiting the library or from the book itself, but from the original Facebook post. I knew my library was not distributing pornography — particularly not in the form of this children’s nonfiction picture book with cartoon-style illustrations — but also, I was frightened. This stranger, who seemingly doesn’t even use the library, meant us harm; meant me harm. I was home when I read this email, and I’m glad I was, because I cried, and I couldn’t stop shaking for an hour.

Our town supervisor in Henrietta is an avid reader and writer, and also a person I trust, so when things started spiraling, I contacted him. He found and read the Facebook posts and commented on some of them in defense of the library’s practices and the inclusion of a book like this in our collection, and almost immediately people started editing and deleting the things they’d written. I am not sure if these people had commented without realizing how visible the posts were or if, once they got past being caught up in a moment, they realized they’d said things they didn’t want to stand behind, but much of what I initially saw is now gone.

Of the dozens of people involved in the online discussion about whether or not this book should be in our library, I saw comments from only one person who displayed a true knowledge of the book, as if she’d read and spent time thinking about it. The original poster took photos of select pages while she was in the library and shared them online; the entire discussion was based on those photos. It has always been the case that few people who challenge books read the books they’re challenging in their entirety. They see or hear about something that surprises or shocks them, and they begin their efforts to suppress the book and, I think, their feelings.

But here’s the thing — whatever books we have in our library, whatever policies and procedures we use, people exist. Queer people exist. People of color exist. Parents in wheelchairs exist. Frightened book banners exist. Conspiracy theorists exist. It’s easy to write a bunch of angry things on Facebook and delete them later. It’s easy to try to ignore things one doesn’t like. For my part, I can’t pretend that some of these folks who caused my colleagues and me so much angst aren’t people in our community; some use our library regularly and are people with whom I’ve had any number of positive interactions. It is right and proper to have conversations about a book, but the way this happened to us — the way I know it’s happening in libraries and to librarians across the country — is outside of anything I could have imagined ever happening back when I decided to go to library school.

There was one woman involved in all this who gave me hope. I don’t know if she read Making a Baby, but when she saw the original Facebook post, she reached out directly to the library with an alarmed but polite email about the book. She was the only person who chose this path. She and I had a pleasant email exchange in which I explained our reconsideration process, and she expressed her perfectly legitimate concerns about the welfare of children in contemporary society. This was a point we found we could agree on — we both care deeply about children getting a positive, healthy start in life. A week after that exchange, I hadn’t seen a reconsideration form from her, so I called to make sure I hadn’t missed it. She was pleasantly surprised that I reached out. She let me know she’d filled out the form, but her kids had been sick and so she hadn’t been able to drop it off. I encouraged her to submit the form electronically, which she did.

That’s what’s supposed to happen. People are supposed to talk to each other.

* * *

The sheriff’s office seems to have determined that Making a Baby is not pornography. The hubbub has died down. Our two copies of the book remain in our children’s collection, and I check on them periodically to make sure they don’t wind up stolen. I’m not naive enough to think this is over.

I’ve been telling a lot of people about this experience. This is partly because I’m still trying to understand it, and also partly because I can. Many librarians in these situations don’t speak up because they have to worry about their employment and safety on top of the overt and covert threats to the library itself. This makes the voices of those who would ban books feel much louder than those of the people whose job it is to make books and ideas widely available. I am fortunate. I have worked in the same town for a decade, and our library is a trusted and highly regarded institution. Our town politicians are readers who use the library, and politicians from both parties reached out to offer support to the library and its mission when all this happened. I am grateful for this beyond measure; in today’s highly charged climate, I know my experience is not the norm. This support of public libraries as places where all people deserve equal weight and respect, where we do not suppress thoughts and ideas, is a critical piece of how our democracy is supposed to function.

Public libraries in the United States have historically done a poor job of fully representing and supporting all the voices in our communities. The philosophy of “give them what they want” that has prevailed through much of my career served in many ways as a tool that upheld and strengthened systemic inequities and oppression. Now I hope and believe that many of us are seeking to correct our failures, and we’re bringing forward voices some people haven’t wanted to hear, voices some people aren’t used to hearing, and that’s what this whole incident was about. Some people saw biracial couples in a children’s book, and they reacted with rage. They saw two dads, and they reacted with rage. Not everyone who sees something that challenges their worldview reacts with rage, but some do. Not everyone who wants to ban books wants to rid the world of certain types of people, but some do. Not everyone who posts angry things on the internet means to harm actual human beings, but I live an hour from Buffalo, New York, where a young man who spent a lot of time posting angry things on the internet walked into a grocery store on a Saturday afternoon and murdered ten Black people while they were shopping.

Some people mean harm.

I don’t have a tidy conclusion here. People said terrible things about a book, my library, the people who work in my library, and the people who use my library. They threatened to do things that ultimately have not come to pass, and that wasn’t because of anything we did or even could do. We were lucky.

From the September/October 2022 issue of The Horn Book Magazine.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!