The Writer's Page: Freedom Braids: The Power of Metaphors in "Liberation Literature"

Children are highly attuned to human emotions, curiously observant, and intuitively responsive to their environments. They begin to form ideas of fairness in early childhood. While they don’t yet understand all the complexities of the world, children are more aware than adults realize and could actually benefit from learning the hard truths that they are often shielded from. Of all the hard truths throughout history, slavery is surely among the hardest. Helping children understand its enduring institutional oppressions, including the violation of the human rights of millions, is daunting. How do you tell the truth about slavery to young children?

Children are highly attuned to human emotions, curiously observant, and intuitively responsive to their environments. They begin to form ideas of fairness in early childhood. While they don’t yet understand all the complexities of the world, children are more aware than adults realize and could actually benefit from learning the hard truths that they are often shielded from. Of all the hard truths throughout history, slavery is surely among the hardest. Helping children understand its enduring institutional oppressions, including the violation of the human rights of millions, is daunting. How do you tell the truth about slavery to young children?

I grappled with this question as I conceived the idea for my picture book Freedom Braids, which was illustrated by Oboh Moses. After learning that traditional African hairstyles served as “maps” that helped to free enslaved people in Colombia, I was inspired to write a story of an enslaved girl who learns braiding techniques that liberate herself and others. While traditional African hairstyles were always a tool for communication across the continent, signifying a person’s age, marital status, wealth, kinship, and/or religion, these intricate patterns also became secret codes that led to liberation during enslavement.

I grappled with this question as I conceived the idea for my picture book Freedom Braids, which was illustrated by Oboh Moses. After learning that traditional African hairstyles served as “maps” that helped to free enslaved people in Colombia, I was inspired to write a story of an enslaved girl who learns braiding techniques that liberate herself and others. While traditional African hairstyles were always a tool for communication across the continent, signifying a person’s age, marital status, wealth, kinship, and/or religion, these intricate patterns also became secret codes that led to liberation during enslavement.

I couldn’t begin to imagine the conditions of slavery, let alone fathom how it would feel to risk one’s life to try to escape it. Yet, I knew I had to write this story, especially for children. Growing up, I was enamored with stories — stories about my family, and about other people and places. As a Black child, when I couldn’t find the stories that reflected images and experiences of Black people in children’s literature, I read Black magazines, encyclopedias, and history books. Learning about cultures in Africa as well as the enslavement of its people was crucial to understanding a significant part of a shared history and identity. It served as a reminder of the collective strength and perseverance of my ancestors, and it allowed me to notice patterns and connect the cultural dots to another place and time, prompting me to embrace my culture and history with fervor.

When I wrote Freedom Braids, I revisited a story from my childhood. It took me decades to realize fully the magnitude of this work’s impact on my life and now my writing. Virginia Hamilton’s The People Could Fly: American Black Folktales, illustrated by Leo and Diane Dillon, freed my mind to conceive of a world where suffering Black people could reclaim their power and magic to help liberate themselves. After reading a reissue of her award-winning American Black folktale collection during a picture book intensive course in my MFA program at the Vermont College of Fine Arts, I realized the significance of metaphors in what the late author described as her “liberation literature.” Metaphors create lasting sensory impressions that help us understand or attempt to fathom circumstances that are enigmatic or beyond our experiences. They direct us toward the truth by evoking subtext or an implied, unspoken meaning. With elements of fantasy and folklore, metaphors played a powerful role in The People Could Fly. Based on tales of flying Africans and enslaved people that have been passed down through generations, the story begins with a description of some people from Africa who possessed the ability to fly. While “they flew like blackbirds over the fields,” many of them were captured and enslaved:

The ones that could fly,

shed their wings.

They couldn’t take their wings

across the water on the slave ships.

The blackbirds who shed their wings represent the Africans being enslaved with an implied message that African people were beautiful, brilliant, and distinguished before they were stripped of their freedom — their wings. By focusing readers’ attention on the majesty of the people who could fly but lost their ability when they became enslaved, the story highlights an important truth that is often neglected in narratives about slavery. It also sets the stage for when they use their brilliance and ingenuity to liberate themselves later in the story when an enslaved man named Toby knows the magic words that will remind the other enslaved people how to fly again. He shares the message with them, and they, too, fly away.

After rereading The People Could Fly as an adult, I took notice of the power of metaphors in other children’s books about slavery. In Never Forgotten by Patricia C. McKissack, also illustrated by the Dillons, a young boy named Musafa is kidnapped from West Africa and sold into slavery. Unable to move on, his father mourns and searches for answers. Mother elements — Earth, Fire, Water, and Wind — take turns following the boy during his capture and enslavement, and report back to the father. Water describes the ship that took the children:

A two-hundred-ton brig bound for a western shore.

Its belly bulged with children snatched

From Mother Africa’s arms…

Death was the captain of that ship;

Suffering, an apt first mate;

Cruelty the crew.

While the bulging belly represents the ship carrying people away, this could be interpreted as a metaphor for the greed for wealth and power. The captors enslaved so many African people that the ship could barely hold them. The descriptions of death, suffering, and cruelty as crew members directing the ship could be a metaphor for the demise of cultures, languages, freedom — life.

Mumbet’s Declaration of Independence by Gretchen Woelfle, illustrated by Alix Delinois, is a picture-book biography of an enslaved woman who brought a lawsuit against her owners to gain her freedom. In this story, Mumbet describes a mountain, which may be a metaphor for strength in the midst of harsh conditions. “Look at that mountain out there. Rain and wind, ice and snow try to wear it down, but there it stands, strong and rugged.” Like the mountain, Mumbet withstands the cruel realities of slavery. However, more than being just sheer strength, the mountain may be interpreted by another reader as a symbol of resistance or a stronghold against a threat. The writer may have intended to convey a deep sense of resilience and the ability to persevere in the face of adversity.

Well-crafted metaphors encourage young readers to think deeply and explore multiple layers of meaning. How readers interpret a metaphor is as important as the writer’s intentions.

In Freedom Braids, my own example of “liberation literature,” I used metaphors to signify sacred cultural traditions, ingenuity, perseverance, and hope:

Gather the midnight strands

tend the roots that gave you life

weave hopes into pathways —

paths that lead you home.

While the midnight strands may literally translate to hair, they also represent the women who gathered every night to braid. Tending the roots is a metaphor for keeping these sacred traditions alive. Weaving hopes into pathways — paths that lead you home — highlights the magnitude of these rituals. These woven dreams, these sacred traditions, liberated enslaved people. Snatched from their homeland, they were able to return to some semblance of home through their native customs. This lyrical verse is a reminder to always keep home with you.

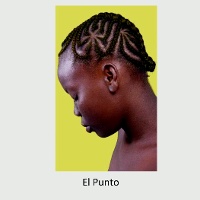

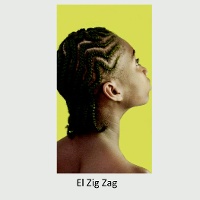

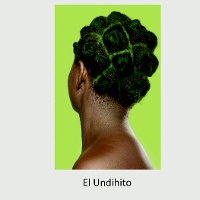

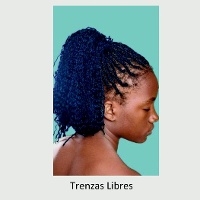

| Left to right: "El Punto" indicated routes that lead to a desired meeting point. "El Zig Zag represented paths; a river was shown with a similar winding shape. "El Undihito" was a style that women wore to conceal seeds that would later be used to cultivate the land. "Trenzas Libres" were loose braids that emerged as a symbol of joy for obtaining freedom. Photos: Adriana Cassiani, The ASALI Project. |

Children’s literature is a unique vehicle for exploring historical content and representing diverse experiences. Stories can inspire, motivate, engage, and enlighten us, and help us see our shared humanity. They reflect our experiences and identities, strengthen and challenge ideas, and help shape perspectives of one another and the world.

Slavery was an extremely dark period that can be quite challenging to teach. While adults may want to protect children’s innocence, shielding them from the truth prevents them from learning how to navigate different experiences. Done well, books help explore honest conversations with our youngest members of society. By creating lasting sensory impressions, metaphors evoke subtext that help “tell the truth” about the darkness of slavery in picture books. Drawing light from the dark, they create beauty out of tribulation, glean wisdom deep-rooted in tradition, and deepen an understanding of the world that encourages children to see themselves and others with greater compassion.

From the September/October 2025 issue of The Horn Book Magazine.

Single copies of this issue are available for $15.00 including postage and may be ordered from:

Horn Book Magazine Customer Service

magazinesupport@mediasourceinc.com

Full subscription information is here.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!