Allison Grover Khoury takes in the thoughtful beauty and wisdom of Michaela Goade's Berry Song, with its gorgeous art and powerful message.

[Many Calling Caldecott posts this season will begin with the Horn Book Magazine review of the featured book, followed by the post's author's critique.]

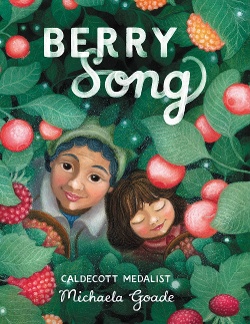

Berry Song

Berry Song

by Michaela Goade; illus. by the author

Primary Little, Brown 40 pp. g

7/22 978-0-316-49417-5 $18.99

In Goade’s (Caldecott Medalist for We Are Water Protectors, rev. 7/20) latest picture book, set “on an island at the edge of a wide, wild, sea,” a Tlingit grandmother teaches her granddaughter “how to live on the land.” First, they gather what they need from the water. Then they enter the forest to pick berries; the berries’ names serve as an evolving refrain, and the land is also frequently and reverently referenced. As they pick, they sing to the flora, the fauna, and the ancestors: “We take care of the land…As the land takes care of us.” Once they have collected what they need, they head home. After their subsequent feast, they say “Gunalchéesh,” giving thanks for the food. The story ends with the girl passing on the song and her grandmother’s knowledge to her younger sister. Goade’s lush, brightly colored art vividly portrays the landscape. In many of the images, the child and her grandmother are shown intertwined with the forest, with which they are deeply connected. In one scene, the grandmother and granddaughter are the same green as the forest, and their hair and faces are covered by leaves. In another image, we see a totem pole faintly outlined within a tree. An author’s note tells more about Goade’s childhood; her life in Sheet’ká, or Sitka, Alaska; and the song in the book. Endpapers name the berries in both English and Tlingit. NICHOLL DENICE MONTGOMERY

From the July/August 2022 issue of The Horn Book Magazine.

What a privilege it is to read and take in the thoughtful beauty and the wisdom that Michaela Goade offers us in the story and art of Berry Song. This book gives us a precious opportunity to breathe in the forest, the sea, the creatures living there, the islands and the berries (!). We witness the ways that a traditional grandmother lovingly trains her granddaughter to gather food from the sea and forest with reverence and gratitude.

So how does one write about the brilliant technique of a Caldecott gold medal winner? How does one describe the elegance and the true partnership between her tender story and her gorgeous illustrations? As I was reading this book over and over, I thought about how much we need this book, for all its exquisite art, yes. But as importantly, we need Berry Song as people living on our planet. We are facing the dire consequences of our lack of insight and understanding of our true connection to our home, Earth. The world desperately needs to learn to listen to Indigenous peoples, who understand the sacredness of our planet and how to care for it.

Let’s discuss the book by beginning with the cover: the background is deep forest green, and grandmother's and granddaughter’s faces are wreathed in berry branches. This color and design continues on the endpapers. I am always intrigued by endpapers. Do they influence Caldecott committee members in any way? I have no idea, but I do love the endpapers here. Front and back, they are a deep pine green embellished with flowing stems of all the bright pink, blue, red, and yellow/orange berries featured and found in the woods. They are named in Tlingit and English so that those who don’t speak Tlingit can learn, and those who do can read them in the original language.

The story begins with our adorable narrator and her grandmother in a boat while Grandmother is showing her “how to live on the land.” Grandmother teaches her to take great care in their stewardship of the land as they harvest what they need — to eat, to live. She is also teaching her to sing to the world, to honor the ancestors, to be grateful, to sing her gratitude, and let the forest or the berries, or sea or the animals know they are there. Some of my favorite illustrations are the granddaughter singing to communicate with the world as they gather.

The illustrations are either soft with a tinge of the ethereal, or incredibly carefully detailed and richly colored. Some illustrations are a fine balance of both. The shades of color are contrastingly deep and rich or light and feathery.

The berries are miraculous, page after page. Each one is a bright pop of color, called “jewels” by the granddaughter — they are so pretty and mouth-wateringly delicious. Berries like thimbleberry, swampberry, bogberry, chalkberry, lingonberry, raspberry, bunchberry, cranberry, and more. There are some I didn’t know, so I enjoyed a half hour of research with my nine-year-old to learn more. In the excellent two-page back matter, there are pictures of hands (I hope they are Michaela Goade’s) holding berries.

(Although the back matter won’t influence an illustration award consideration — it is marvelous and fills in what is delicately implied in the story and art.)

The pacing of the book, both art and story, are unhurried but always in motion. Whether gathering herring eggs or salmon from a swirling sea teeming with life, or gently picking berries in a still forest, the movement and the stillness are often captured in the same scene. One place where this is most effective is a double-page spread where we see Grandma on one page, silhouetted among leaves and branches with accompanying text, “Grandma tells me, 'We speak to the land…'” On the opposite page is our girl, silhouetted in branches with leaves and berries, turning her face up and receiving an offering from the forest of drops of water bouncing off her nose as she replies, “As the land speaks to us.”

This powerful message is a refrain throughout the book — the grandmother reminding her granddaughter, “We are a part of the land,” and her granddaughter replying back, “As the land is a part of us." And the illustrations testify again and again how this is so.

On other pages, the sea waves and swirls, or the forest, is dark and magical or light and magical. And the berries — popping colorful reds and pinks and blues among the green leaves and the swirling green light and darkest green close to the ground.

We see animals going about their food-gathering while grandmother and granddaughter are doing the same. They are never alone in the forest. In one particularly glorious double-page spread, they sit on a hillside at the end of the day, looking out over a resplendent sea at sunset, berry baskets at their sides. Eagles keep watch from a treetop and the air above.

When grandmother and granddaughter head home, we are treated to meeting more of the family in the kitchen, cooking the berries as well as lots of delectable tarts, pies, scones, crisps, and jars of jams. “'Gunalcheesh,' we say, giving thanks.”

The book closes with winter coming, and the forest resting for a season. This double-page spread is in the softest blues, with white snow bringing the winter, and all seems peaceful. A raven with a naughty glow in its eye feasts on some bright red berries. The last page shows our girl now older, taking her younger sister into the forest to learn and to pick berries. Wisdom, love, and respect for the gifts of the world are passed on to a new generation.

So: to the Caldecott Award criteria. Is this book, and are these illustrations, excellent? YES!

Do they interpret and enrich the story? YES!

Is the style appropriate to the story? YES — more than YES!

Is the plot, theme, characters, setting, mood or information delineated through the pictures? YES!

Is this gorgeous narrative further enriched through the pictures? YES!

Is this an excellent presentation in recognition of a child audience? YES!

My every hope for Caldecott recognition is with this extraordinary and beautiful book. And I say thank you to Michaela Goade. Gunalcheesh!

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!