The Writer's Page: Hello Again

Writing sequels or companion books to my novels has never been tempting to me, probably because I like to think each book accomplished all I’d intended to say.

Writing sequels or companion books to my novels has never been tempting to me, probably because I like to think each book accomplished all I’d intended to say.

Writing sequels or companion books to my novels has never been tempting to me, probably because I like to think each book accomplished all I’d intended to say.

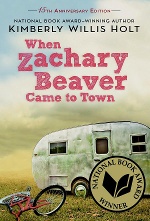

After completing When Zachary Beaver Came to Town (1999), I felt satisfied that I’d finished the story of Toby, Cal, and Zachary. When Zachary headed out of Antler, Texas, in his sideshow trailer, I, too, believed what Toby Wilson said: “We’d seen the last of him. I can’t tell you why. I just know.” What I wasn’t prepared for was twenty years of students asking if there would be a follow-up novel.

“No,” I’d say. “I doubt it.”

“But what happened to Zachary?” they’d ask.

I always answered with a question: “What do you think happened to him?”

Some students groaned. Others shared their ideas. Whatever they offered up, I told them, “Then that’s what happened. Your right as a reader is to take the story wherever you want when you turn the last page of a book.” That never seemed to satisfy them.

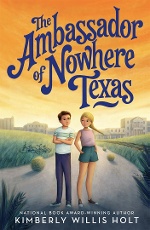

My readers’ urging for a follow-up was not the motivation for my return to Antler. Any idea I pursue has to be well-loved early on, or else I’d never endure the many drafts my work requires. The inspiration for the companion novel, The Ambassador of Nowhere Texas, came down to two words: marriage and math. A few years ago, while dusting off my bookshelves, I started thinking about Toby. Whatever happened to him? Whom would he have married? The answer came to me instantly — Tara, the bratty little sister of Toby’s childhood crush, Scarlett. The irony of that pairing caused me to laugh aloud. What kind of child would come of their union?

My readers’ urging for a follow-up was not the motivation for my return to Antler. Any idea I pursue has to be well-loved early on, or else I’d never endure the many drafts my work requires. The inspiration for the companion novel, The Ambassador of Nowhere Texas, came down to two words: marriage and math. A few years ago, while dusting off my bookshelves, I started thinking about Toby. Whatever happened to him? Whom would he have married? The answer came to me instantly — Tara, the bratty little sister of Toby’s childhood crush, Scarlett. The irony of that pairing caused me to laugh aloud. What kind of child would come of their union?

The next day, that question led me to brainstorming in a notebook. After abandoning the idea of a story about Toby’s and Cal’s sons being best friends (the same setup as in Zachary Beaver), I realized that if I wanted to write a fresh story, the main character would need to be Toby’s daughter. And maybe Cal wouldn’t have children. I did the math, trying to figure out a realistic time period for Toby and Tara to have a twelve-year-old. The answer — 2001. That year would place the new book three decades after sideshow boy Zachary Beaver had visited Antler. More importantly, setting it then opened up the possibility of writing a post–9/11 story, showing the event’s impact on a small Texas community, similarly to how the Vietnam War threaded through When Zachary Beaver Came to Town.

Reuniting with old characters comes with some responsibilities. With the exception of reading excerpts to audiences, I had not reread Zachary Beaver in almost two decades. After I committed to writing the new book, I opened Zachary Beaver at page one, read, and underlined like a student enrolled in a required class. Thank goodness I did, because I had remembered some things incorrectly. I thought Cal lived across the street, not next door. How had I forgotten about Sheriff Levi’s eye twitch? Or the name of the school mascot? Meeting up with old characters was fun and gave me a chance to sprinkle some familiar details into The Ambassador of Nowhere Texas.

Sometimes secondary characters have more to offer after the original story ends. Miss Myrtie Mae played a small but important role in When Zachary Beaver Came to Town, with the way she accepts others’ dreams and claims and records the significance of small-town life in her photography. When I started to write the companion novel, I realized I wasn’t done showing her sense of fairness and belief in using one’s gifts. Even though she has passed on before Ambassador begins, she remains a crucial part of the tale. Her impact on the story parallels that of Cal’s brother, Wayne, who serves in the Vietnam War in Zachary Beaver. Although Wayne is never “on stage,” like Miss Myrtie Mae’s photos his letters are reminders of small-town life’s virtues.

Merging the old with the new wasn’t always that easy. In my early drafts, I reintroduced Zachary but kept him at a distance. Something didn’t seem right, though. Then I realized I was like my young readers who wanted to know what happened to Zachary when he left Antler. And I needed to see him up close. Instead of being a convenient subplot, the search for Zachary became the spine of the story, fusing protagonist Rylee’s friendship with newcomer Joe, and Toby and Cal’s reunion with their old friend. Like a sudden gust of wind changing a tumbleweed’s course, that revelation redirected the story and gave The Ambassador of Nowhere Texas a stronger connection to Zachary Beaver.

One of my own mental blocks in writing Ambassador had to do with geography. A back road I hadn’t traveled down for years was a crucial part of the story, and it was fading in my mind’s eye. A return trip to the Texas Panhandle, my home for nineteen years, and driving on that road conquered the limitations that my faulty memory was causing my work. An added bonus was that it contributed to more texture in additional scenes, including the book’s closing paragraphs.

While writing early drafts of The Ambassador of Nowhere Texas, I had to constantly remind myself that although Toby, Cal, and Zachary’s friendship weaves through the new book, the story belonged to Rylee. She had to steer the plot. When I finally gathered the courage to focus on her, the story found its legs. My wish is that readers appreciate Ambassador as a standalone book that affectionately nods to Zachary Beaver. The two stories may share common ground about acceptance and the value of friendships, old and new, but they are unique in their unfolding of those truths.

Although it probably would have served me better, I wouldn’t have been able to write a companion novel to Zachary Beaver any sooner. The almost two decades that had elapsed gave me a perspective on the former story I couldn’t have had earlier. I was able to see how kids coming of age during the 1970s in a tiny Texas town weren’t so different from kids thirty years later or, for that matter, today. Despite technological advances and different world events, young people are still searching inside themselves, questioning who they are and who they want to be. Rereading the story, almost forgetting I had written it, helped me see this clearly. Perhaps the years between companion books can contribute more to the writing than we realize.

Sequels and companion books can be rewarding and risky for writers. True, they are usually books that have a built-in readership by way of the original story. However, they come with heavier expectations, not only to satisfy readers with a new story but also to do justice to the old one. Because of that, most writers who step in that direction don’t do so lightly or without serious consideration. If they do commit to making the journey, it’s not without peril or joy. The two are constant traveling companions. Hopefully, for both writer and reader, it turns out to be a gratifying trip.

Other Return Visits

From the March/April 2021 issue of The Horn Book Magazine.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

As I did with Miss Myrtie Mae, Virginia Euwer Wolff also felt an alliance with a secondary character, such that it caused her to write a companion novel to her best-known work many years later. She says, “When Jolly (in Make Lemonade, 1993) had first come to me, I’d had no idea of her source, and had merely plunked her down on the page as someone to be pitied, scorned, maybe eventually embraced. I wrote book number two, True Believer (2001), as a placeholder, while I avoided the hardest task of all: finding Jolly’s beginnings.”

As I did with Miss Myrtie Mae, Virginia Euwer Wolff also felt an alliance with a secondary character, such that it caused her to write a companion novel to her best-known work many years later. She says, “When Jolly (in Make Lemonade, 1993) had first come to me, I’d had no idea of her source, and had merely plunked her down on the page as someone to be pitied, scorned, maybe eventually embraced. I wrote book number two, True Believer (2001), as a placeholder, while I avoided the hardest task of all: finding Jolly’s beginnings.”

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!