Nikki Grimes and Brian Pinkney Talk with Roger

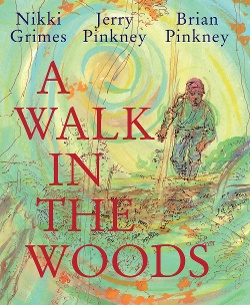

A Walk in the Woods was to be Nikki Grimes and Jerry Pinkney’s first collaboration, but Jerry sadly died before the book could be completed. Below, Jerry’s son Brian, himself already an acclaimed creator of picture books, and Nikki recreate the intriguing (and slightly supernatural?) story of how the book finally came to be.

Talks with Roger is a sponsored supplement to our free monthly e-newsletter, Notes from the Horn Book. To receive Notes, sign up here.

Sponsored by

Holiday House/Peachtree/Pixel+Ink

A Walk in the Woods was to be Nikki Grimes and Jerry Pinkney’s first collaboration, but Jerry sadly died before the book could be completed. Below, Jerry’s son Brian, himself already an acclaimed creator of picture books, and Nikki recreate the intriguing (and slightly supernatural?) story of how the book finally came to be.

A Walk in the Woods was to be Nikki Grimes and Jerry Pinkney’s first collaboration, but Jerry sadly died before the book could be completed. Below, Jerry’s son Brian, himself already an acclaimed creator of picture books, and Nikki recreate the intriguing (and slightly supernatural?) story of how the book finally came to be.

photo credits: Aaron Lerner & Chloe Pinkney

Roger Sutton: It seems to me that this book, right from the start, is kind of haunted — in a good way. Nikki, you certainly weren’t expecting that when you wrote the story, were you?

Nikki Grimes: No, not at all. I didn’t even know what the story was going to be. Jerry and I had agreed on a general theme; we knew we wanted a book about Black characters engaging in nature, because we don’t see enough of that in children’s books. The story sort of happened along the way. When art became life, nobody could have been more shocked than me.

RS: Had the story been completed by that point?

NG: Oh, yeah. The story was done, and Jerry had already started on a dummy. We had a virtual meeting with the art director and the editor and went through it page by page to see what worked, what didn’t, what needed to be adjusted, all of that, before he started on the final art. So I knew Jerry was working on it, but nobody knew how far he’d gotten, whether or not he’d finished, at the point that he left us...without permission.

RS: You say in your afterword that Jerry left behind tight sketches. What does that mean?

Brian Pinkney: Those are his line drawings on vellum. He would put them on the lightbox and put his watercolor paper on top to do the finishes. You see in the book the lines he drew with a certain kind of thin brown Sharpie marker — very detailed. Yet there’s also a lot of underdrawing in there, because he was still working out things like, should the squirrel be leaping, or on the branch? Is the deer lifting its foot, or is it down? When I went in, I chose the lines I thought he would choose, or the ones that I felt were needed — but you can see the ghost image of his underdrawing.

RS: What an amazing way to collaborate, both with each other and with Jerry.

NG: Yeah.

RS: Didn’t it creep you out a little, too?

BP: At first it did. And then it was like, Well, of course. That’s my dad. He always had a little magic in him. The final illustration, of the boy with his father’s hand on his shoulder... My dad had his hand on my shoulder the whole time I was working on this.

RS: His hands under your hands, too.

BP: Yeah.

RS: How did you marry your watercolors with your father’s work?

BP: I had his lightbox and all his artist’s paper that he didn’t use, and I would put his drawing on the lightbox with the watercolor paper on top of it. You turn all the lights out and turn the lightbox on, and you can see the image. The problem then was I couldn’t see the watercolor. I realized his line wasn’t dark enough, so I went over his drawing with my brush line and then painted on top of that. Originally, I thought I would use my brush line, but I realized it was nowhere near as genuine and unique as what he had done. My niece Charnelle Pinkney Barlow digitally combined and adapted his drawings and my artwork to make the final images.

I mention in the back of the book that while we were on summer vacation, I was showing these big, abstract, warm-color paintings to my dad, and I said, “I don’t know what these are for, but they’re underpaintings for something.” When the time came, I would do some of those on my own, put his sketches underneath, and then go back in. For each image, I probably did about four or five versions to find the one that resonated.

RS: Nikki, what were you doing all this time?

NG: When Jerry and I originally talked about doing a book together, we really didn’t know what that was going to be. I started coming up with story ideas that I’d send to him, and he would say, “No, no, no; I want this book to be a conversation.” He kept using the word conversation. So I’d go off and come up with another story idea and send that to him. At a certain point I started to get, Okay, he doesn’t want me to create a story and send it to him to illustrate. Somehow this has to be something that originates from us both. I’ve never done that before.

He would talk to me about his walks in the woods, anecdotes connected with whatever he’d seen on a particular walk, and I would say, “Stop, Jerry, that story you just told me — write it down and send it to me.” He would also have sketches that he had done on that walk, or right after it. I started writing poems inspired by his stories and images — individual pieces, disparate, not connected in any way. He kept asking where it was going, and I would say, “Just trust me; we’ll get there.” It took a while before I knew. That didn’t scare me, because I approach all of my work like a jigsaw puzzle. I don’t worry about sequence; I’ll write pieces and later I’ll lay them all out and see how they fit together organically. That was the way I was approaching this, but I still needed some sort of throughline. I came up with the idea that a mystery would tie all these pieces together. My mystery, because I’ve never written a mystery in my life, is going to have to be really basic. So it’s a treasure hunt. The character’s going to go and find this treasure, and the treasure is all of these drawings that connect to the poems I wrote.

RS: It was a conversation.

NG: It really was a conversation. He was checking in with me regularly, and meanwhile I was researching the area. I needed to have the lay of the land where this character was going to be moving, walking. The flora and fauna, what else was available to draw on. It was in doing that research that I came across, for instance, the ruins of a house with a chimney, which became the place where the treasure was laid. There were other elements of the story that I found through research, like the Native American water storage house.

RS: These are the woods that Jerry walked in? Where are they?

BP: It’s called McAndrews. It’s an old estate across the street from our house. It’s all ruins. As kids, we would run and play and dig for treasure. I knew that chimney that Nikki mentioned. When I was there doing research for the book, an eagle took off into flight, just like in the story. There were two deer that ran off with their little tails waving. I saw that before I read Nikki’s poem about deer tails waving like white flags. It was all very mystical.

I love this idea of a conversation. Nikki’s heard this story, but initially, when we were trying to figure out how much work I would do on the book, I said, “My dad did so much work already. He did the drawings. He did the research. It was his idea.” So I’m thinking fifteen, thirty percent would be my contribution to the project. We settled on twenty-five percent. I’m working on the paintings, and I’m thinking I’m going to go in with my black line and go over his lines. I had a dream one night that I was a teenager, and my dad said to me, “You can’t go out to dinner with us. You were supposed to do that paper, and you added twenty-five percent more than you were supposed to.” And I woke up thinking, Twenty-five percent. Oh my goodness. I’m not supposed to go back in and add more of my own stuff. So the conversation continues, even now.

RS: And now it’s a conversation between three people. Nikki, can you say a little bit more about you and Jerry talking about the lack of representation about books for kids about Black people in nature? We did an article about that in The Horn Book some years ago. There’s such an tendency to put Black characters in urban environments.

NG: Always. That was the reason I wrote Southwest Sunrise. That was the point at which I realized I’m going to have to start addressing this, because I’m not seeing it nearly enough in children’s literature. But we still have a long way to go on that score. The default always is urban, urban, urban. You know, we’re out West, we’re on ranches, we’re in the mountains, we’re in Appalachia. We’re in a lot of places that aren’t urban. We really need to see that.

NG: Always. That was the reason I wrote Southwest Sunrise. That was the point at which I realized I’m going to have to start addressing this, because I’m not seeing it nearly enough in children’s literature. But we still have a long way to go on that score. The default always is urban, urban, urban. You know, we’re out West, we’re on ranches, we’re in the mountains, we’re in Appalachia. We’re in a lot of places that aren’t urban. We really need to see that.

RS: Do you have a daily walk?

NG: I used to walk quite a bit. I have to get back to that. I like to discover things along the way, see what I see.

BP: I live in Clinton Hill, a part of urban Brooklyn that’s regentrified, so all the Black people kind of left. My studio used to be in Bed-Stuy, about twenty blocks away. I'd do that walk every day or every other day. Now it’s in Cypress Hill, and I walk around the reservoir there.

NG: I drive into nature. I’ll drive somewhere and walk.

RS: Nikki, have you been up to Jerry’s house?

NG: No. When we started talking about this, it was fall 2019. The plan was I would visit, and we would go for walks every day in the woods. I was going to take my camera and videotape and make sketches, and we were going to brainstorm. And then COVID hit, and it was like, well, change of plans. I ended up asking Jerry to make videos as he went on his walks and send them to me. Initially he was sending me videos of the canopy. And I’m like, “The canopy is beautiful, Jerry, but I need to see the ground and where the boy is walking.” What was cool about that was he started paying more attention to the ground. He’d write to me, excited about something he’d seen that he’d never noticed before.

BP: A virtual walk in the woods. She could watch the video while she was walking.

RS: Brian, were you aware of this book as your dad and Nikki were working on it?

BP: I was aware there was a book about nature that he was doing with Nikki, but I didn’t know what the story was. He would show me his sketchbooks. While I was working on the book, we were going through all my dad’s stuff and my mother found the actual drawings that he had done. We decided to include those in the book, straight from his sketchbook.

NG: Magic. Everything about this book was guided.

RS: It does feel like it, that the theme of your story has been reflected in the creation of the book itself. I have no words for that.

NG: It was a goosebumpy kind of thing. It was one of those God projects. I just see God’s hand all over it. I couldn’t make this stuff up. You couldn’t make up this story.

BP: You did make it up, but you didn’t make it up. That’s what’s scary about it.

RS: It’s kind of like you made it up, and then it happened.

NG: It feels like that. And it’s so strange, because as I said, I didn’t even know where the story was going to go. But I’m always looking to make an emotional connection with my reader. I needed a reason that this kid was going to go on the search that was going to be powerful and that would drive the story emotionally. I chose death, the loss of his dad. It’s not like I set out to write a book about loss. I wanted to write about the healing power of nature. That was a catalyst for everything else that happens in the story. But it wasn’t planned from the beginning. You know, it becomes its own thing. It takes on a life of its own.

BP: It worked on me, the healing power of nature. It got me back in the woods, helped me understand my dad a little deeper.

RS: This book is almost a commemoration of how Jerry felt about animals and nature. That picture of the eagle in flight — I don’t know anybody else who could draw that. You can see, in that picture and in the pictures of the other animals, how attentive Jerry was to nature, and how much it meant to him. Is that something you experienced growing up, Brian?

BP: Yes. I will say that his love of nature kept evolving over time. I remember we went fishing when I was a kid, and I caught an eel. I was totally disgusted by it, and my dad took it off and threw it in the woods. Later, he probably would have put it back in the water. He would find bugs in the house and catch them, put them out. Tell me stories about the little chipmunks around his studio, put birdfeeders up in the right places. He talks about it in Just Jerry, how he accidentally shot a bird and was heartbroken by it. And again, even that eagle drawing, he had several versions that he was working on.

RS: Those are all based on his sketches from life, as far as you know?

BP: From life, from books, a combination. When he first started drawing animals, it would be from research and books. He got to the point where he understood the anatomy so well, he could manipulate the wingspan. It wouldn’t just be, Oh, I have a photograph of an eagle in flight; I’m going to copy that. He would start manipulating and expanding. Or he’d draw the knuckles on a squirrel. I thought, who does that?

RS: The exactness. There’s such life in those animals. They’re almost breathing.

BP: Yeah. He would choose the position he wanted, and he would be able to move them around in his mind and then draw them.

RS: Your legacy from Jerry — burden, legacy, combination of both? He’s a lot to live up to, right?

BP: It’s just the way I was brought up. I used to play underneath his drawing table while he was working. I modeled for his books. It’s just who he and I were as father and son. People say, “It must have been really hard; was he very critical?” No, he loved everything I did. Anything I drew, he would say, “That’s beautiful, that’s amazing.” He was such a loving, endearing person. It wasn’t just the way he presented himself. He really was that way. He was that way in our relationship.

RS: You’ve both done an incredible job creating a great book in and of itself, but it’s also a great tribute to its third collaborator, who’s no longer with us. Congratulations.

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!

Vanessa Hatter

Wow! There are no words. I work in a library and I sometimes help wrap the books in cellophane so the books can last longer and I ran across this book. I don't usually look at the books as I wrap them, but this one caused me to stop and look inside. You don't usually see 3 names on a cover so I wanted to know the story. At first I only read the back flap and I couldn't wrap the book anymore as it was just too precious to handle. Then today on 11/27 I went back to wrapping and I read the front flap, to find out the content of the story is a conversation between a dad and son that transcended death. Literal goosebumps. Of course I had to know if Nikki knew of the timeline and how coincidental it was. I just had to know the story behind a most interestingly haunting story. I still haven't read it but I look forward to experiencing this so organically. Also, Roger, what a beautiful job in facilitating this interview. Very well done on everyone's parts. I am so in love.Posted : Nov 27, 2023 10:09