Getting There: Taking a Trip Through Queer Kidlit

“What is your critical axe to grind?” That’s the question our professor, without much preamble, asked the two of us in our first children’s literature graduate seminar together. She explained that our “critical axe” was the thing (and we’re paraphrasing here) about youth literature that had us in a chokehold. Several things fit this description for us then — and the list grows even now.

“What is your critical axe to grind?” That’s the question our professor, without much preamble, asked the two of us in our first children’s literature graduate seminar together. She explained that our “critical axe” was the thing (and we’re paraphrasing here) about youth literature that had us in a chokehold. Several things fit this description for us then — and the list grows even now. Almost exactly ten years later, at least one axe is the same that we (and so many others) are still grinding today: if we’re ever gonna get anywhere, queer youth literature needs to be read for filth.

“What is your critical axe to grind?” That’s the question our professor, without much preamble, asked the two of us in our first children’s literature graduate seminar together. She explained that our “critical axe” was the thing (and we’re paraphrasing here) about youth literature that had us in a chokehold. Several things fit this description for us then — and the list grows even now. Almost exactly ten years later, at least one axe is the same that we (and so many others) are still grinding today: if we’re ever gonna get anywhere, queer youth literature needs to be read for filth.

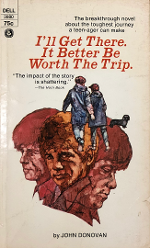

By now, most people know that early LGBTQIA+ youth publishing was obsessed with trauma. In the first YA novel featuring gay characters, John Donovan’s I’ll Get There. It Better Be Worth the Trip (1969), a car kills a gay teen’s beloved dog soon after his mother discovers him in bed with another boy. As first times go, that’s rather a low bar. The first queer picture book, Jane Severance’s When Megan Went Away (1979), is similarly traumatic if a bit more hopeful: a lesbian couple separates, and the child and mother left behind comfort each other. A story that represents a queer family but only as it is coming apart manages to feed two very tricky birds with one scone. Or perhaps feed the one bird so it doesn’t notice it is itself being eaten by the other.

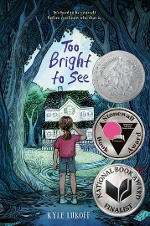

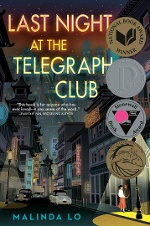

Happily, though, queer excellence defines the current moment. In addition to We Need Diverse Books’s impact on the field, several blogs have both borne witness to and pushed for change: Mombian; LGBTQ Reads; Lee Wind’s blog and queer lit resources; YA Pride; and Malinda Lo’s blog and queer YA statistics. Social media in general has been an important forum to share critiques both positive and negative, yielding undeniable results. And while LGBTQIA+ books have occasionally garnered major literary award recognition, 2022 was a banner year. In what he termed “Newstoneberywall,” Kyle Lukoff became the first trans author to be recognized by both the Newbery and the Stonewall (not to mention the National Book Award for Young People’s Literature) committees for the same book: Too Bright to See. Lesbian author Malinda Lo was recognized by the Stonewall, Asian/Pacific American Award for Literature, Printz, and NBA committees for Last Night at the Telegraph Club. The excellence continues into 2023, as the slate of Printz Honor Books all contain LGBTQIA+ representation. (That’s a lot of silver but, alas, not nearly enough gold.) It’s not only quality but also quantity: the 2023 Rainbow Book List has over 190 titles compared to the forty-five on the inaugural 2008 list.

Happily, though, queer excellence defines the current moment. In addition to We Need Diverse Books’s impact on the field, several blogs have both borne witness to and pushed for change: Mombian; LGBTQ Reads; Lee Wind’s blog and queer lit resources; YA Pride; and Malinda Lo’s blog and queer YA statistics. Social media in general has been an important forum to share critiques both positive and negative, yielding undeniable results. And while LGBTQIA+ books have occasionally garnered major literary award recognition, 2022 was a banner year. In what he termed “Newstoneberywall,” Kyle Lukoff became the first trans author to be recognized by both the Newbery and the Stonewall (not to mention the National Book Award for Young People’s Literature) committees for the same book: Too Bright to See. Lesbian author Malinda Lo was recognized by the Stonewall, Asian/Pacific American Award for Literature, Printz, and NBA committees for Last Night at the Telegraph Club. The excellence continues into 2023, as the slate of Printz Honor Books all contain LGBTQIA+ representation. (That’s a lot of silver but, alas, not nearly enough gold.) It’s not only quality but also quantity: the 2023 Rainbow Book List has over 190 titles compared to the forty-five on the inaugural 2008 list.

* * *

Times change, and it can be tempting to throw out some of LGBTQIA+ publishing’s embarrassing childhood photos in favor of its revolutionary glow-up. But the power of revolution is grounding a vision for the present and future in the struggles and joys of the past.

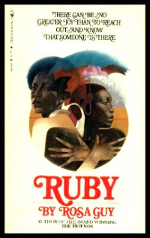

That inciting year of gay YA — 1969 — was the year of the Stonewall Riots. We owe our rights and progress to trans women of color’s radical rage, yet cisgender white gays, such as Donovan’s protagonist, became, for a long time, the face of the movement (and our books). Michael Cart and Christine A. Jenkins’s research shows that it took an additional seven years before the first lesbian YA novel was published (Ruby, 1976). We waited, per Cart and Jenkins, twenty-one more years for the first bi YA novel (“Hello,” I Lied, 1997) and twenty-eight for the first trans YA (Luna, 2004). We didn’t see mainstream YA about the other letters in the LGBTQIA+ acronym until 2014 and beyond, which is about when LGBTQIA+ middle-grade novels started to proliferate. Some identities have yet to appear in print at all. In this endless cycle of firsts, why are we still — over fifty years later — waiting for seconds or thirds? There is no such thing as a natural phenomenon in youth publishing — every trend and pattern we see is by design. The answer to our “why” lies in asking: whose interest does the current design serve?

* * *

Mainstream publishing, as the literary arm of society’s prejudice, has long rejected queer representation beyond conformity. Jennifer Miller’s research on LGBTQIA+ picture books shows that, overall, early books largely focused on white, middle-class, queer, cisgender parents in normative nuclear family structures, such as the classic Heather Has Two Mommies. Occasionally, a gay uncle would visit as an outsider who either had HIV/AIDS (pre-2000) or a new husband (post-2000). Besides these parents and “guncles,” other queer adults have rarely appeared in picture books until recent years. This is unfortunate, given that queer families often extend into found families and larger queer communities. As Miller’s research further shows, queer and trans children — beyond coded, gender nonconforming “sissy/pink boys” and “tomboys” — have also been slow to appear in picture books (starting with Marcus Ewert’s 10,000 Dresses, 2008).

LGBTQIA+ publishing for younger readers often lags behind YA (that’s a whole other essay!), but there have been some more key firsts. At this point, though, we’d rather call them “finallys.” We finally saw the first picture book to feature a queer boy’s crush (Jerome by Heart, 2018) and, four years later, a queer girl’s crush (Love, Violet, 2022).

We also finally saw:

- the first middle-grade anthology;

- the first picture book about an overtly queer grandparent;

- picture books about trans kids;

- picture books about pronouns and concepts like the Gender Wheel;

- board books with actual photographs of LGBTQIA+ people;

- picture books by and about drag performers;

- nonfiction books about and beyond Stonewall, spotlighting prominent LGBTQIA+ people and histories.

* * *

As mentioned, queer kidlit is having its moment, and we are here for it. Without diminishing the enormous progress that has been made, we acknowledge that the present is not perfect. Here are a few things we’d like to see going forward, with the caveat that the multitudes of queer narratives produced should not be a zero-sum game. We say more, more, more. (The only thing we need fewer of are straight-gaze reviews.)

More journeys without closets. While we recognize that coming out will remain an important milestone for many LGBTQIA+ individuals, it is not a universal experience. Nor should that detail be required for a book (or its creators) to “count” as canonically queer. We need more books that go beyond the coming-out narrative and explore other experiences of queer discovery.

More queer communities. We want to see more books that apply queer lenses to what families can (and do) look like. Queer community is especially important, given how often queer youth and adults alike are portrayed as the only gays in town. Along these lines, we’d love more intergenerational voices.

More incidental queerness. As queer people, we get good at looking for subtext and seeing what may not be confirmed on the page. But we shouldn’t always have to. To paraphrase Kyle Lukoff, incidental queerness is only partial identity. We need more books where queerness is integral to the story but without being a source of conflict. The sweet spot: characters that aren’t interchangeable minorities (and therefore good, culturally specific representation) and plots that prioritize affirming LGBTQIA+ readers rather than educating others.

More early readers and young chapter books. When Charlie & Mouse (2017) by Laurel Snyder, illustrated by Emily Hughes, was published, there was buzz over a single page that included gay neighbors. That’s great, but a single page is not enough. LGBTQIA+ representation has since appeared in other more recent series (Mermicorn Island; Whale, Quail, Snail; Mermaid Days), but creature stand-ins, appealing as they are, aren’t the same as authentic representation. Where are the queer humans in books for emerging readers?

More intersectionality. Queer people have multiple identities and, as we’ve shown, the white, cisgender, queer experience is not universal. We want BIPOC characters who are not filtered through a white gaze, a trope author Ashia Monet has written about. We also want more disabled and neurodivergent queer characters. We want celebration, slice of life, and struggle. If the reality of a teen who is blind, Black, queer, autistic, and thriving is “too much,” then readers can go find less. A book cannot have too many identities to be “believable.”

More tropes and genres. Tropes often get thrown out as bad things, something the cultural consciousness gets tired of. No trope is overdone until marginalized communities get to use it too. That means more than once. LGBTQIA+ YA fantasy and historical fiction have been on the rise, and there has been a recent uptick in horror. This has in no small part been driven by Black queer protagonists and other BIPOC queer characters, and we love to see it.

In conclusion, we’re getting there. Finally. And with young readers’ queer and trans representation (and rights) under fire from reactionary groups wielding book bans with alarming efficiency, there’s no better time than now to uplift our books, grind our axes, and raise our bricks.

From the May/June 2023 special issue of The Horn Book Magazine: Diverse Books: Past, Present, and Future.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!