The “Vaccine” Is Here: Reading as a “Social Inoculation” for the Future of STEM

Warning — the coming sentence might make you believe you have stepped into a time warp, so hug a book and brace yourself. Today’s girls will be left behind in computing, tech, science, engineering, and math-related jobs, unless we socialize our girls to believe in their STEM abilities by fostering a sense of belonging.

Warning — the coming sentence might make you believe you have stepped into a time warp, so hug a book and brace yourself. Today’s girls will be left behind in computing, tech, science, engineering, and math-related jobs, unless we socialize our girls to believe in their STEM abilities by fostering a sense of belonging.

Sounds old-school, right? Surely girls raised in today’s modern American homes feel like they belong in science-based academic fields. Sadly, that is not the case. In fact, research funded by the National Science Foundation reveals that, “the gender gap in science and math performance has been closing but the gap in STEM self-concept and aspirations remains large.” The American Institute of Physics’ 2019 report “Women in Physics and Astronomy” supports this claim, saying, “Women remain under-represented among physics bachelor’s degree recipients. According to our 2017 Enrollments and Degrees Survey, over 8500 students were awarded bachelor’s degrees in physics, and 21% of degrees were earned by women. Although the number of women earning physics bachelor’s degrees has steadily increased over the last decade, the percentage of women has not increased.” Furthermore, according to the Harvard Kennedy School, Women and Public Policy Program, “Only 26 percent of graduate students are female in the physical sciences, and only 18 percent of full professors in STEM departments at research universities are women.” This gender gap of women in STEM isn’t just an American problem, it’s a global issue.

Sounds old-school, right? Surely girls raised in today’s modern American homes feel like they belong in science-based academic fields. Sadly, that is not the case. In fact, research funded by the National Science Foundation reveals that, “the gender gap in science and math performance has been closing but the gap in STEM self-concept and aspirations remains large.” The American Institute of Physics’ 2019 report “Women in Physics and Astronomy” supports this claim, saying, “Women remain under-represented among physics bachelor’s degree recipients. According to our 2017 Enrollments and Degrees Survey, over 8500 students were awarded bachelor’s degrees in physics, and 21% of degrees were earned by women. Although the number of women earning physics bachelor’s degrees has steadily increased over the last decade, the percentage of women has not increased.” Furthermore, according to the Harvard Kennedy School, Women and Public Policy Program, “Only 26 percent of graduate students are female in the physical sciences, and only 18 percent of full professors in STEM departments at research universities are women.” This gender gap of women in STEM isn’t just an American problem, it’s a global issue.

Comprehensive studies have proven that low representation of girls in STEM classes and women in STEM careers has nothing to do with intelligence or ability and everything to do with an important social stranglehold — girls’ lack of a sense of belonging. Furthermore, low representation creates a cycle of low numbers — girls who do not see women reflected in STEM are less likely to pursue STEM careers. However, children’s literature can be part of the solution of enhancing representation. Brain science and fMRI studies reveal that books can artificially ramp up representation and provide a sort of “social inoculation” to increase girls’ sense of belonging in STEM.

Some argue that girls just need to be brave and show up in STEM classes. In February 2016, Reshma Saujani, founder of Girls Who Code, gave a compelling Ted Talk titled “Teach Girls Bravery, Not Perfection.” She proposes that girls need to learn to be brave, to take risks, to shed the shackles of perfection. Saujani suggests that boys are socialized to jump off high dives and attempt daring tricks on the monkey bars, whereas girls are socialized to smile, look pretty, and be perfect by avoiding risks. Certainly, there are brave risk-taking girls who will grow up to become the Kamala Harrises or Katherine Johnsons of tomorrow, but the point is that studies show that risk-taking girls are the minority. To wit, a 2014 Harvard Business Review article, “Why Women Don’t Apply for Jobs Unless They’re 100% Qualified,” revealed a compelling statistic that was obtained from a Hewlett Packard internal report. It showed that men inside Hewlett Packard applied for a job when they meet only 60% of the qualifications, but women applied only if they meet 100% of the prerequisites.

Some argue that girls just need to be brave and show up in STEM classes. In February 2016, Reshma Saujani, founder of Girls Who Code, gave a compelling Ted Talk titled “Teach Girls Bravery, Not Perfection.” She proposes that girls need to learn to be brave, to take risks, to shed the shackles of perfection. Saujani suggests that boys are socialized to jump off high dives and attempt daring tricks on the monkey bars, whereas girls are socialized to smile, look pretty, and be perfect by avoiding risks. Certainly, there are brave risk-taking girls who will grow up to become the Kamala Harrises or Katherine Johnsons of tomorrow, but the point is that studies show that risk-taking girls are the minority. To wit, a 2014 Harvard Business Review article, “Why Women Don’t Apply for Jobs Unless They’re 100% Qualified,” revealed a compelling statistic that was obtained from a Hewlett Packard internal report. It showed that men inside Hewlett Packard applied for a job when they meet only 60% of the qualifications, but women applied only if they meet 100% of the prerequisites.

Nilanjana Dasgupta, a psychology researcher at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, was awarded over two million dollars by the National Science Foundation (June 2014–May 2021) to research the impact of gender on STEM aspirations. In her abstract, “Peer influences on adolescents' self-concept, achievement, and future aspirations in science and mathematics: Does student gender and race matter?” Dasgupta set out to research whether exposure to other females in STEM would influence a sense of belonging. In fact, Dasgupta has been studying how gender impacts girls’ and women’s participation in STEM for over a decade. In 2011, her team observed 100 male and female students in math class and found that female students who interacted with female peer-experts had a more positive attitude in their ability toward math. They also found that when girls had a woman teacher, the participation increased such that, “The percentage of female students who voluntarily answered questions in calculus class increased from 7% to 46% when they had a female professor, but decreased from 11% to 7% when they had a male professor over the course of a semester-long class.” No change was seen in the male students. Furthermore, the female students performed better than the male students regardless of the sex of the teacher; however the female students had more confidence when they had a female professor.

Dasgupta’s current research concludes that representation and belonging matter. She says, “Increasing young women’s exposure to successful female scientists, mathematicians, and engineers strengthens female students’ self-identification with STEM and enhances positive attitudes, feelings of self-efficacy, and motivation to pursue STEM majors and careers” and that, “For women and any other negatively stereotyped groups...belonging really determines whether you stick it out in a field that interests you. You feel a sense of camaraderie and comfort, or you start losing interest, confidence, and start thinking about leaving for another field.” Dasgupta recommends a “social vaccine” to keep girls in STEM classes. This stereotype inoculation means exposing girls from an early age to female STEM mentors, peers, teachers, and successful STEM women.

Bringing in women STEM representation and/or establishing girl-centric STEM mentor programs might be challenging for some communities to ramp up. However, books can be accessed now — today — right away, and girl-focused STEM-books have the enormous power to artificially increase representation in a meaningful way. Books can put positive female STEM representation directly in front of readers, and brain science conclusively supports that contact through “story” is not inconsequential.

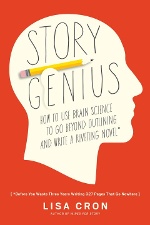

Lisa Cron, the author of two books rooted in brain science and story, says in Story Genius: How to Use Brain Science to Go Beyond Outlining and Write a Riveting Novel: “When we’re under the spell of a compelling story, we undergo internal changes along with the protagonist, and her insights become part of the way we, too, see the world. Stories instill meaning directly into our belief system the same way experience does — not by telling us what is right, but by allowing us to feel it ourselves.” She goes on to say, “When we’re lost in a novel, the protagonist’s internal struggle becomes ours, as do his hard-won truths. This is not a metaphor, but a fact…functional MRI (fMRI) studies reveal that when we’re reading a story, our brain activity isn’t that of an observer, but of a participant.” Therefore, a girl who reads about other girls succeeding in STEM is a girl whose brain chemistry is telling her she is there, she is having a successful STEM experience, and she belongs. This type of shift is not just about having a better attitude, but one that involves physical brain changes and connections.

Lisa Cron, the author of two books rooted in brain science and story, says in Story Genius: How to Use Brain Science to Go Beyond Outlining and Write a Riveting Novel: “When we’re under the spell of a compelling story, we undergo internal changes along with the protagonist, and her insights become part of the way we, too, see the world. Stories instill meaning directly into our belief system the same way experience does — not by telling us what is right, but by allowing us to feel it ourselves.” She goes on to say, “When we’re lost in a novel, the protagonist’s internal struggle becomes ours, as do his hard-won truths. This is not a metaphor, but a fact…functional MRI (fMRI) studies reveal that when we’re reading a story, our brain activity isn’t that of an observer, but of a participant.” Therefore, a girl who reads about other girls succeeding in STEM is a girl whose brain chemistry is telling her she is there, she is having a successful STEM experience, and she belongs. This type of shift is not just about having a better attitude, but one that involves physical brain changes and connections.

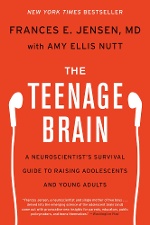

The term “plasticity” refers to a brain’s ability to structurally change and develop new neuronal connectors by thought and experience. Nobel Prize–winning psychiatrist Eric Kandel found that even as a snail learns, its brain structure and synapses change. Dr. Frances E. Jensen, a professor and chair of the department of neurology at the Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, says that children are imprintable and that, “Thinking, planning, learning, acting — all influence the brain’s physical structure and functional organization, according to the theory of neuroplasticity.” In her book The Teenage Brain: A Neuroscientist's Survival Guide to Raising Adolescents and Young Adults Jensen says, “Childhood and teen brains are ‘impressionable,’ and for good reason, too. Just as baby chicks can imprint on the mother hen, human children and teens can ‘imprint’ on experiences they have, and these can influence what they choose to do as adults.” She also says, “Brains are shaped — landscaped if you will — by the individual’s particular experiences.” The information children receive when reading a book shapes their very moldable young brains.

The term “plasticity” refers to a brain’s ability to structurally change and develop new neuronal connectors by thought and experience. Nobel Prize–winning psychiatrist Eric Kandel found that even as a snail learns, its brain structure and synapses change. Dr. Frances E. Jensen, a professor and chair of the department of neurology at the Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, says that children are imprintable and that, “Thinking, planning, learning, acting — all influence the brain’s physical structure and functional organization, according to the theory of neuroplasticity.” In her book The Teenage Brain: A Neuroscientist's Survival Guide to Raising Adolescents and Young Adults Jensen says, “Childhood and teen brains are ‘impressionable,’ and for good reason, too. Just as baby chicks can imprint on the mother hen, human children and teens can ‘imprint’ on experiences they have, and these can influence what they choose to do as adults.” She also says, “Brains are shaped — landscaped if you will — by the individual’s particular experiences.” The information children receive when reading a book shapes their very moldable young brains.

In review of the metaphorical math, fMRI technology shows that a person reading a book experiences the story as the protagonist. Add to that the neuroscience that supports that the experiences the brain receives shapes the landscape of thought. The sum equals a simple fact: Female STEM-positive books are bound to be powerful tools to provide a social inoculation to the future of girls and women in STEM. Dr. Jensen describes developing and ensuring a brain pathway as etching out a new ski run — powdery and without grooves at first, but after you make that same run over and over again it becomes carved and shaped, and it starts to feel sure and familiar. But that path needs repeating to take hold — the skier must venture it over and over to achieve its sureness. All this to say that children and teens are imprintable, but they need a regular diet of positive representation of girls and women in STEM, and books are an easy access point.

However, encyclopedia-type “here’s how you can learn STEM” stories shouldn’t simply be dumped into a child’s open hands. Ideally, books must be curated. At writing conferences, it is regularly drilled into writers’ heads that kids don’t pick up a book to be preached to; they open a book to be entertained. Three books that model girl STEM characters in a positive and entertaining way are: picture book Ada Twist, Scientist, middle-grade novel Emmy in the Key of Code, and young adult novel You Should See Me in a Crown — three completely different books all rooted in providing entertaining stories.

However, encyclopedia-type “here’s how you can learn STEM” stories shouldn’t simply be dumped into a child’s open hands. Ideally, books must be curated. At writing conferences, it is regularly drilled into writers’ heads that kids don’t pick up a book to be preached to; they open a book to be entertained. Three books that model girl STEM characters in a positive and entertaining way are: picture book Ada Twist, Scientist, middle-grade novel Emmy in the Key of Code, and young adult novel You Should See Me in a Crown — three completely different books all rooted in providing entertaining stories.

Ada Twist, Scientist by Andrea Beaty, illustrated by David Roberts, is a fictional picture book inspired by scientists Ada Lovelace and Marie Curie. Sure, this book features a girl STEM protagonist, but what makes it an effective story rests with the enjoyable page-turns, the story question, and the poetry elements of rhyme, rhythm, alliteration, anaphora, and assonance, not to mention the entertaining language choices.

Emmy in the Key of Code by Aimee Lucido features a twelve-year-old protagonist who draws readers in with her engaging voice, with the dilemma of being the new kid in town, and possibly with “the wrong note.” The author crafts text that causes us to worry about and root for the protagonist. Furthermore, middle graders who learn coding in school might be entertained by the fresh structure of seeing clever bits of code at the opening of each chapter. While the entertainment is happening, readers receive a few doses of social inoculation — Emmy learns how to code from a successful female STEM teacher (representation), and the story has an important subplot of Emmy discovering how to navigate a boy’s stereotyping belief that girls do not belong in STEM. Because readers are invested in Emmy, they experience the injustice of this prejudice alongside her (remember, fMRI technology has proven this). Emmy in the Key of Code carves out a safe space for children to believe that girls belong in the technology sector, thereby serving as a “mirror” (to paraphrase Dr. Rudine Sims Bishop) showing that girls have a rightful place in STEM.

You Should See Me in a Crown by Leah Johnson features high school senior Liz Lightly who sets out to win a scholarship for college because she would like to “become a hematologist and work with sickle-cell patients like [her] mom and [her] little brother.” This story is entertaining and never didactic, and it is accessible to readers whether they care about STEM or not (because on the surface it is not STEM-centered). It is about a contemporary girl who deals with wants, stakes, crushes, friendships, sexual identity, high school drama, and the unlikely chance at winning prom queen — and all this goes down while the character just so happens to like STEM, too, thus normalizing this interest.

You Should See Me in a Crown by Leah Johnson features high school senior Liz Lightly who sets out to win a scholarship for college because she would like to “become a hematologist and work with sickle-cell patients like [her] mom and [her] little brother.” This story is entertaining and never didactic, and it is accessible to readers whether they care about STEM or not (because on the surface it is not STEM-centered). It is about a contemporary girl who deals with wants, stakes, crushes, friendships, sexual identity, high school drama, and the unlikely chance at winning prom queen — and all this goes down while the character just so happens to like STEM, too, thus normalizing this interest.

Here are additional fiction and nonfiction books that model positive female STEM representation in a way that might capture a reader’s imagination. These books either highlight a STEM character and her achievements; or they are written by STEM authors or illustrated by a STEM illustrator; or they feature a girl protagonist who enjoys STEM as a normalized (rather than exoticized) part of her life:

Picture Books:

Counting on Katherine: How Katherine Johnson Saved Apollo 13 by Helaine Becker, illustrated by Dow Phumiruk.

Maya Lin by Jeanne Walker Harvey, illustrated by Dow Phumiruk.

The Secret Code Inside You: All About Your DNA by Rajani LaRocca, illustrated by Steven Salerno.

Me, Jane by Patrick McDonnell.

Joan Procter, Dragon Doctor: The Woman Who Loved Reptiles by Patricia Valdez, illustrated by Felicita Sala.

Middle Grade Books:

The Serpent’s Secret (Kiranmala and the Kingdom Beyond #1) by Sayantani Dasgupta.

We Dream of Space by Erin Entrada Kelly.

The Miscalculations of Lightning Girl by Stacy McAnulty.

Chirp by Kate Messner.

The House That Lou Built by Mae Respicio.

All Thirteen: The Incredible Cave Rescue of the Thai Boys’ Soccer Team by Christina Soontornvat *note: though this incredibly riveting nonfiction book features an all-boys soccer team, it is recommended because of this author’s engineering and science background that she is able to unpack the details for the readers in such a clear manner.

The 11:11 Wish by Kim Tomsic.

Young Adult Books:

Flying Free: My Victory Over Fear to Become the First Latina Pilot on the US Aerobatic Team by Cecilia Aragon.

Girl Code: Gaming, Going Viral, and Getting It Done by Andrea Gonzales.

Flygirl by Sherri L. Smith.

Code Name Verity by Elizabeth Wein.

For more book recommendations, see the Guide/Reviews Database subject searches Women--Scientists and Women--Engineers; and don't miss Christine Taylor-Butler's November/December 2021 Horn Book Magazine article "When Failure Is Not an Option: Connecting the Dots with STEM."

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!