Alexs Pate Talks with Roger

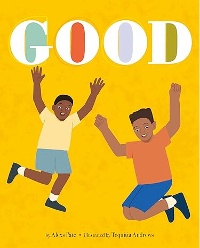

With his national teacher-training program, The Innocent Classroom, Alexs Pate explores a new paradigm for learning. Good, Pate’s picture book for young children (illustrated by Tequitia Andrews), puts that paradigm into action, providing reader-aloud and reader-along with an opportunity to co-discover Good.

Talks with Roger is a sponsored supplement to our free monthly e-newsletter, Notes from the Horn Book. To receive Notes, sign up here.

Sponsored by

With his national teacher-training program, The Innocent Classroom, Alexs Pate explores a new paradigm for learning. Good, Pate’s picture book for young children (illustrated by Tequitia Andrews), puts that paradigm into action, providing reader-aloud and reader-along with an opportunity to co-discover Good.

Roger Sutton: I’m curious to know what kind of a child reader you were.

Alexs Pate: Oh, I was a voracious reader. I’ve always said that my mom fed me books like candy. If I was headed to my bedroom there was always a book waiting for me at the door or on the bed. Always. I read Greek and Roman mythology. Black writers, European writers, Russian writers. I’ve been reading voraciously until just recently when I’ve slowed down a bit.

Alexs Pate: Oh, I was a voracious reader. I’ve always said that my mom fed me books like candy. If I was headed to my bedroom there was always a book waiting for me at the door or on the bed. Always. I read Greek and Roman mythology. Black writers, European writers, Russian writers. I’ve been reading voraciously until just recently when I’ve slowed down a bit.

RS: Why did you slow down?

AP: I think on some level being a writer has slowed me down as a reader because I’m constantly looking for time to get to my work. And because I think a lot of contemporary stories don’t intrigue me or capture my imagination as much as before. Stories were always so powerfully constructed, so rich and thick.

RS: No Hardy Boys for you, huh?

AP: I did Hardy Boys in the time of Hardy Boys. I haven’t written a novel in a while, but I’ve had two or three sitting in my computer while I was doing the Innocent Classroom thing, and I’m finishing up one that’s not a Hardy Boys, but kind of light. It’s a swashbuckler. I always wanted to write a story about pirates. So I’m doing that.

RS: Would this be for kids or for grownups?

AP: I’m not sure. I don’t know if it will ever get published, mainly because it is a book about pirates. But also because I’m not sure whether it’s middle grade or adult. Writers coming up now seem to know what the distinction is between juvenile, middle grade, adult. I don’t really know what the distinctions are. I mean, Good is obviously a children’s picture book, but everything else I write has always been for adults.

RS: What got you into children’s books in the first place?

AP: I think it was the work I was doing with Innocent Classroom and the belief that our children are not being given strong enough preparation for the challenges they face in the world. I’ve been mostly focused on internal development, on the support that we give ourselves and our children to deal with our own issues so that we are better able to face the issues outside. With Being You, my first picture book, it’s like “How do you choose your path? Where does information come from? How do you choose who you actually are? And how well can you live up to who you are?”

RS: Let’s talk about The Innocent Classroom.

AP: I’ve developed this idea that our children are gathering “guilt” over the course of their early lives. And that, by the time they go to school, they’re already weighed down with barriers that prevent them from building relationships with their teachers, their proper guides. And, assuming that a teacher’s ready for a child, that the child needs to also be ready to be taught. So in Innocent Classroom I talk about the guilt that we accumulate. And that guilt has to do with the impact of negative stereotypes that are cumulatively built inside us as people. One of the things that happened for me is I started to feel the weight of that guilt as a young man and as I moved up in age, it has you always looking over your shoulder, always assuming things are not going to go right, always assuming somebody is going to hurt you or inhibit you in some way. And so I started meditating on my own parcel of guilt that I was carrying around. “Where did it come from? Why do I feel this way? Why am I never comfortable? Why do I always flinch when a police car pulls up behind me if I’ve done nothing wrong? Why do all these things have such a significant impact on me and on my life?” I was writing an essay called “Revolutionary Innocence” about how I felt like the revolution needed to be internal, not external, at a time when most of the work, most of the effort and energy, was going into community stuff. I was talking about that with some foundation people at the end of a meeting, and there was a lot of interest. “What do you mean by guilt? What do you mean by innocence? What do you mean by freeing yourself from all of that weight? And how do you do that, and can it be done?” And I was in the middle of doing it. I was in the middle of meditating. In terms of identifying, inventorying the things I had that maybe I had not done well and clearing out all the stuff that I had taken on without thinking about it. So then, when somebody asked me, “Can you teach that?” I did. The first place I experimented with it was in Omaha, Nebraska. My first meeting was with like 150 teachers and I said, “I think I have something that will help you in the classroom, but you’ll have to come back and tell me about it.” And they came back and said, “Wow. This was a significant change in the way I interact with the children that I teach.” The goal there was to help educators help our students let go of that weight.

RS: Can you give me an example of something a teacher might do, or not do?

AP: There are big things, and there are little things.

RS: Give me a little thing.

AP: A teacher knows that children go to gym class and then they come back, and some of the girls would love to have a hairbrush, and so teachers started putting a brush on their desk. This is not about talking to kids. This is about doing things for them. It’s about knowing things about them. It’s about going to sporting events when a child is involved in sports. The child sees you there and knows that you care about them. That you care about them in a way that you’re out to change the way they interact with you. It’s hard to be nasty to an adult who is trying to care for you. Although it does happen.

RS: It happens.

AP: So on one hand I’m teaching teachers to be on the lookout for that cumulative impact of negative stereotypes. Children who are angry in the morning, 8 o’clock in the morning — what, why, how could you be so angry? Children who are sad, who are silent, who are fighters — I would translate that into: “I want to be seen. I want to be heard. I want to feel like somebody cares about me.” When that child fully understands how deep and authentic a teacher’s capacity to care about them is, their reciprocation of that is powerful. And so when educators began to feel that and see that that could happen, it changed everything. In some districts, there are “innocent schools” out there where principals have adopted the concept and challenged their teachers to break through those barriers, because it really is about how strong the relationship is between teacher and student.

RS: I started my career as a children’s librarian in Chicago, and I realized that a lot of the stuff I had internalized as a child about other children — basically, I was afraid of them — I was bringing into my adult work with children. And it didn’t belong there. What you’re doing here sounds like you’re saying the teachers need to change themselves in order to better interact with the children.

AP: Right, but the focus of the conversation is not about changing the teacher, it’s about having the teachers walk into the world of the child and then let the teacher respond to that moment through change and transformation within themselves. Because many teachers have never been embraced in the same way that I’m talking about them embracing their children. So, in some way it’s a moment of clarity for educators: “Oh, I remember what it was like.” I remember what it was like when my mom was sick and how that impacted my ability to be a good student, how it impacted my ability to express my curiosity. Our children are going through all kinds of dramatic, amazing, traumatic realities. And there was a period of time where we tried to stay completely away. Like “we’ll just teach you,” and I don’t think it’s served our children well. Understanding their experiences, the challenges they face. I’ll take it all the way to the point in the program, when teachers fully understand what I’m getting at is when I say, “When you reach a level of clarity in your relationship with a child and you look at them, what are they seeing? Reverse that position. When you’re most annoyed, when you’re most angry, when things are most seemingly unclear, what is that child seeing in your face? And begin to work backwards from there.

RS: That's pretty brilliant.

AP: Well, it works. I mean it’s difficult now given the funding realities and schools and all of that, but I feel like I was onto something and that it is and has been making a major impact on the way children and teachers interact.

RS: I know that a lot of your work has also been in antiracism. So what do we do about societal forces that are having an impact on both that child and that teacher?

AP: I was talking to a teacher colleague the other day and he was saying, “What do we do now? How do I go into the classroom now when they’re saying I can’t say certain words, I can’t do certain things?”

RS: Right. “Now that America is a freaking nightmare, what do I do?”

AP: I say the first thing you do is you remain unchanged internally. You have to fortify that energy that you have to make life better for the people around you and in the community you live in. The other thing is, as you get older, you realize these are cycles and that this will not last. This won’t last because that’s the way history works, and the way organisms evolve. The organism of American culture is changing. I knew twenty years ago that we were going to go through some very hard stretches related to race and culture. We’re deeply dug in. We’re scared. And so this is about holding on to a high standard of human interaction and not changing the core of who you are in the process. This is about maintaining your identity internally and looking for opportunities to express it out loud. And when that moment comes, to do that with the same kind of conviction that you would do it in every other case in your life. Nurture and develop the logicality and the philosophical core of where you’re coming from, what you believe in; hold onto that because people are waiting to hear that when the time is right. Myself, I went to Aristotle. At the core of Aristotelian philosophy is this idea that good is the thing for which all other things are done. So I teach teachers how to discover the good in themselves and thus see good in the children around them. I ask teachers, “What is going on in your world? Why are you a teacher? What drove you to that point? What was the good that generated that energy?” And I’m saying to you that the same thing is driving that child. That child who is angry has a good that is moving in. For some reason their instincts tell them the best way to respond to their own good is to be angry. Why is that? What is that good? Decipher that good, and when we do that, you inevitably get to the point where you’re like, “Oh, I see.” And then the question is, what strategies do you have to respond to that need? Whether it’s to be cared for, whether it’s to be seen, recognized — whether it’s to help that child feel like they belong in the classroom with you — whatever it is. So it can start in kindergarten, with having teachers just put a picture of a favorite character on their desk. No conversation about it. Eventually a child is going to ask, “Why do you have this character on your desk?”

RS: Captain Underpants on your desk.

AP: And if you hear a child talking about airplanes — build a model airplane and put it on your desk. It just changes everything. It changes the air and the energy between that educator and that child and allows for another step forward, so that the relationship gets to be built the way relationships are supposed to be built. I just believe that we are past the time when you can herd forty kids into a room and assume that they’re going to sit there and listen to you pontificate.

RS: So how do you then take what is really some complicated thinking and adapt it to children. In your picture books Good and Being You, you’re speaking directly to children. So what are you expecting these books to do with young children?

RS: So how do you then take what is really some complicated thinking and adapt it to children. In your picture books Good and Being You, you’re speaking directly to children. So what are you expecting these books to do with young children?

AP: Well, I'm imagining a parent reading this book to a child, and the parent's eyes are gleaming, at the same time the child is being engaged by the ideas and not as much the story. The story is in the images, and the illustrator has done their job and created an easy-to-see and -read progression of this story, but the progression of the story is a progression of the way I'm suggesting young children should begin to think. What I want is for a child to look up at their parents or to look around them and say, “Yeah, I didn’t do that right. I could do that better, and there’s something in me that wants that. I need to find that. I need to understand.” The hope here is that I can transfer this desire to manifest authentic qualities that I think are being lost in our families. That since there is hope and positivity in our daily small-scale lives, that will change the future. Somebody asked me—and maybe it’s the same question you're asking me now — “Why would I talk so directly to a child? Why wouldn’t I bury this in a story where you had to sort of suss it out?” I think some things need to be said plainly to our children. I just think we’re at that time, and especially among children of color, where the story is often about the character being up against some tragedy or trauma, but I didn't want to walk down that path. What I wanted our children to see is that within them already is the capacity to see good, to see positivity. To have, no matter what your circumstances are, a way to manifest the good.

RS: It doesn't seem to me like the pictures in Good are illustrating the text so much as they’re an example of, here’s one situation where you could apply this fairly abstract and poetic text. Was the story of the boys and the kite and the sailboat yours? Or was that the illustrator?

AP: That was the illustrator. I mean, it was a back-and-forth, but when I produced that text, I didn’t have an image in mind. For me, it was the idea. The text is completely bare; it is simply: “You are good. Within you is a good, and there are things that are going to happen that are going to darken that day, but you still have good in you and it will not abandon you, and if you embrace it there is a new possibility the next moment.” That’s it. And obviously I’m capable of building a story around it. But the idea here is, let’s clear away everything and say to that child who is problematic, who is traumatized, let’s just say to them, “There’s something in you that’s good and I’m going to help you find it. And we’re going to join hands and we’re going to go forward that way.”

RS: The book leaves a lot of room for dialogue between the caretaker and the child.

AP: Yes, and my part of it was designed that way. When I sat down with my editor, they said, “Okay, so what images are you imagining?” I’m like, “Uhhh.” I don’t know whether that’s bad; that’s probably terrible.

RS: Well, you’ve got to give the illustrator room to breathe, you know. It really is a collaboration in that way.

AP: I think she did a great job.

RS: I loved the bit at the end after the kite has fallen apart and you see the boat, which I’m assuming is made with a piece of the kite. And I think the reason it is as powerful as it is, is that it’s unspoken. That you don’t have you, Alexs, pointing. It exists on its own for kids to discover.

AP: Right. I was asked to contribute some notes to a teacher’s guide. I said, “Take the two boys and tell me what their good is, each one, separately. And how one good causes this to happen, or responds to the rain and the storm this way, and what does the other kid do? I mean, underneath all this, there is a story to be made. It’s happening, and it’s the way life works. Some children are capable of going off and saying. “Okay, I’ve got all this trash that I thought was a kite, I’m going to make a boat out of this. This is good.”

RS: Good.

AP: Exactly.

Sponsored by

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!