Lisa Yee Talks with Roger

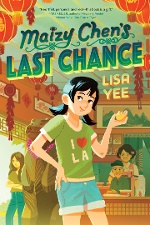

Last seen in this space chatting about Supergirl and Wonder Woman, Lisa Yee returns to talk about Maizy Chen’s Last Chance. Maizy was looking forward to the perfect LA summer; instead, her mother drags her to Last Chance, Minnesota, where Maizy's grandparents own a Chinese restaurant and from where her mother escaped long ago. Family dramedy, family history, and family secrets combine for a very different kind of novel from my old friend Lisa.

Talks with Roger is a sponsored supplement to our free monthly e-newsletter, Notes from the Horn Book. To receive Notes, sign up here.

Sponsored by

Last seen in this space chatting about Supergirl and Wonder Woman, Lisa Yee returns to talk about Maizy Chen’s Last Chance. Maizy was looking forward to the perfect LA summer; instead, her mother drags her to Last Chance, Minnesota, where Maizy's grandparents own a Chinese restaurant and from where her mother escaped long ago. Family dramedy, family history, and family secrets combine for a very different kind of novel from my old friend Lisa.

Roger Sutton: Where do you get your Chinese food?

Lisa Yee: I get it in Monterey Park, California. In America, Monterey Park is famous for Chinese food. My parents still live there, and that’s where I was born and raised. Every time I go to their house, they have a feast laid out for me with dim sum and roast duck and everything. I take more back with me to my little studio, and I continue eating it nonstop.

Lisa Yee: I get it in Monterey Park, California. In America, Monterey Park is famous for Chinese food. My parents still live there, and that’s where I was born and raised. Every time I go to their house, they have a feast laid out for me with dim sum and roast duck and everything. I take more back with me to my little studio, and I continue eating it nonstop.

RS: So, this is food that your parents have cooked?

LY: This is food that my parents have purchased by themselves.

RS: I see.

LY: Growing up, my mom didn’t cook Chinese food. My grandmother did, but my mother didn’t. She said there are so many ingredients and so many restaurants here, it’s easier to go out. I grew up on pork chops and meatloaf. The regular stuff.

RS: When I was at school out there, my favorite place for Chinese was the Panda Inn in Pasadena. Have you ever been there?

LY: Oh my god, yeah. I’ve been there. And now they also have Panda Express, so they’re everywhere.

RS: That’s them? I didn’t know that. I think there was just the one back then.

LY: Yeah, I’ve been there. It’s very fancy.

RS: Their hot burnt pork is the best. Of course, that’s what, forty years ago? Fifty?

LY: We’re not that old. Three years ago? Yeah.

RS: I have to confess my shallowness: when I started Maizy Chen, the first thing I thought of was Judith Krantz’s Dazzle. Have you read that?

LY: No. I’ve read some of her other books.

RS: The heroine is a celebrity portrait photographer who gets her start in food photography, so I learned all about food styling, Maizy’s mom’s job.

LY: I used to do a lot of food commercials, as a writer and producer, so I hung out with the food stylists, and I know about all the fakery.

RS: I remember when the Krantz novel came out, there was an outraged editorial in Gourmet, I think, saying they never employed such tricks as Judy divulged in her novel.

LY: Oh, it’s all fake. I love pointing this stuff out. If you go in the cereal aisle and you look at the boxes, that’s glue instead of milk. Sometimes if you look very carefully, you can see a little drop of glue on the side. Milk wouldn’t do that. You have to use the actual product itself, but for everything else, you fake it. And truth be told, people fake the actual product. I don’t know if you still have to do this, but back in the olden days, we had to sign things for the networks saying that everything was on the up-and-up.

RS: Well, I’m sure with you everything always was on the up-and-up.

LY: And it still is, Roger.

RS: Good. Yes. So, this is quite a different kind of book from you. The canvas is so much bigger. That’s the main difference I see. It’s still funny. It’s still got these great relatable kids in it. But there seemed to be more characters, as well as more time periods.

LY: Yes, that’s true. I’ve always done contemporary realistic fiction (aside from the DC superheroes). I thought about doing historical fiction before but set it aside. This ended up being a mash-up of the two. I always knew I wanted to tell Lucky Chen’s story, Maizy’s great-great-grandfather. The original draft presented his story as a graphic novel that she illustrated.

RS: Wow.

LY: I’ve wanted to do a graphic novel, too, but as much as I love that format, I realized after I had written it that it didn’t serve the story. With Maizy telling and illustrating it, the story was coming through her lens instead of through Opa’s, and he could get into more details. So, I rewrote the whole thing to what it is now.

RS: And I think you would really miss that wonderful bond that we get between Maizy and Opa.

LY: I loved writing their relationship, Opa especially. He’s just such a hoot. She didn’t know what to expect with him or with anybody, really, and then to find herself proven wrong was fun to write.

RS: And the characters are three-dimensional. I don’t feel that you’re trying to tell us something about this is how Chinese grandparents are, which is a trap some books fall into, using a character as an emblem for a culture.

LY: Oh, absolutely. It’s funny. Her grandparents have been in America for years. They’re not first-generation. They’re American; they happen to be Chinese. That’s what I write about with Maizy. Not just Maizy, but Millicent Min and my other books — their race just happens to be part of the fabric of who they are. It’s not a symbol — look at me, I’m Chinese, I represent everything Chinese. That’s not the case at all.

RS: When I was reading the grandparents’ names, Opa and Oma, I thought, that’s weird, maybe there’s some Chinese thing I don’t know about, and she’s going to tell me later.

LY: That came from my family background. My grandparents emigrated from China, and my grandmother really wanted everyone and everything to be American. When she had her kids, there was a German midwife. To my grandmother, the midwife looked white and white meant American to her, so she had the midwife name the kids. That’s why I have an uncle Otto and an auntie Verna and an auntie Harriet, and that’s why Lucky thinks the names for grandparents are Opa and Oma.

RS: There’s a lot of humor and family warmth in this book, but I sense that there’s some anger here that I haven’t experienced in your books before.

RS: There’s a lot of humor and family warmth in this book, but I sense that there’s some anger here that I haven’t experienced in your books before.

LY: I guess there is. There’s an undercurrent of anger and confusion, especially with the racist acts that take place. It’s something that Maizy is somewhat blissfully unaware of until she goes to Last Chance. The microaggressions start, and then there are the hate crimes, which she has never encountered before. When Opa tells her about Lucky’s life, Maizy realizes this is nothing new. This has been going on for generations. And her eyes are opened.

RS: How did you perceive racism when you were her age? Racism toward Chinese Americans, I mean.

LY: I didn’t feel it that much. I was born and raised in Los Angeles, and I grew up in Monterey Park, which now is mostly Asian. At the time when I was growing up it wasn’t, though. There was a mixture of kids. Now and then people would make fun of me, but I didn’t think about it. I didn’t think about race at all when I was growing up. When I moved to Florida in my early twenties, that’s the first time I really encountered racism. A lot of it wasn’t targeted racism. People were curious, but at the same time, I realized that I looked different to people when they complimented my English. Or they would say, “Do you know Mary?” “Who’s Mary?” “She’s Chinese.” “No, I don’t.” That kind of thing opened my eyes. When I was writing Maizy’s story, I was using aspects of that experience. When you kind of live in a bubble — Los Angeles is big, but with so much diversity it’s kind of a bubble — and you go someplace else, suddenly you’re forced to not only look outward but also look inward.

RS: What do you mean, look inward?

LY: You’re forced to look at yourself as other people see you. You might have an idea of who you are, but then somebody says something to you, or gives you a sideways glance, and you realize that how you perceive yourself is not how they see you.

RS: Right. And in a place like Florida, where you were surrounded with so many people who did not look like you, that became even more apparent.

LY: Yes.

RS: Got it. What was it like visiting Minnesota, for your Minnesota scenes?

LY: It was fun. I had been there a few times before, but I specifically went this last time to research. I sent my friend Henry, who lives there, a list of small towns I wanted to visit, and asked if he knew of others. I just wanted to immerse myself in that. It was freezing cold when I went; still, it was great to walk around these small towns. When we went to Chinese restaurants, I’d use the excuse of going to the restroom to sneak in the kitchen and look around. In some places I was the only Chinese person — other than the owners — eating there. But everybody was obviously enjoying the food.

One of the best discoveries was coming across the last bank Jesse James and his gang robbed. It’s a museum now, and I was just fascinated by the whole thing. I wove that incident into Lucky’s story, making one of Jesse James’s gang members a cook at the Golden Grille. In the book, Lucky ends up being a chef at the restaurant because the cook was killed during the bank robbery.

RS: Have you read A Free Life by Ha Jin? It’s an adult novel, and it’s about a young man who comes from China in the 1990s to go to school but ends up working in Chinese restaurants. The story follows him around the country, restaurant to restaurant, as his fortunes ebb and flow. It’s really terrific.

LY: I’m going to write that down, because I thought I’d read everything by him, but I don’t know that. I’m going to get that.

Every small town has a Chinese restaurant. Why was one of the questions I asked myself, even before this book, and I wanted to explore that. The history of Chinese restaurants in America is fascinating. The reason why there are so many Chinese restaurants and Chinese laundries in America is because, back in the day, cooking and cleaning were considered women’s work. Men wouldn’t do that — but the Chinese would. Chinese men would, and that became their foundation in this country.

RS: I wonder why Chinese cuisine took such hold in all the different kinds and parts of America.

LY: In my research, I found out that a lot of the dishes Chinese restaurants serve are really Americanized versions. Things like chop suey — that’s American. They would take the local dishes, the local produce, and they would make it just exotic enough to be interesting, but the ingredients were familiar. I think that slowly, once people got used to eating Americanized Chinese food, restaurants started introducing other things to it. I also learned that McDonald’s wanted to do General Tso’s chicken (again, not really Chinese food), but the person who created it wouldn’t sell them the recipe. So, McDonald’s created their own with their own dipping sauces and called it Chicken McNuggets.

RS: And a legend was made. You’re making me laugh now because one of my mother’s favorite dishes for leftovers she called American chop suey.

LY: Just put everything in there?

RS: But if chop suey’s American to begin with...

LY: It’s redundant, yeah.

RS: Where would you say that this story actually started? With a character? With a Chinese restaurant? What came first?

LY: I guess it started with the character. The impetus was taking a person who was familiar with something and putting them in a different setting and seeing what happens. There’s a reference early on in the book to The Wizard of Oz, because it’s a similar kind of story: Dorothy is in one place, she wakes up and she’s in another place she doesn’t recognize. At the end, when she says she wants to go home, Dorothy realizes that she’s been home the whole time. In my book, at the very end, Maizy is at the wishing well and she talks about her initial wish that she could be home. She says, “What I realize now is that I’ve been home all summer.”

RS: How did you handle the shifts between Maizy’s story and the segues, via her grandfather, to the historical account of her great-great-grandfather?

LY: It was so hard to write. I had never done historical fiction before. I was so afraid of getting it wrong, and I did a lot of research. I basically wrote two different books. I wrote Lucky’s book, and I wrote Maizy’s book, and then I melded them together — cutting down Lucky’s story, because it was originally much longer and could have overtaken Maizy’s story. It was quite an effort to blend the two.

RS: How much of Maizy is you?

LY: I’m probably more her mother, with the food styling and all. But I think I have the same curiosity that Maizy has. She’s probably a little bit more outgoing than I am. When I was Maizy’s age, I didn’t really know anything about my ancestors either. I knew my grandmother very well. I knew my grandparents. But I never asked them about where they came from, and I never asked my parents. Now I talk to my parents about that kind of stuff all the time, but I wish I had asked my grandmother and grandfather.

RS: Do you think you were being nudged not to ask?

LY: Probably somewhat. My grandparents spoke Chinese and some English. When I was younger, they would speak Chinese to me, and I could understand them. I spoke English to them, and they could understand me. As they got older, however, they just spoke Chinese; I don’t speak Chinese, so the language kind of was a barrier. But to them, it was all about being American. They came over when they were young, in their twenties.

RS: Assimilate above all.

LY: Assimilate. This anecdote kind of encapsulates it. When my mother was small, my grandmother would go to the butcher and my mother would translate for her. Wanting to show the Chinese butcher (who only spoke Chinese) that she was American, my grandmother would speak English and my mother would have to translate into Chinese for him. He would then speak Chinese to my mother, and my grandmother would pretend she didn’t understand him. My mother would have to translate what he said into English.

RS: It sounds like your family has given you a lot of material.

LY: I’m seeing a lot of people saying the book is about race. Yes, that’s part of it, but it’s truly a story about a family. It’s a story about this one family in past and present.

RS: And in the summertime. That’s one thing I kept thinking of, these great summer stories. Your characters get so much more latitude when they don’t have to spend eight hours in school every day.

LY: Yes, absolutely. In an early draft, Maizy was in school for three months before getting out for the summer. It just took up so much space, being in class, and it added so many more characters. I realized, okay, in some sense it’s a simple story, so I don’t need all that commotion with school.

RS: It’s a simple story, but all of your characters have a lot going on. Daisy, the assistant chef. Lady Macbeth. I thought Lady Macbeth was the guilty party.

LY: As I was writing it, I didn’t know who the guilty party was. Who was it? Did Lady Macbeth pay somebody to do it? Was it Eric? I didn’t know. And then I wrote myself into a corner. How am I going to get out of this one?

RS: Is that telling us something about the way you write in general? Is it very seat-of-your-pants, not a lot of planning?

LY: It’s both. I do a very detailed outline, and then I throw it away. I always outline, and then as I’m writing, this sounds so corny, I let the characters lead me.

RS: Well, I think they led you to a good place this time.

LY: Thank you.

Sponsored by

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!