The Writer's Page: Imagining Our Way to the Other Side: Children's Literature and Radical Imagination

In a 2020 essay called “The Pandemic Is a Portal,” novelist and activist Arundhati Roy wrote,

Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew. This one is no different. It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next. We can choose to walk through it, dragging the carcasses of our prejudice and hatred, our avarice…Or we can walk through lightly, with little luggage, ready to imagine another world. And ready to fight for it.

In a 2020 essay called “The Pandemic Is a Portal,” novelist and activist Arundhati Roy wrote,

Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew. This one is no different. It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next. We can choose to walk through it, dragging the carcasses of our prejudice and hatred, our avarice…Or we can walk through lightly, with little luggage, ready to imagine another world. And ready to fight for it.

But what are the tools that will help us imagine a future beyond the COVID-19 pandemic, beyond the racialized divisions threatening to tear our very society apart? Among the other liberatory theories and practices at our disposal, there is a critical role for an unexpected revolutionary force: children’s literature. While parents and caregivers may have looked to stories to help their children escape stress during the pandemic, enjoyably occupy their time at home, or keep up their reading skills, the fact is that children’s literature in general, and children’s fantasy and speculative fiction specifically, do the important work of building not just young people’s imaginations but their radical imaginations.

Children’s books have always been roadmaps to the future and blueprints for tomorrow, because it is in their pages that young people have received the tools and the imaginative practice to envision what they want their worlds to look like. And if there’s any time in history that this future planning is critically in need of radical imagination, it is now. If in the post-COVID world we humans are to recalibrate our relationship to the environment and toward our economic, social, and political systems, that means our future leaders, teachers, artists, and politicians — our future adults — need to imagine radical possibilities for the world. They must enact a sort of radical empathy, a radical love toward those both like and unlike themselves. Children’s fantasy and speculative fiction have the responsibility and the power to do that critical work. To put a finer point on it: a particular type of young people’s fiction can do this work, because not all fantasy is created alike.

Consider the great English fantasists and Oxford professors Lewis Carroll, C. S. Lewis, and J. R. R. Tolkien. Their beloved works, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass, the Chronicles of Narnia, and The Lord of the Rings, are beautiful stories of enchantment and absurdity, even as the authors infused their academic work (as well as their often-reactionary politics) into their stories. Indeed, as Maria Sachiko Cesire, author of Re-Enchanted: The Rise of Children’s Fantasy Literature in the Twentieth Century, notes, the children’s literature of the “Oxford School” can be understood as an “empire of the mind,” a space to (as she put it in an interview with Slate) “re-inscrib[e]…colonialist actions and privileges” even as the power of the British empire was waning.

What I am talking about is something different from thinly masked colonialist fantasies writ onto the bodies of elves and hobbits. (As a side note: I am actually a Tolkien fan, but it’s important to be able to critique your favorites with clear eyes.) What I am talking about, rather, is what activist and writer Walidah Imarisha terms “visionary fiction”; that is, “fantastical writing that helps us imagine new just worlds…fantastical literature that helps us to understand existing power dynamics, and helps us imagine paths to creating more just futures.” I am talking about the writings of Nnedi Okorafor, Ellen Oh, Carlos Hernandez, Kwame Mbalia, and Tracey Baptiste (to name only a few favorite authors writing this sort of children’s literature). Visionary fantasists can help us imagine worlds beyond racial discrimination, or homophobia, or war. But before we can bring those realities into being, we must be able to dream them. As Imarisha asserts, “Any time we try to envision a different world — without poverty, prisons, capitalism, war — we are engaging in science fiction. When we can dream those realities together, that’s when we can begin to build them right here and now.”

* * *

When I wrote my Kiranmala and the Kingdom Beyond trilogy (The Serpent’s Secret, Game of Stars, and The Chaos Curse) I was inspired by my grandmother’s Bengali folktales as well as novelist Toni Morrison’s admonition, “If there is a book that you want to read and it hasn’t been written yet, then you must write it.” Growing up as a brown-skinned Indian immigrant daughter in the heart of the American Midwest, I rarely saw myself represented in the stories around me. If my community was represented, it was with violence, mockery, and derision. And the truth is, narrative erasure is a kind of psychic violence. After years of not seeing myself represented positively in books, television programs, and movies, a part of me began to believe, deep down, that maybe I wasn’t worthy of representation; that maybe I couldn’t be the hero, even of my own story.

In addition to the neglect afforded by childhood cultural invisibility in books and media was the experience of venomous, purposeful cultural erasure. From almost daily racist microaggressions (like kids in the schoolyard who rubbed at my skin to see if my “tan” would come off) to macroaggressions (like tar in our family mailbox) when I was a child, I got the message loud and clear that I — who had been born in the U.S. — would be a perpetual foreigner, that my family and my community had no place in the story that mainstream America insisted on telling about itself.

Four generations of the author's family with her maternal grandfather (front row) in 2013. (Photo: Subin Das.)

Luckily, I had a model of resistance at home: activist parents who helped me name my monsters. While my character of Kiranmala fights long-toothed, sharp-clawed, carnivorous monsters called rakkhosh, my personal rakkhosh was racism. It wasn’t until I learned to recognize this monster as something systemic, and not something that was inherently wrong with me or my community, that I could defeat its psychic hold over me. I wrote the Kiranmala stories so that my children, and all children, could see themselves as important enough to star in their own story, strong enough to be the hero, powerful enough to save the multiverse.

Beyond folktales, the Kiranmala series also relies heavily on string or multiverse theory — the idea of parallel universes that exist near one another but are unaware of one another’s existences. This seemed a perfect metaphor for the immigrant experience. Being able to straddle multiple worlds, code-switch among multiple languages and cultures, is a kind of a superpower. Indeed, celebrating this kind of borderless identity gives young readers an imaginative antidote to the rabid nationalism we have seen infecting the U.S. during the pandemic. To see immigrants as dimension hoppers, galaxy walkers, and space explorers, to read a story where being from an immigrant family is to be a superhero, is a profoundly political act, particularly at this time.

* * *

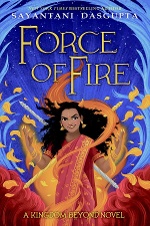

But representation and metaphor aren’t enough in and of themselves; what I’ve come to realize is that we need a joyous revolution. My most recent middle-grade fantasy, Force of Fire, is the story of the fire rakkhoshi Pinki, a descendant of revolutionaries, who is struggling with how best to live up to this heritage. Initially, Pinki wants nothing to do with rebellions or do-goodery; rather, she just wants to learn how to tame her seemingly out-of-control fire power. When, however, the son of her country’s Serpentine Governor-General offers her a secret deal to do just that, she finds herself becoming a reluctant leader of her country’s freedom struggles against the Empire of Serpent Overlords. Force of Fire is about a young woman finding and celebrating her voice, her language, her strength, rather than being afraid of them. As the Rabindranath Tagore song to which Pinki returns throughout the story says, “If there is no light, if the path before you rages with dark, then light your own heart on fire. Be the beacon. Be the spark.”

But representation and metaphor aren’t enough in and of themselves; what I’ve come to realize is that we need a joyous revolution. My most recent middle-grade fantasy, Force of Fire, is the story of the fire rakkhoshi Pinki, a descendant of revolutionaries, who is struggling with how best to live up to this heritage. Initially, Pinki wants nothing to do with rebellions or do-goodery; rather, she just wants to learn how to tame her seemingly out-of-control fire power. When, however, the son of her country’s Serpentine Governor-General offers her a secret deal to do just that, she finds herself becoming a reluctant leader of her country’s freedom struggles against the Empire of Serpent Overlords. Force of Fire is about a young woman finding and celebrating her voice, her language, her strength, rather than being afraid of them. As the Rabindranath Tagore song to which Pinki returns throughout the story says, “If there is no light, if the path before you rages with dark, then light your own heart on fire. Be the beacon. Be the spark.”

Force of Fire is based on not just my grandmother’s Bengali folktales but also on the real-life stories I grew up hearing of my revolutionary ancestors in India. Because I, too, like Pinki, am descended from revolutionaries. Among the many freedom fighters in my family who fought against the British occupation of India was my maternal grandfather, Sunil Kumar Das, who went to British prison at age fifteen for his revolutionary activities. Before he died in his nineties, one of India’s oldest recognized freedom fighters, he instilled in me a fierce, fiery opposition to any and all injustice, and a duty to fight for freedom in all its forms.

Sayantani's grandfather and uncle on India's first Independence Day. (Photo courtesy of the Das family.)

Force of Fire is inspired by not only my family’s anticolonialist history but language-oriented freedom struggles around the world, including the Bhasha Andolon (language revolution) in Bangladesh, and the language martyrs of that country who fought to maintain Bengali as their national language. It is even inspired by my own immigrant parents’ dedication to teach me Bengali, even as my elementary school teachers instructed them to speak only English to me (an order they did not, thankfully, follow). As a character says in Force of Fire, “Our mother language is the source of our strength…Destroying a people’s language, not letting children learn the ways of those who came before them, is the surest way to kill a culture.”

In reading visionary children’s fiction, our young people can see not only themselves but also people unlike themselves, and light their imaginations and hearts on fire with all the radical possibilities out there. In the safe space of a story, young readers can ask themselves what they would do in situations of injustice, how they would want to respond to challenges not unlike the ones in the world today. And through this moral and ethical and empathetic practice, they can grow into the best versions of themselves. They can be the beacons, they can be the spark — lighting all our ways through the portal of this pandemic, and into a brighter future.

From the September/October 2021 issue of The Horn Book Magazine.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!