Regina Linke's "art [for Big Enough] is distinguished for the ways in which it challenges boundaries and achieves harmony between traditional and contemporary, reality and fantasy, big and little."

Linke’s story based on Chinese philosophy and set in rural China, celebrates a Ah-Fu, a young boy who successfully retrieves the family’s ox, despite warnings from his grandfather, a flock of swallows, and a frog, that he is not big enough, respectively, to ride the ox, lead him by the horns, and herd him from behind. In the children’s literature courses I teach, I encourage students not to make assumptions about all children when they critique books. When I first encountered Big Enough, I must admit, though, I was drawn to the proverbial small child who discovers he is big, or in this case, big enough. I remembered when my four-year-old son asked me, after introducing him as “my little guy,” “Did you forget that I am big now?” Perhaps others can recall such experiences with children they’ve encountered. And yet, the book’s Caldecott merit lies not in its depiction of a universal childhood experience of feeling little or big, but in the ambiguity implied in the word “enough” that modifies “big.” Linke’s art is distinguished for the ways in which it challenges boundaries and achieves harmony between traditional and contemporary, reality and fantasy, big and little.

Linke’s story based on Chinese philosophy and set in rural China, celebrates a Ah-Fu, a young boy who successfully retrieves the family’s ox, despite warnings from his grandfather, a flock of swallows, and a frog, that he is not big enough, respectively, to ride the ox, lead him by the horns, and herd him from behind. In the children’s literature courses I teach, I encourage students not to make assumptions about all children when they critique books. When I first encountered Big Enough, I must admit, though, I was drawn to the proverbial small child who discovers he is big, or in this case, big enough. I remembered when my four-year-old son asked me, after introducing him as “my little guy,” “Did you forget that I am big now?” Perhaps others can recall such experiences with children they’ve encountered. And yet, the book’s Caldecott merit lies not in its depiction of a universal childhood experience of feeling little or big, but in the ambiguity implied in the word “enough” that modifies “big.” Linke’s art is distinguished for the ways in which it challenges boundaries and achieves harmony between traditional and contemporary, reality and fantasy, big and little.

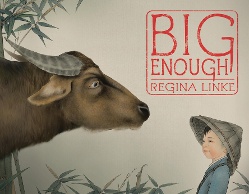

I will discuss the merits of Linke’s painting technique that sets this book apart from others. But first, I’d like to focus on the book’s “Excellence of pictorial interpretation of story, theme, or concept,” a Caldecott criteria. With sophisticated visual complexity, Linke invites readers to ponder the relativeness of size. She doesn’t just adjust the scale of characters and settings by zooming in and out, she also plays with Ah-Fu’s proportions relative to his animal guides. On the front jacket, for example, Linke tucks Ah-Fu into the lower right corner, where he occupies less than one eighth of the image, while the ox dominates the space. With the cover open, the ox fills most of the wrap-around illustration and even then, his back end doesn’t fit, making him seem even bigger and Ah-Fu even smaller. On the book’s spine, a shrunken Ah-Fu nestles between the author’s name and the book’s title, as if Ah-Fu is an insect hiding in the ox’s fur. As the story begins, readers learn that Ah-Fu “was so small he often got lost, especially in his own imagination.” In his double-page spread daydream, Linke places Ah-Fu, relatively large and centered on the verso and offers counterpoint to the descriptors “small” and “lost.” Later, when Ah-Fu first encounters the frog, she appears frog-sized compared to Ah-Fu. At the page turn, though, the surreal frog (perhaps a visual nod to David Wiesner’s Caldecott-winning frogs) fills the entire verso, while Ah-Fu, now tiny on the recto, barely reaches the top of the smallest plant. Meanwhile, the ox’s disproportionately large tail overshadows Ah-Fu and traverses the entire upper half of the recto. But then, when Ah-Fu braces himself to lead the ox by the horns, he is so big his head fills most of the recto and expands beyond the top, right, and bottom edges; here, he appears even bigger than the reader.

Throughout these shifts in scale, Linke invites readers to assume different perspectives relative to Ah-Fu. When he cries, “I’m just not big enough,” after tumbling down a hill–or is it a mountain?–Linke prompts the reader’s empathy with a birds-eye-view of Ah-Fu, tiny on the page, hiding in the looming shadow of the foliage. She commands respect for Ah-Fu when he appears giant on the page and gazes at the viewer, as he prepares to lead the ox by the horns. And she invites the reader into the story when Ah-Fu’s back faces the reader, as he embarks on the final challenge and herds the ox from behind. By constantly changing the reader’s point of view, and the scale of Ah-Fu relative to the other characters, Linke provokes questions about who is big and little and implies that size is neither static nor exclusive.

Linke also demonstrates the Caldecott criteria, “Excellent execution of the artistic technique employed” and “Appropriateness of style of illustration to the story, theme or concept.” Rendered digitally, with disciplined attention to traditional Chinese painting techniques, Linke sets the bar high for digital painting that is traditional enough. In an interview with Mel Schuit in Let's Talk Picture Books, Linke explains how she combines two distinct Chinese painting techniques, namely “gongbi being very precise, meticulous, colorful, and detail-oriented, and xieyi being looser, more idea – or emotionally driven.” She also discusses how she modified these techniques for a digital canvas and a contemporary Western audience. She paints immersive, detail-rich, serene watercolor-esque Chinese landscapes that are sometimes realistic and sometimes fantastical. She infuses her paintings with energetic, expressive, delicate linework. But perhaps most notable are the tender moments between Ah-Fu and the ox. She gives the ox tangible, soft fur and Ah-Fu flush, warm pink cheeks and a fuzzy partly shaven head. She connects them to each other with expressive eyes and tops Ah-Fu’s head with a gray straw hat that matches the ox’s gray horns. When Ah-Fu finally leads the ox by the horns, the duo’s bond, and their hesitation, is palpable. Linke paints worry lines and furrowed brows on the ox’s face and bends his legs tentatively, while she depicts Ah-Fu delicately tiptoeing on the cloudlike ground, gently leading the ox.

As any Caldecott-worthy book must, Big Enough offers a cohesive, artful book design, from the book jacket that differs from the case cover, to the storytelling end pages that begin the story in a realistic scale and earth-toned color palette and end in a fantasy-inspired purply-blue scene, to the pacing that toggles between moments that invite the reader to linger and anticipation-evoking page turns. Especially notable is the book’s title that resembles a traditional rounded-edged square Chinese seal, with unevenly printed red spot-gloss, as if it has been hand stamped. The bright red ink stands out from the book’s more subdued color palette and signals the story’s traditional roots.

Big Enough demonstrates excellence in perhaps the most indefinable of the Caldecott criteria, “Recognition of a child audience,” but not because of its universal message. Rather, because Linke’s illustrations insist that children are big enough for sophisticated, boundary blurring art. And the cover is big enough for a shiny gold sticker to accompany its Chinese seal-inspired title.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!