Between Fiction and Reality: The Playground of Metafiction

Metafiction calls attention to how narrative works within the narrative work. Crockett Johnson provides an early example. In Harold and the Purple Crayon (1955), the title characters collaborate to show off the elements of story and of picture book creation. Harold takes center stage as the primary character whose journey to walk in the moonlight begins once he takes the crayon in hand. Immediately, the book delivers on the narrative requirements of character, plot, and setting; later, it provides point of view, conflict, and theme.

In 2024, Mercier guest curated "Pictures at Play: Metafiction in Art" at The Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art. It featured picture-book images that "illustrate how artists experiment with styles, typography, and page design to disrupt the rules of how books usually work." The following article is inspired by her work on the exhibit. Visit carlemuseum.org/explore-art/exhibitions/past-exhibition/pictures-play-metafiction-art.

Metafiction calls attention to how narrative works within the narrative work. Crockett Johnson provides an early example. In Harold and the Purple Crayon (1955), the title characters collaborate to show off the elements of story and of picture book creation. Harold takes center stage as the primary character whose journey to walk in the moonlight begins once he takes the crayon in hand. Immediately, the book delivers on the narrative requirements of character, plot, and setting; later, it provides point of view, conflict, and theme.

Metafiction calls attention to how narrative works within the narrative work. Crockett Johnson provides an early example. In Harold and the Purple Crayon (1955), the title characters collaborate to show off the elements of story and of picture book creation. Harold takes center stage as the primary character whose journey to walk in the moonlight begins once he takes the crayon in hand. Immediately, the book delivers on the narrative requirements of character, plot, and setting; later, it provides point of view, conflict, and theme.

The world-building highlights fiction as illusion by accenting Harold’s role as an artist with the necessary tool to create what he imagines. Ultimately, he tells the big story of how story itself is made: by an author and, in the case of a picture book, an illustrator. Adding to these thematic elements, Johnson presents this child author/illustrator as aware of his creative abilities to relieve his own boredom.

In drawing attention to the artifice of fiction, metafiction also employs the reader as co-story-maker. The reader complements Harold and his purple crayon, filling in narrative gaps by following the purple line across the time and space of the story. The purple line outlines character, plot, conflict, rising and falling action, and theme as it moves across pages, into page-turns, and across gutters. Not only does the line act as a vehicle of narrative, but it also presents the storytelling conventions of the picture book.

Metafiction can direct attention to the materiality of the book as an object. Early examples include Peter Newell’s The Slant Book (1910), a parallelogram-shaped book that follows the hair-raising ride of a runaway go-cart, and Dorothy Kunhardt’s Pat the Bunny (1940) with its fake-fur-filled outline of a bunny and direct address to the reader: “Now YOU pat the bunny.” Contemporary works such as Open This Little Book by Jesse Klausmeier and Suzy Lee (2013), Another by Christian Robinson (2019), Mel Fell by Corey R. Tabor (2021), and Vashti Harrison’s 2024 Caldecott Medal–winning Big invite readers to manipulate the book, to turn it around, to open folds and gatefolds to discover narrative possibilities.

Books such as The Adventures of Sparrowboy by Brian Pinkney (1997) and even the informational Redwoods by Jason Chin (2009) also call out the book as an object when they apprehend characters in the act of reading. In images where the reader-in-the-book holds an open page, the illustrators put the characters’ hands at the very place where that reader positions their hands; thus, the reader holds both the book they read and the book being read in the book they read. Metafiction invites the reader into the funhouse of fiction, disrupts something, and enjoys what happens when the boundaries between fiction and reality blur.

Books such as The Adventures of Sparrowboy by Brian Pinkney (1997) and even the informational Redwoods by Jason Chin (2009) also call out the book as an object when they apprehend characters in the act of reading. In images where the reader-in-the-book holds an open page, the illustrators put the characters’ hands at the very place where that reader positions their hands; thus, the reader holds both the book they read and the book being read in the book they read. Metafiction invites the reader into the funhouse of fiction, disrupts something, and enjoys what happens when the boundaries between fiction and reality blur.

Fundamentally, metafiction predicates differences between reality and fiction. In a thirtieth-anniversary tribute (Horn Book Magazine, May/June 2020) to Black and White, a touchstone of metafiction, I explored the ways David Macaulay exploits the boundaries of the picture book to foreground metafiction as “literary recreation,” bursting with gaps that conscript the reader as co-creator, and requiring the reader to tease out layers of narrative. How does one read four art styles? Four stories? Or is there one story? What clues does the title provide, and what does that final image of a hand, a dog, and a train station mean?

Jon Scieszka and Lane Smith’s The Stinky Cheese Man: And Other Fairly Stupid Tales arrived two years later and tapped other metafictional strategies:

• the fourth-wall-breaking narrator who addresses the reader;

• a polyphonic world where voices compete for control;

• references to other texts (intertextuality);

• subversion and parody of retellings;

• experimentation with font and page design imbued with narrative significance;

• and disruption of expected elements of a book itself.

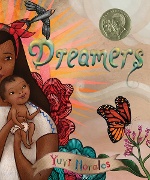

Today, intertextuality may be one of the most active metafictive devices because it invites the reader into a familiar place and then unsettles that familiarity. Yuyi Morales’s 2018 work Dreamers includes pictures of well-known books in a library; and then it flips the idea of intertextuality as referring to supposedly canonical works to an image that refers to an alternative canon and yet-to-be-created books. As a woman stands and stitches a huge book, a child stands beside her; is the child packing or unpacking their backpack with the less familiar or even unfamiliar books scattered around them? The child holds a pencil to signal that influential texts have yet to be created.

Today, intertextuality may be one of the most active metafictive devices because it invites the reader into a familiar place and then unsettles that familiarity. Yuyi Morales’s 2018 work Dreamers includes pictures of well-known books in a library; and then it flips the idea of intertextuality as referring to supposedly canonical works to an image that refers to an alternative canon and yet-to-be-created books. As a woman stands and stitches a huge book, a child stands beside her; is the child packing or unpacking their backpack with the less familiar or even unfamiliar books scattered around them? The child holds a pencil to signal that influential texts have yet to be created.

Metafiction challenges the more comfortable critical stance that most of us occupy as we write reviews, engage in scholarship about literature, recommend books to readers, or teach young people how to read. While we might seek the single meaning of a text, metafiction insists on multiple meanings. In a 2017 review, Publishers Weekly captured the possibility of endless meanings that occur with the metafictive practice of nesting in Red Again by Barbara Lehman and its earlier companion title, The Red Book (2004), calling them “a pleasing and perplexing Möbius strip of a story.”

Pleasing and perplexing characterize the curiosity at the heart of metafiction. I teach metafiction because it makes the rules of fiction (or genre or picture book) visible in ways that can move readers into critical considerations. I open class with a case study of David Wiesner’s The Three Pigs, published in 2001, and track how students’ initial reader response moves into critical inquiry. Our conversations go something like:

Pleasing and perplexing characterize the curiosity at the heart of metafiction. I teach metafiction because it makes the rules of fiction (or genre or picture book) visible in ways that can move readers into critical considerations. I open class with a case study of David Wiesner’s The Three Pigs, published in 2001, and track how students’ initial reader response moves into critical inquiry. Our conversations go something like:

• Cool! Retellings are fun when we’re in on the joke.

• Even better, this retelling has limited words. Even though I’m an ironic reader because I’m in on the joke, I still have to puzzle out what this book means. And as I do so, I realize I’m also figuring out how this book creates meaning. In doing that, I’m aware that I’m directly engaged in the process of meaning-making.

• Awesome! The picture book uses many art styles in the retelling. Sometimes the art is realistic, sometimes it’s surrealistic, sometimes cartoonish. Why? To what effect?

• Wait! Sometimes the style of the art changes from page to page. What’s happening? How can the same pig move from its realistic rendering into a cartoon character just by crossing the gutter? LOL, and why?

• This book does make me laugh, and it makes me think. As a student of picture books, I recognize some of these art styles; they’re visual quotations. The pigs and the wolf look a whole lot like L. Leslie Brooke’s characters in his illustrations for 1904’s The Story of the Three Little Pigs. And that scaly dragon looks awful familiar, too; didn’t he debut in another Wiesner book? Visual enigmas fill this book; and yet, can they be solved? Should they be solved? Do they all have to lead to the same conclusion?

• And what’s going on with nesting here, with images inside images? Where’s the beginning and the ending? Don’t books have to follow rules about these things?

• Strange things happen in the book that unseat expectations. Scenes start to tilt, tight compositions give way to lots of white space, pages of a book within this book begin to float and scatter, the pigs even fold a page into a paper airplane and ride it in and out of multiple picture spaces.

• I enjoy the ironic position of recognizing what should be and isn’t throughout this book. I am gratified by seeing through the fiction, but I’m not always sure what’s on the other side. Shouldn’t I have all the answers? Will I ever have all the answers?

I hope not. Metafiction opens the promising space of not-knowing. The open-endedness allows more questions, and more questions allow more speculation, and more speculation allows more self-knowledge and more knowledge about how books might work…or not.

From the May/June 2025 special issue of The Horn Book Magazine: Perception and Reality.

Single copies of this special issue are available for $15.00 including postage and may be ordered from:

Single copies of this special issue are available for $15.00 including postage and may be ordered from:

Horn Book Magazine Customer Service

magazinesupport@mediasourceinc.com

Full subscription information is here.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!