Black Girlhood and Newbery Winners

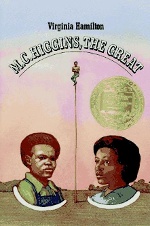

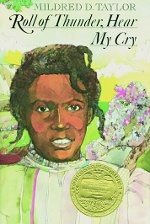

As a Black woman, African American children’s books scholar, and educator, I am dismayed that there have only been two Black women to win the Newbery Medal in its one hundred years. Virginia Hamilton was the first in 1975, for M.C. Higgins, the Great, and then Mildred D. Taylor won in 1977 for Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry.

Virginia Hamilton (left) and Mildred D. Taylor (right). Taylor photo: Jack Ackerman, The Toledo Blade.

As a Black woman, African American children’s books scholar, and educator, I am dismayed that there have only been two Black women to win the Newbery Medal in its one hundred years. Virginia Hamilton was the first in 1975, for M.C. Higgins, the Great, and then Mildred D. Taylor won in 1977 for Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry. In the last forty-five years, eight Black women have won a Newbery Honor but not the Medal: Carole Boston Weatherford, Alicia D. Williams, Renée Watson, Jacqueline Woodson, Rita Williams-Garcia, Marilyn Nelson, Patricia C. McKissack, and Sharon Bell Mathis. I’ve been grappling with what this means, and why it even matters that a Black woman has not won the Newbery Medal in forty-five years. Then I read this in the history section on the Newbery Award site:

As a Black woman, African American children’s books scholar, and educator, I am dismayed that there have only been two Black women to win the Newbery Medal in its one hundred years. Virginia Hamilton was the first in 1975, for M.C. Higgins, the Great, and then Mildred D. Taylor won in 1977 for Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry. In the last forty-five years, eight Black women have won a Newbery Honor but not the Medal: Carole Boston Weatherford, Alicia D. Williams, Renée Watson, Jacqueline Woodson, Rita Williams-Garcia, Marilyn Nelson, Patricia C. McKissack, and Sharon Bell Mathis. I’ve been grappling with what this means, and why it even matters that a Black woman has not won the Newbery Medal in forty-five years. Then I read this in the history section on the Newbery Award site:

The Newbery Award thus became the first children’s book award in the world. Its terms, as well as its long history, continue to make it the best known and most discussed children’s book award in this country.

These words reminded me of the impact that the Newbery Medal has on children’s literature in the U.S. The medal has an enormous effect on which books find prominent spaces on shelves in bookstores, classrooms, and libraries. Books that bear the Newbery seal are considered, without question, worthy of purchase and study. While a Newbery Honor helps a book to stand out, there is nothing like the gold medal given to the winner for a book’s reputation.

As I looked over the list of Black women who have won Newbery Honors over the past few years, I wondered what their winning the Medal instead might have meant for conversations around Black girlhood in the present. While Taylor’s Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry is a beautiful book, it gives us Black girlhood in the 1930s. Cassie and my grandmother are the same age. While the racism and sexism that Cassie faces in Roll of Thunder are still present today, it has changed shape and can often go unrecognized. What Piecing Me Together by Renée Watson and Genesis Begins Again by Alicia D. Williams, which won Newbery Honors in 2018 and 2020, respectively, give us is a look at the ways in which Black girls must navigate the world in the present.

As I looked over the list of Black women who have won Newbery Honors over the past few years, I wondered what their winning the Medal instead might have meant for conversations around Black girlhood in the present. While Taylor’s Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry is a beautiful book, it gives us Black girlhood in the 1930s. Cassie and my grandmother are the same age. While the racism and sexism that Cassie faces in Roll of Thunder are still present today, it has changed shape and can often go unrecognized. What Piecing Me Together by Renée Watson and Genesis Begins Again by Alicia D. Williams, which won Newbery Honors in 2018 and 2020, respectively, give us is a look at the ways in which Black girls must navigate the world in the present.

Genesis Begins Again has been compared to Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye and makes clear its connection to The Color Purple by Alice Walker through early references to that book. Genesis is the modern version of Pecola and Celie. If racism were a thing of the past, then Genesis would not feel the same hate for her dark brown skin as both Celie and Pecola did. She would not long to be lighter in the same way that Pecola longed for blue eyes. She would be confident in the skin that she is in, but instead she has internalized the colorism that pervades our society. How might having this book prominently placed on the shelf and as part of the curriculum help us to open up conversations about colorism and our society’s unrealistic beauty norms that affect not just Black women but all people?

In Piecing Me Together, Jade, too, is often made to feel as though she can’t fully be herself at the predominately white private school she attends. One wonders why she must travel across town to get a good education. Why isn’t the school in her own neighborhood equipped to educate her so that she can fulfill her dreams? How is she expected to excel in a space that doesn’t accept her for who she really is?

Although Rita Williams-Garcia’s One Crazy Summer (a 2011 Newbery Honor) is set back in the summer of 1968, it still gives us a look into how Black girls have been integral parts of the Black Freedom Struggle. In her acknowledgments, Williams-Garcia states, “I wanted to write this story for those children who witnessed and were part of necessary change. Yes. There were children.” Delphine and her sisters represent the many children who have fought and are still fighting for change. I can imagine them as any of the young girls we see marching in Black Lives Matter protests.

And then there are the four books by Jacqueline Woodson that have received Newbery Honors: Show Way (2006), Brown Girl Dreaming (2015), Feathers (2008), and After Tupac and D Foster (2009). Woodson’s work allows us to explore what it means to be a Black girl across generations. Show Way carries us from the unnamed Black girl who was enslaved to a portrait of Woodson and her daughter at the time of the writing — showing us the way Black women have nurtured Black girls. Brown Girl Dreaming depicts the author’s own childhood split between Ohio, South Carolina, and Brooklyn during Jim Crow. Through her, we learn the joys and the struggles of the Great Migration North that so many Black people made. Feathers, set in 1971, demonstrates how even though the laws had changed, segregation still remained. After Tupac and D Foster gives us a glimpse into the lives of preteen Black girls in Queens in the mid-1990s — Black girls who are beginning to push the boundaries of their blocks and their families while also coming to understand some of the challenges they will face as Black women.

If we were to read these Newbery Medal and Honor winners together, we would get a fuller picture of Black girlhood over time. If we start with Show Way, we are given an introduction and timeline of Black girlhood from the late 1800s to the late 1990s. Follow that with Taylor’s Roll of Thunder to learn about Black girls in the 1930s. We can then turn to Brown Girl Dreaming, followed by Feathers and One Crazy Summer, to understand Black girlhood in the 1960s and 1970s. Follow that with After Tupac and D Foster, Piecing Me Together, and Genesis Begins Again, and we have Black girlhood from the 1990s to the present. While not a complete picture, it starts to bring Black girls into focus.

Barbara Smith reminds us (in Toward a Black Feminist Criticism, 1977) that “for books to be real and remembered they have to be talked about.” I am not saying that it is the job of the Newbery Award to get these books into people’s hands. But the Newbery does have the power to say what stories and books “matter.” Books with a Newbery Medal are likely to be talked about. Right now the conversation coming from the books chosen for Newbery’s top prize has largely silenced Black girls and their present realities. Let’s hope this does not continue to be the case for the award’s next hundred years.

From the May/June 2022 special issue of The Horn Book Magazine: The Newbery Centennial.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!